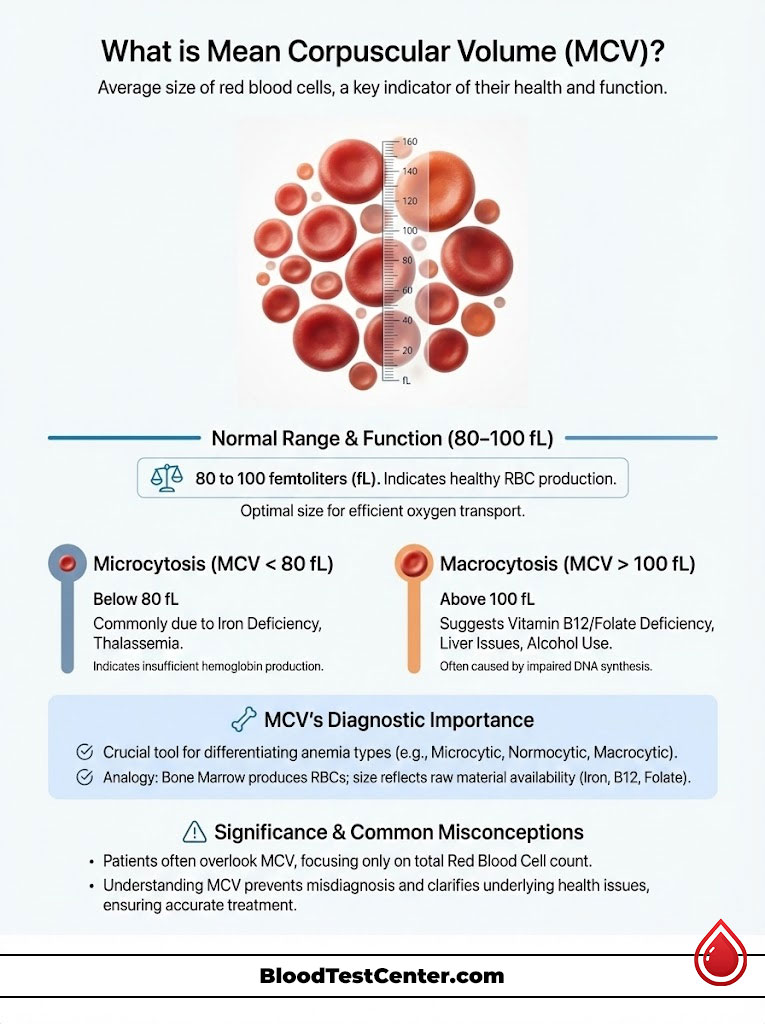

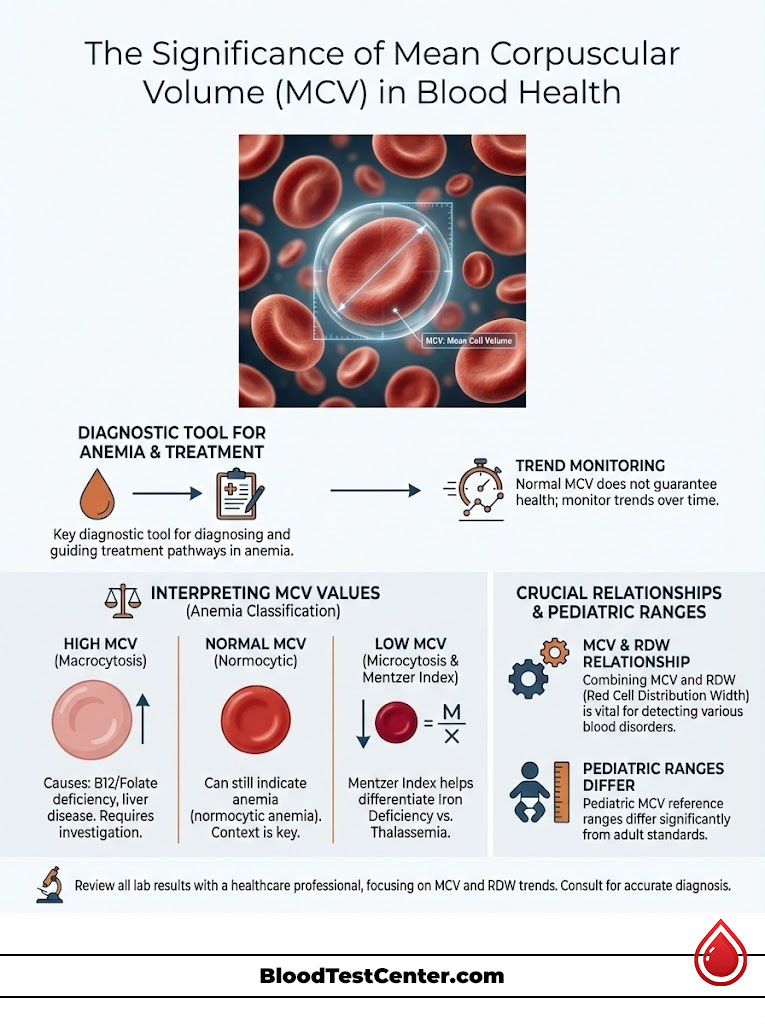

Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) is a vital measurement in a Complete Blood Count (CBC). It determines the average physical size of your red blood cells. It acts as the primary classification tool for anemia types. A normal range is typically 80 to 100 femtoliters (fL).

Table of Contents

Values below 80 fL indicate microcytosis. This is often caused by iron deficiency or thalassemia. Values above 100 fL indicate macrocytosis. This suggests Vitamin B12 deficiency, liver issues, or alcohol use. It tells doctors why you are anemic, not just if you are.

You sit in the doctor’s office. The report in your hand shows low hemoglobin. You naturally ask, “Am I anemic?” The answer is likely yes. However, as a hematology specialist, my first question isn’t about the hemoglobin level. It’s about the size of the cells. The Significance of Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) lies in its ability to act as a diagnostic compass. It points us toward the root cause of the problem rather than just highlighting the symptom.

Think of your bone marrow as a manufacturing plant. It produces millions of products (red blood cells) every single second. If the factory runs out of raw materials like iron, the products come out small and frail. If the machinery (DNA synthesis) malfunctions due to a lack of vitamins, the products come out large and clunky. The MCV blood test measures the physical volume of these cells. It gives us a direct look inside that factory.

Here is the deal. Most patients ignore this number. They focus solely on the red blood cell count. This is a mistake. Understanding your MCV can prevent years of misdiagnosis. It can distinguish between a simple dietary lack and a genetic disorder. This article goes far beyond the basic definition. We will examine the physiological nuances of microcytosis and macrocytosis. We will explore the critical relationship between MCV and RDW. Finally, we will discuss why a “normal” MCV doesn’t always mean you are healthy.

Key Hematology Statistics

- 120 Days: The average lifespan of a red blood cell. Your MCV reflects your health over the last 3 to 4 months.

- 30% of the World: The estimated portion of the global population affected by anemia. It is primarily Iron Deficiency (Microcytic).

- 80-100 fL: The standard reference range for MCV in healthy adults.

- >115 fL: An MCV level highly suggestive of Megaloblastic Anemia (B12/Folate deficiency) rather than just alcohol use.

- Mentzer Index < 13: A calculated value (MCV divided by RBC) that strongly suggests Thalassemia Trait over Iron Deficiency.

- 2.5 Billion: The number of people globally who carry a gene for hemoglobin disorders like Thalassemia.

- 1 in 5: The number of women of childbearing age who have iron deficiency anemia.

The Physiology of the Erythrocyte: Understanding the “Femtoliter”

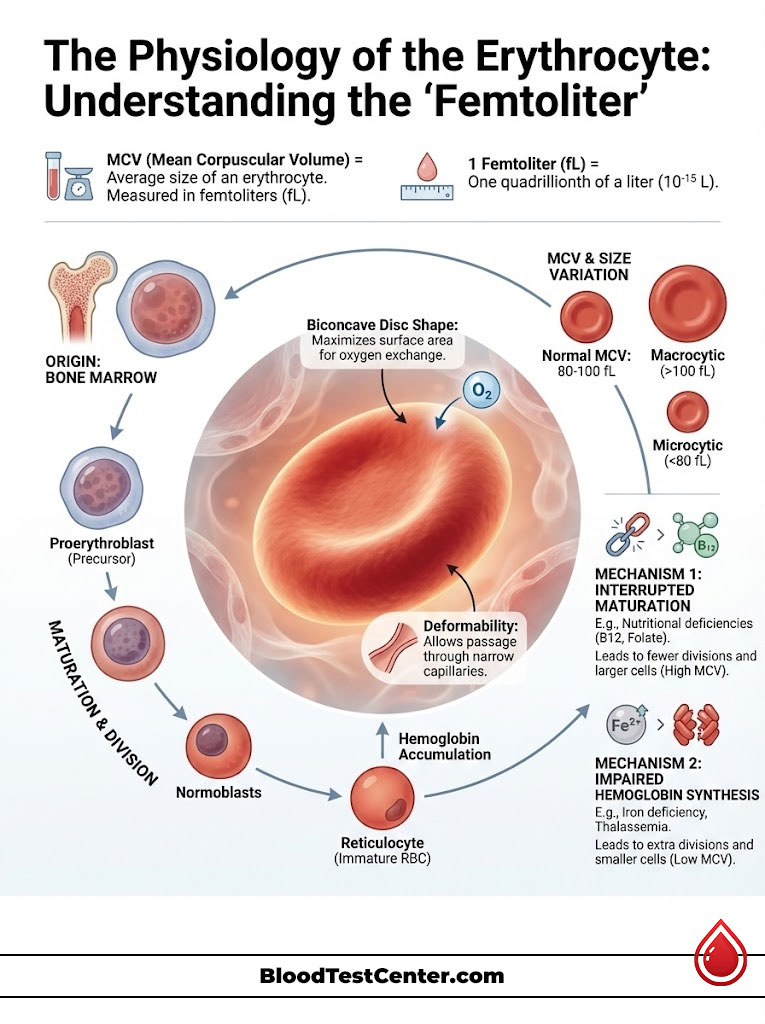

To understand the MCV levels on your lab report, you must first understand the unit of measurement. MCV is measured in femtoliters (fL). One femtoliter is one quadrillionth of a liter. It is unfathomably small. Yet this tiny variance in volume dictates how well your blood carries oxygen.

Red blood cells are also known as erythrocytes. They begin their journey in the bone marrow as large stem cells called proerythroblasts. As they mature, they undergo a rigorous process of division. They also accumulate hemoglobin. In a healthy body, the nucleus is ejected near the end of the process. The cell shrinks to a compact, biconcave disc. This disc is roughly 80 to 100 fL in size.

This shape is not accidental. It is perfect for squeezing through the tiniest capillaries in your eyes and fingertips. These capillaries are often smaller than the cell itself. The cell must fold to pass through. If the volume is too large, it gets stuck. If it is too small, it carries insufficient oxygen.

The Mechanism of Size Variation

The MCV significance becomes clear when this maturation process is interrupted. There are two main mechanisms at play here.

- Cytoplasmic Maturation Defects (Iron constraints): The cell needs hemoglobin to fill its cytoplasm. If iron is missing, hemoglobin production stalls. The cell keeps dividing in a desperate attempt to maintain concentration. This results in tiny, pale cells (Microcytic).

- Nuclear Maturation Defects (DNA constraints): The nucleus requires Vitamin B12 and Folate to synthesize DNA. If these are missing, the nucleus cannot mature or divide. However, the cytoplasm continues to grow. The cell grows larger and larger. It waits for a division signal that never comes. This results in giant cells (Macrocytic).

Interpreting the Numbers: Reference Ranges and Nuances

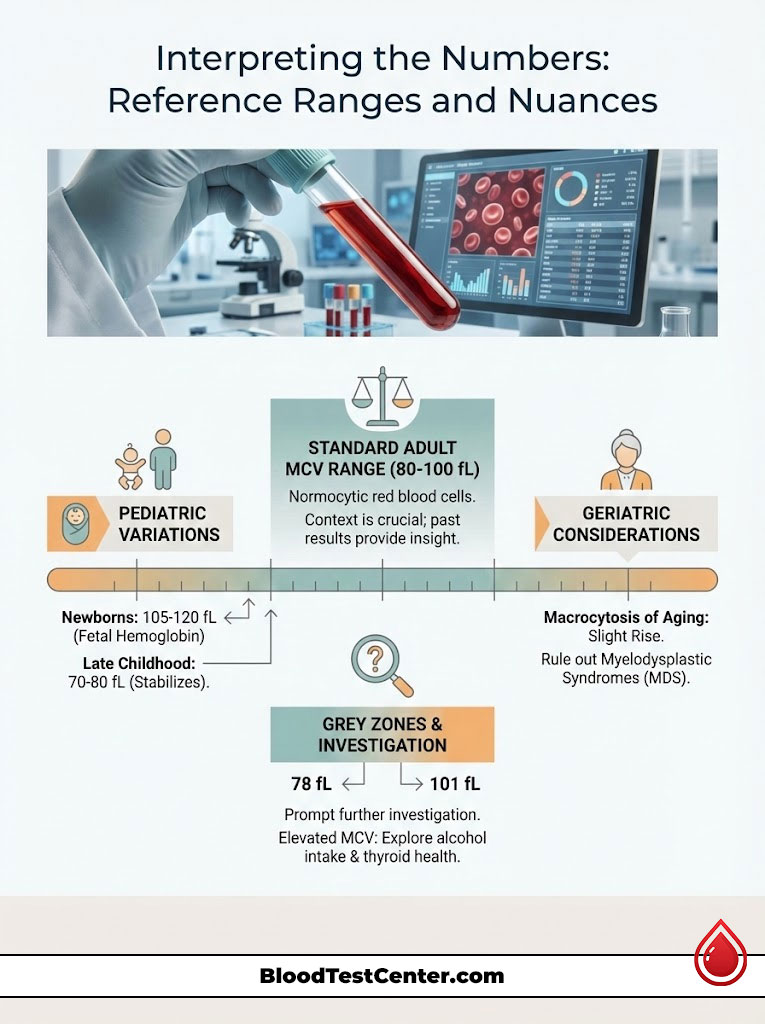

Laboratory cutoffs vary slightly. However, the American Society of Hematology and most major reference labs use the 80-100 fL standard for adults. In clinical practice, we treat these numbers with nuance. We do not treat the patient like a textbook.

Standard Adult Ranges

The “safe zone” is 80 to 100 fL. Within this range, we classify the red blood cells as Normocytic. However, context is key. A value of 81 fL is technically normal. But it might be trending downward for a patient whose baseline is usually 95 fL. This downward trend is a clue. It is why looking at previous results is essential.

Pediatric Variations

Children are not just small adults. Their biology differs significantly. A newborn baby has a naturally high MCV. It is often 105 to 120 fL. This is because fetal hemoglobin is structurally different. It is larger. This is physiologic macrocytosis. It is not a cause for alarm. By late childhood, the MCV drops. It hits the lower end of the adult range (70-80 fL). It stabilizes in the teen years.

The “Grey Zone” Dilemma

Values like 78 fL or 101 fL fall into a diagnostic grey zone. An MCV of 101 fL usually doesn’t trigger a bone marrow biopsy. But it does trigger a conversation. We ask about alcohol intake. We check thyroid health. Similarly, a 79 fL might not be full-blown anemia. But it suggests your iron stores are being depleted. We call this “latent” deficiency.

Expert Insight: The Aging Erythrocyte

In geriatric populations (adults over 65), we often see a slight rise in MCV. This is unexplained by diet. If the patient has an MCV of 102 fL with no anemia and normal B12 levels, we take note. This is sometimes colloquially called “macrocytosis of aging.” However, we must be careful. We must first rule out Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS). MDS is a pre-leukemic condition common in the elderly.

Microcytic Anemia: When Cells Are Too Small (<80 fL)

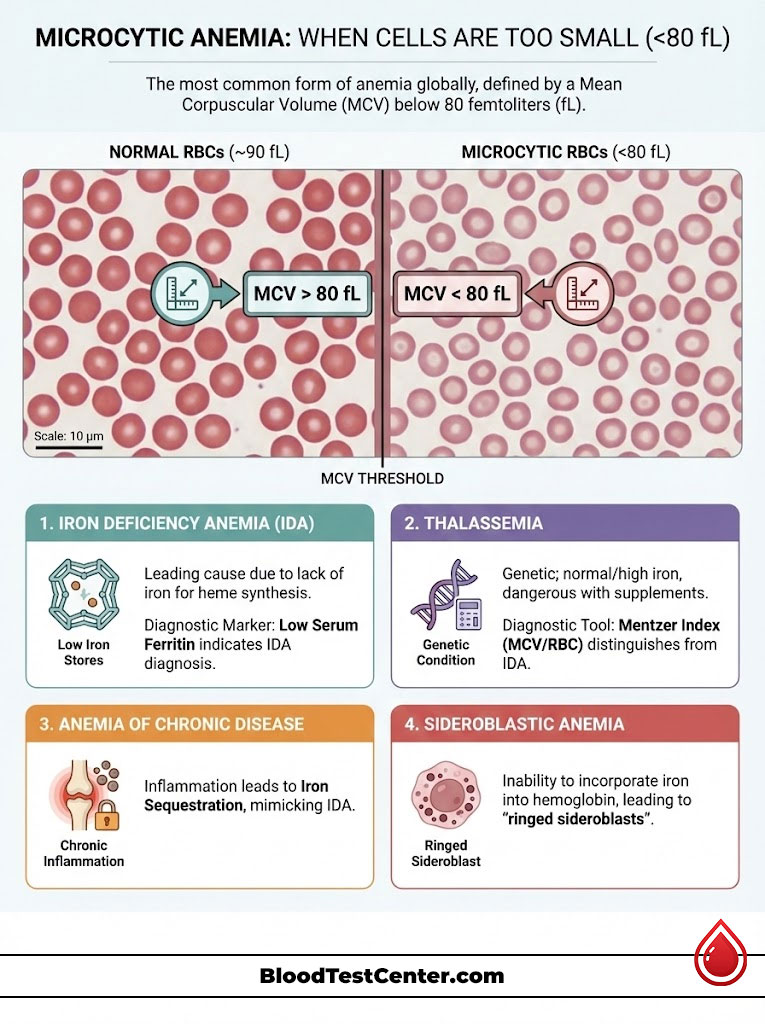

When the MCV blood test returns a value below 80 fL, we diagnose Microcytic anemia. This is the most common form of anemia globally. The core concept here is a “filling defect.” The body is building the cell’s casing. But it lacks the ingredients to fill it.

Cause 1: Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA)

This is the leading cause of a low MCV. Without iron, the body cannot synthesize heme. The cells become small and pale (hypochromic). In the United States, this is frequently caused by chronic blood loss. In women, this is often heavy menstruation. In men or post-menopausal women, it is often GI bleeding. Malabsorption from Celiac disease or gastric bypass is another culprit.

Diagnostic Marker: We look for low Serum Ferritin. Ferritin is the storage protein for iron. If Ferritin is low, the diagnosis is confirmed. It is simple and effective.

Cause 2: Thalassemia (Alpha and Beta)

Thalassemia is a genetic condition. The body produces defective globin chains. Unlike iron deficiency, the iron levels in these patients are often normal or high. This is a critical distinction. Giving iron supplements to a Thalassemia patient can be dangerous. It can lead to iron overload (hemochromatosis). This damages the liver and heart.

The Mentzer Index: We use math to distinguish between Iron Deficiency and Thalassemia without expensive DNA testing. We use the Mentzer Index. You divide the MCV by the Red Blood Cell count (RBC).

Equation: MCV / RBC

If the result is less than 13, it suggests Thalassemia. The marrow is making many tiny cells. If it is greater than 13, it suggests Iron Deficiency. The marrow is making fewer cells due to lack of materials.

Cause 3: Anemia of Chronic Disease (Late Stage)

Chronic inflammation confuses the body. Conditions like Rheumatoid Arthritis, Lupus, or Cancer release a protein called Hepcidin. Hepcidin locks iron away in storage cells. It prevents the bone marrow from using it. Initially, this causes Normocytic anemia. But over time, the cells become starved of iron. They become microcytic. This mimics Iron Deficiency, but Ferritin levels will be normal or high.

Cause 4: Sideroblastic Anemia

This is a rare condition. The body has iron, but it cannot incorporate it into the hemoglobin molecule. The iron accumulates in the mitochondria of the cell. This forms a ring around the nucleus. We call these “ringed sideroblasts.” This can be genetic. It can also be acquired through toxins like alcohol or lead poisoning. Lead poisoning specifically inhibits enzymes needed for heme synthesis.

Macrocytic Anemia: When Cells Are Too Large (>100 fL)

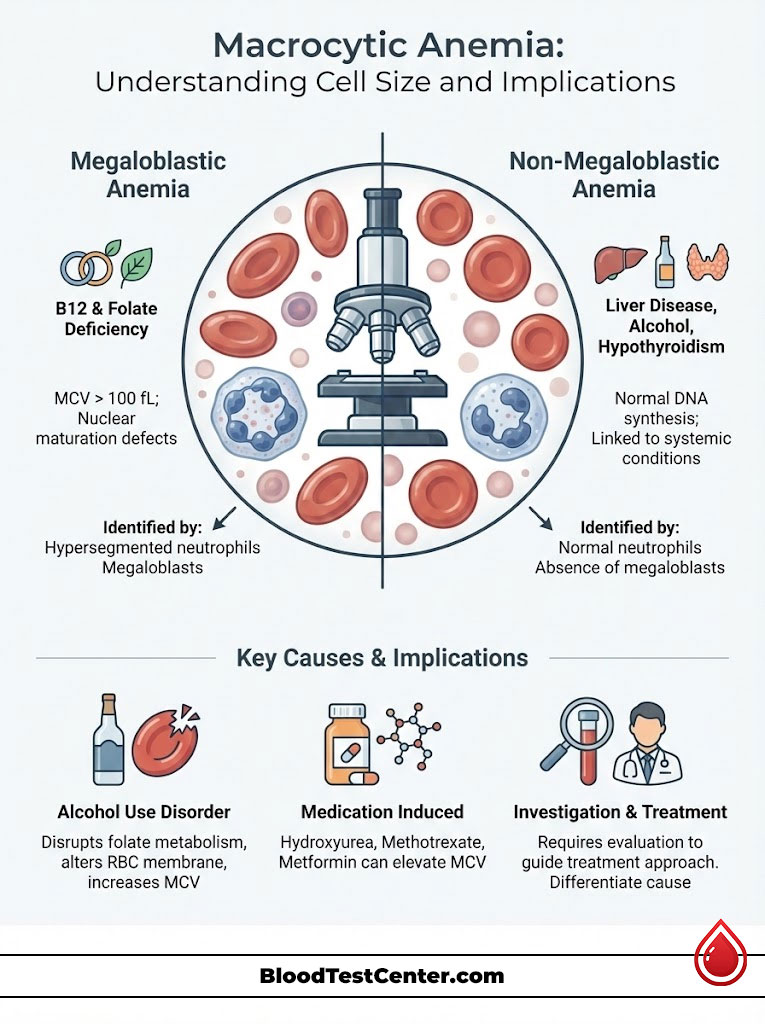

Macrocytic anemia occurs when the MCV exceeds 100 fL. This is a defect of nuclear maturation. The cytoplasm (the jelly of the cell) grows normally. But the nucleus lags behind. This results in a giant cell. This is a serious finding. It requires immediate investigation.

Megaloblastic vs. Non-Megaloblastic

We divide macrocytosis into two categories based on the mechanism. This distinction changes the treatment plan entirely.

1. Megaloblastic Anemia:

This is caused by a failure of DNA synthesis. The primary culprits are Vitamin B12 deficiency and Folate deficiency. On a peripheral blood smear, we see hypersegmented neutrophils. These are white blood cells with too many lobes. The bone marrow is packed with large, immature cells called megaloblasts.

2. Non-Megaloblastic Anemia:

The DNA synthesis is fine here. The cell membrane is expanding due to lipid issues. This is seen in liver disease and alcohol use disorder. It is also seen in hypothyroidism. The cells are large, but the neutrophils are normal.

Alcohol Use Disorder

Alcohol is toxic to the bone marrow. It interferes with folate metabolism. It also alters the cholesterol-to-phospholipid ratio in the red blood cell membrane. This causes the membrane to become redundant and baggy. This increases the volume. An elevated MCV is often used as a marker for long-term alcohol consumption. It appears even before liver enzymes (AST/ALT) rise.

Medication Induced Macrocytosis

Many modern drugs interfere with DNA synthesis. This is sometimes by design and sometimes a side effect.

Hydroxyurea: This is used for Sickle Cell and cancer. It almost always causes high MCV.

Methotrexate: This is used for Rheumatoid Arthritis. It is a folate antagonist.

Metformin: This is a common diabetes drug. It can block B12 absorption in the gut.

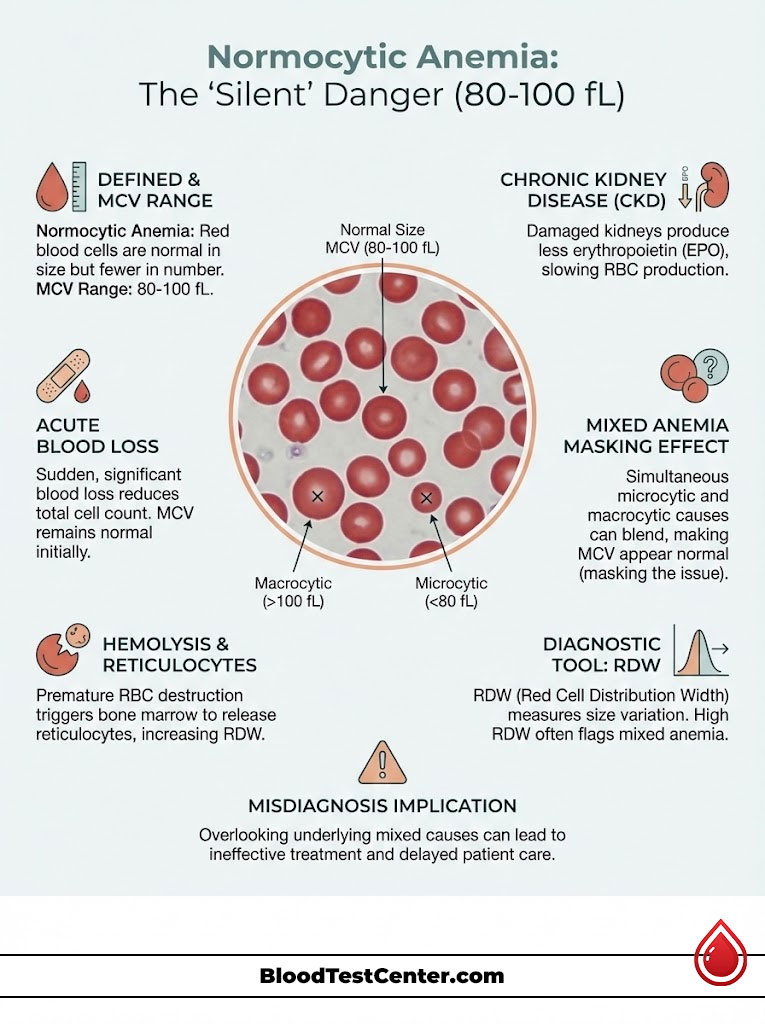

Normocytic Anemia: The “Silent” Danger (80-100 fL)

Normocytic anemia is perhaps the most tricky diagnosis. The MCV is normal (80-100 fL). Yet the hemoglobin is low. This implies the factory (marrow) is working fine. But the product is being lost or destroyed after it leaves the gate.

Acute Blood Loss

If you suffer a traumatic injury, you lose whole blood. You lose plasma and cells together. The remaining cells are normal in size. There are just fewer of them. The bone marrow hasn’t had time to react yet. It takes time for new, smaller or larger cells to appear.

Hemolysis

In hemolytic anemia, the immune system attacks red blood cells. It destroys them. The cells are broken down faster than they can be replaced. The remaining cells are often normal in size. However, the reticulocyte count (baby red blood cells) will be very high. The marrow tries to compensate. Reticulocytes are slightly larger than mature cells. Severe hemolysis can sometimes cause a falsely high MCV.

Chronic Kidney Disease

The kidneys are not just filters. They produce a hormone called Erythropoietin (EPO). EPO tells the bone marrow to make blood. When kidneys fail, EPO levels drop. The marrow makes fewer cells. But the cells it does make are perfectly normal in size. This is a classic normocytic anemia.

The “Mixed” Anemia Masking Effect

This is a scenario that fools many general practitioners. Consider a patient with severe Crohn’s disease. They might have Iron deficiency (which pulls MCV down). They might also have B12 deficiency (which pulls MCV up).

Result: The MCV averages out to 90 fL. This looks perfectly normal.

However, the RDW (Red Cell Distribution Width) will be sky-high. The patient has both tiny and huge cells floating around. The average is misleading. This leads us to our next critical section.

The Clinical Power Couple: MCV and RDW

A Hematologist never looks at MCV levels in isolation. We always pair it with the RDW (Red Cell Distribution Width). While MCV tells us the average size, RDW tells us the variation in size. This is technically called anisocytosis.

If your MCV is normal but your RDW is high, it is a red flag. It suggests a mixed population of cells. It could also mean the very early stages of a nutritional deficiency. The average hasn’t shifted yet, but the new cells are changing size.

Comparison Table: The MCV & RDW Diagnostic Matrix

| MCV Level | RDW Level | Most Likely Diagnosis | Follow-Up Test Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (<80 fL) | High | Iron Deficiency Anemia | Serum Ferritin, Iron Saturation |

| Low (<80 fL) | Normal | Thalassemia Minor / Trait | Hemoglobin Electrophoresis |

| High (>100 fL) | High | B12 or Folate Deficiency | Serum B12, Folate, Homocysteine |

| High (>100 fL) | Normal | Alcoholism, Liver Disease | Liver Function Tests (ALT/AST) |

| Normal (80-100) | High | Early deficiency or Mixed Anemia | Peripheral Blood Smear |

| Normal (80-100) | Normal | Acute Blood Loss, Renal Failure | Reticulocyte Count, Creatinine |

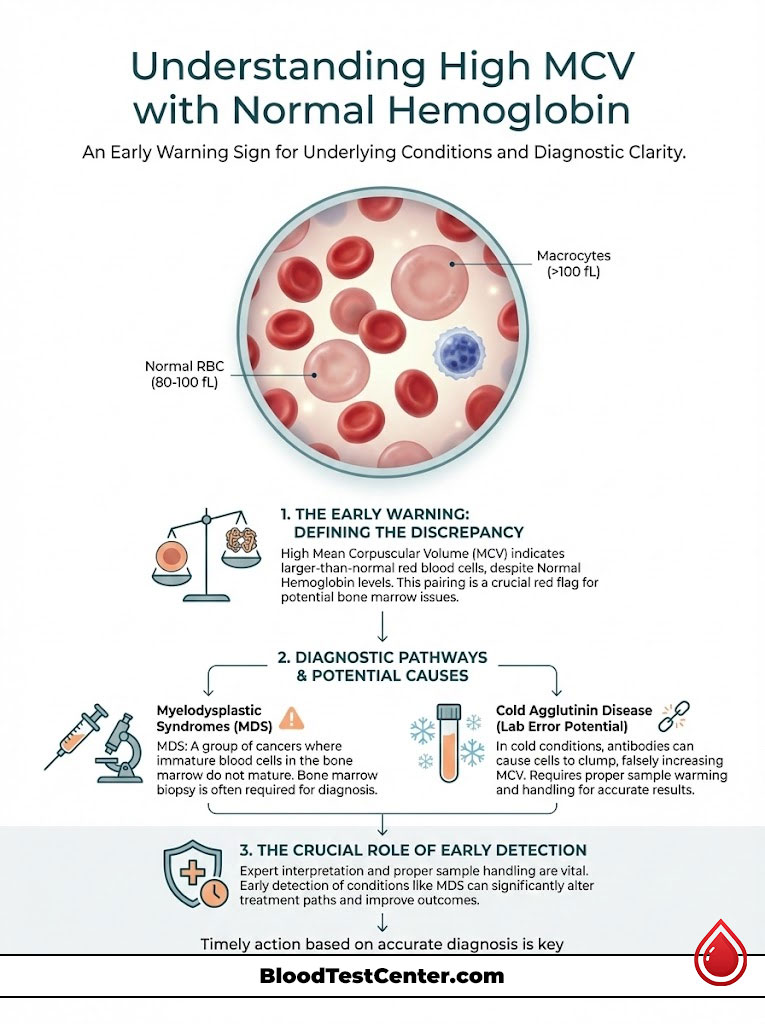

Beyond Anemia: High MCV with Normal Hemoglobin

One of the most confusing scenarios for patients is receiving a lab report that shows a high MCV but normal hemoglobin. You aren’t technically anemic. So why is the MCV flagged?

This is often an “early warning” system. The MCV significance here is predictive. Your body is struggling to maintain normal blood counts. The stress is showing in the size of the cells before the total count drops. It is like an engine overheating before the car actually stops.

In Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS), unexplained macrocytosis is often the very first sign. MDS is a group of cancers where blood cells in the bone marrow do not mature. If an older adult has a persistently high MCV with no nutritional deficiency, we must consider a bone marrow biopsy. We need to rule out MDS. Catching this early can significantly alter the treatment path.

Cold Agglutinin Disease: A False Alarm

Sometimes, the high MCV is a lab error. In a condition called Cold Agglutinin Disease, the patient’s blood clumps together when it cools down in the test tube. The machine counts a clump of three cells as one giant cell. This gives a falsely high MCV. If we warm the blood sample and run it again, the MCV returns to normal. This is why expert interpretation is vital.

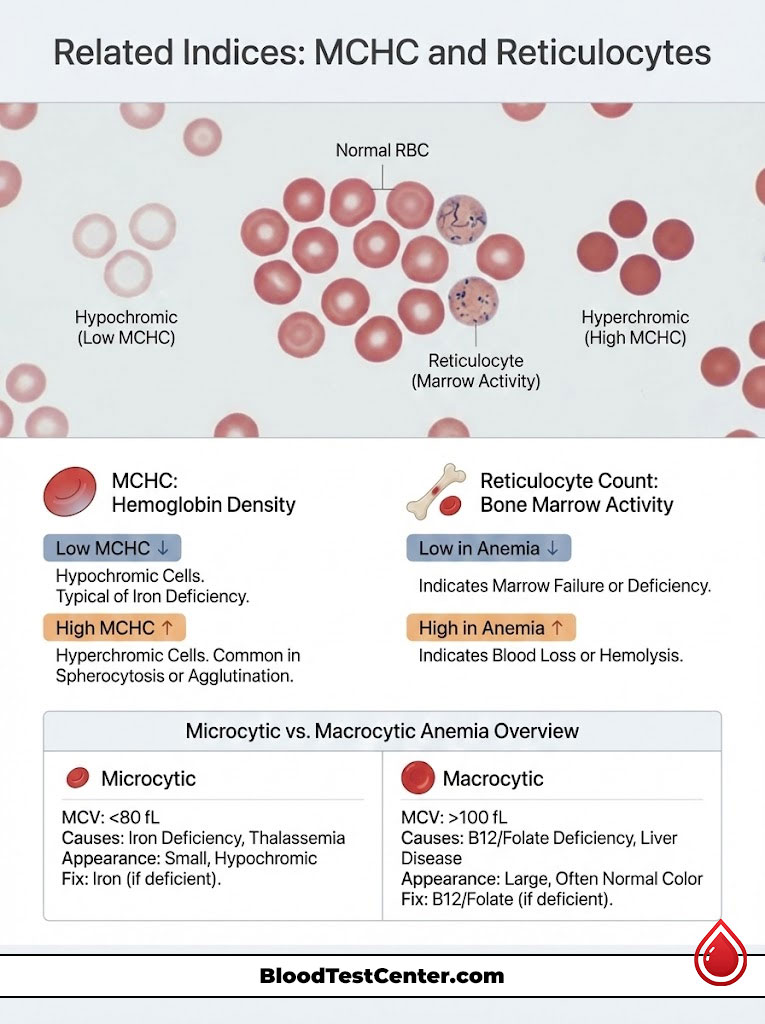

Related Indices: MCHC and Reticulocytes

To fully grasp the picture, we must briefly mention the neighbors of MCV on your lab report. They provide the color and the context.

MCHC (Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration):

While MCV measures size, MCHC measures color (density of hemoglobin).

Low MCHC: Hypochromic (pale cells). This is typical of Iron deficiency.

High MCHC: Hyperchromic. This is typical of Spherocytosis (a membrane defect) or agglutination.

The Reticulocyte Count:

This measures how hard your bone marrow is working. It counts the baby red blood cells.

If you are anemic and your reticulocyte count is low, it means the factory has shut down. This is due to deficiency or failure.

If you are anemic and your reticulocyte count is high, the factory is working overtime. But the cells are being lost. This suggests bleeding or hemolysis.

Comparison Table: Microcytic vs. Macrocytic Anemia Overview

| Feature | Microcytic Anemia | Macrocytic Anemia |

|---|---|---|

| MCV Range | < 80 fL | > 100 fL |

| Primary Deficiencies | Iron, Copper, Pyridoxine (B6) | Vitamin B12, Folate (B9) |

| Genetic Causes | Thalassemia, Sideroblastic Anemia | Rare enzyme disorders |

| Systemic Causes | Chronic Inflammation, Lead Poisoning | Liver Disease, Hypothyroidism, Alcohol |

| Cell Appearance | Small, Pale (Hypochromic) | Large, Oval-shaped (Macro-ovalocytes) |

| Dietary Fixes | Red meat, spinach, fortified grains | Leafy greens, eggs, dairy, liver |

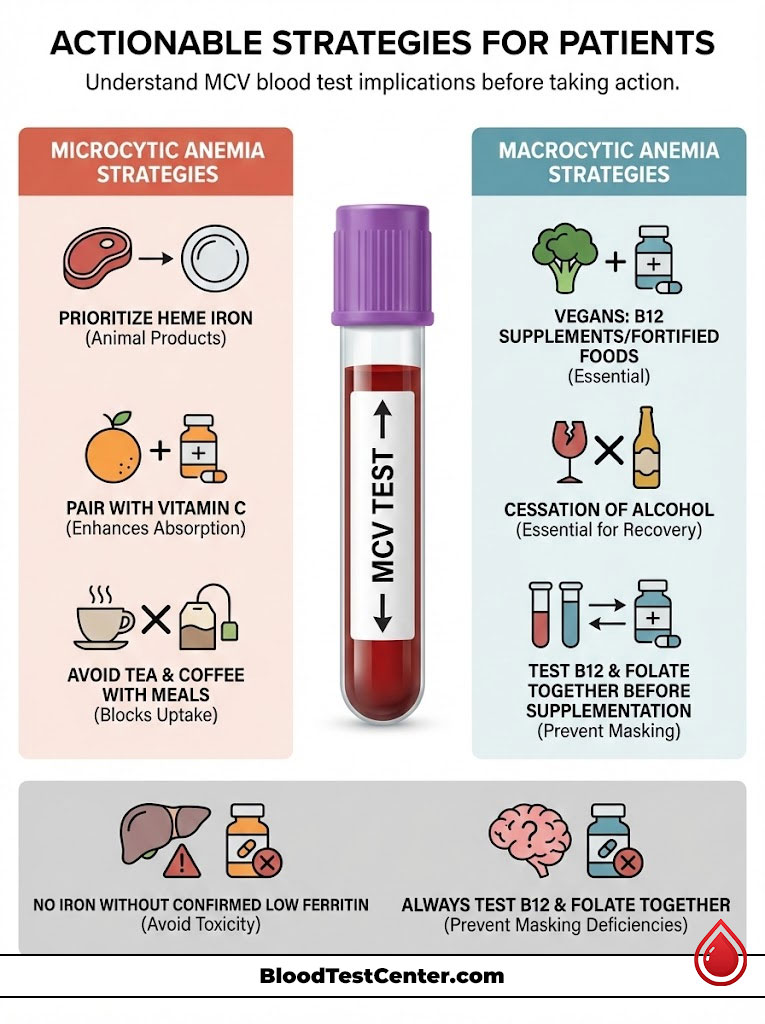

Actionable Strategies for Patients

Understanding your MCV blood test is the first step. Taking action is the second. However, self-treatment can be risky without a confirmed diagnosis. You must know what you are treating before you start.

Dietary Interventions for Microcytosis

For Microcytic anemia (Iron Deficiency), focus on Heme iron. This is found in animal products. It is absorbed efficiently (15-30%). Non-heme iron is found in spinach and beans. It has a much lower absorption rate (5%).

Pro Tip: Always pair iron-rich foods with Vitamin C. Oranges, peppers, and strawberries boost absorption. Avoid tea and coffee with meals. The tannins in these drinks block iron uptake significantly. Wait at least one hour after eating to drink your tea.

Dietary Interventions for Macrocytosis

For Macrocytic anemia (B12 Deficiency), vegans are at high risk. B12 is found primarily in animal products. Supplementation or fortified nutritional yeast is non-negotiable for strict plant-based diets. For alcohol-induced macrocytosis, cessation of alcohol is the only cure. The MCV will take 3 to 4 months to correct after you stop drinking.

Supplementation Safety and Protocols

Here is a warning I give all my patients. Do not take iron supplements unless you have a confirmed low Ferritin level. Iron is not water-soluble. The body cannot easily excrete excess iron. Taking it unnecessarily can lead to Hemochromatosis. This is iron overload. It damages the liver, pancreas, and heart.

Similarly, be careful with Folate. Taking Folate (B9) can correct the anemia caused by B12 deficiency. But it will not correct the nerve damage. This “masks” the B12 deficiency. It allows neurological damage to progress unchecked. Always test B12 and Folate together before supplementing.

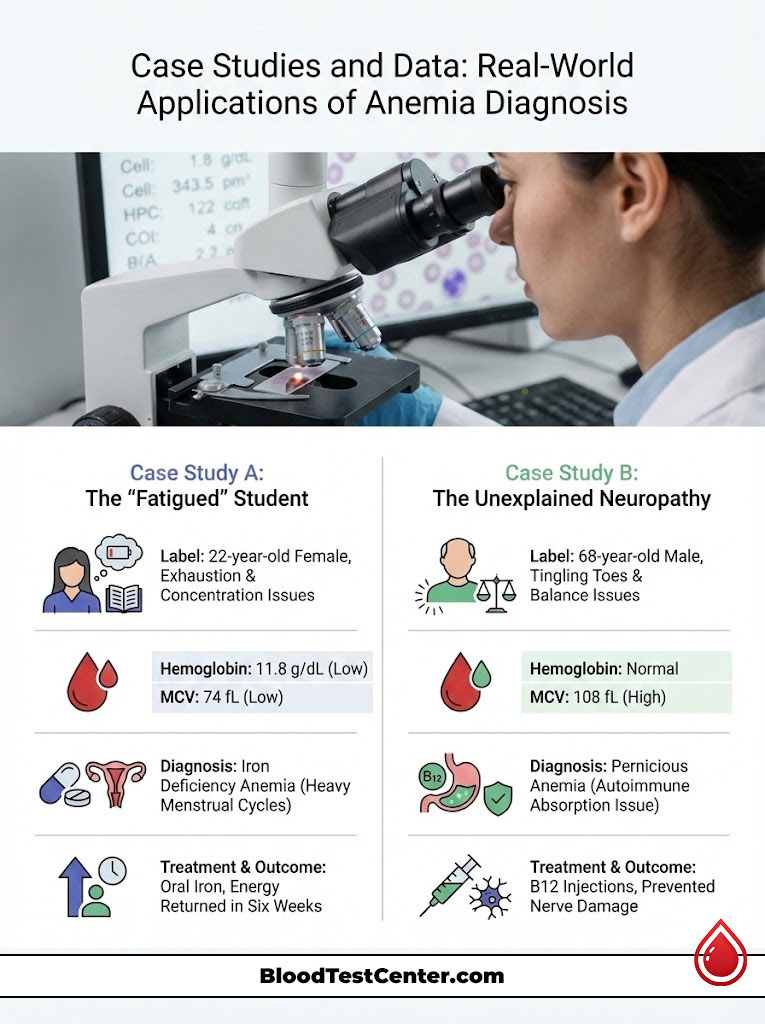

Case Studies and Data

To illustrate the real-world application of these concepts, let’s look at two common scenarios. These are composites of cases seen in clinical practice.

Case Study A: The “Fatigued” Student

A 22-year-old female presented with exhaustion. She had difficulty concentrating in class. Her hemoglobin was borderline (11.8 g/dL). Her previous doctor dismissed it as stress or “normal for a woman.” However, the low MCV was glaring at 74 fL. The low MCV prompted a Ferritin test. It came back at 8 ng/mL. This is a severe deficiency. She had Iron Deficiency Anemia caused by heavy menstrual cycles. With oral iron therapy, her energy returned in six weeks. Her MCV normalized in four months.

Case Study B: The Unexplained Neuropathy

A 68-year-old male complained of tingling in his toes. His balance was off. His hemoglobin was normal. But his MCV was 108 fL. He drank alcohol socially but not excessively. The high MCV led to B12 testing. It revealed Pernicious Anemia. This is an autoimmune condition where the gut cannot absorb B12. No amount of steak would fix this. He required B12 injections. This stopped the nerve damage progression. If we had ignored the MCV because the hemoglobin was normal, he might have lost the ability to walk.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The Significance of Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) cannot be overstated. It is the lens through which we view the quality of your blood. It transforms a generic diagnosis of “anemia” into a specific, actionable path toward treatment. It saves time. It saves money on unnecessary tests. Most importantly, it leads to the correct cure.

Remember that a “Normal” MCV does not always guarantee health. This is especially true in the presence of mixed deficiencies or chronic disease. The most powerful tool you have is the trend line. Look at how your numbers change over months and years. A slow drift is just as important as a sudden spike.

Always request a copy of your labs. Look at the MCV. Check the RDW. Ask your doctor specifically about these indices. Do not settle for “everything looks fine.” Your health is in the details. Knowledge of these numbers empowers you to advocate for your own well-being.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a high MCV level on a blood test indicate?

A high Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) above 100 fL, known as macrocytosis, indicates that your red blood cells are larger than normal. This is typically caused by DNA maturation defects often linked to Vitamin B12 or folate deficiencies, liver disease, or chronic alcohol consumption. In older patients, it may also serve as an early clinical marker for Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS).

Can I have a normal MCV and still be anemic?

Yes, this is classified as normocytic anemia, where the cells are the correct size (80-100 fL) but the total hemoglobin is low. This often occurs in the setting of acute blood loss, chronic kidney disease, or systemic inflammation. It can also happen in “mixed” anemias where a concurrent iron deficiency and B12 deficiency average out the cell volume to a deceptive normal range.

How does the Mentzer Index help distinguish between iron deficiency and thalassemia?

The Mentzer Index is a calculated ratio of MCV divided by the red blood cell count (RBC). A result lower than 13 suggests Thalassemia, as the bone marrow is producing many tiny cells, whereas a result higher than 13 points to iron deficiency anemia. This tool is vital for clinicians to avoid the dangerous mistake of prescribing iron supplements to Thalassemia patients.

Why is the relationship between MCV and RDW critical for diagnosis?

While MCV tells us the average size of red blood cells, the Red Cell Distribution Width (RDW) measures the variation in that size, known as anisocytosis. A normal MCV paired with a high RDW is a significant red flag for early nutritional deficiency or a mixed-cause anemia. Hematologists use this pairing to detect evolving blood disorders before the average cell volume shifts out of range.

What are the most common causes of microcytic anemia?

Microcytic anemia, defined by an MCV below 80 fL, is most frequently caused by iron deficiency due to chronic blood loss or poor absorption. Other causes include genetic hemoglobinopathies like Thalassemia, lead poisoning, and late-stage anemia of chronic disease. These conditions share a common mechanism where the lack of hemoglobin prevents the red blood cell from reaching its full physiological volume.

Does alcohol consumption affect red blood cell size?

Chronic alcohol use is a common cause of non-megaloblastic macrocytosis, frequently raising the MCV above 100 fL. Alcohol acts as a direct toxin to the bone marrow and interferes with folate metabolism, while also altering the lipid composition of the erythrocyte membrane. This elevation often persists for three to four months after cessation of alcohol, reflecting the 120-day lifespan of the red blood cell.

What is the significance of a high MCV with a normal hemoglobin level?

A high MCV without anemia is often an “early warning” that the bone marrow is under stress or lacking essential nutrients. It can precede the drop in hemoglobin by months or even years, especially in cases of B12 deficiency or early-stage myelodysplasia. This finding warrants further investigation into thyroid function, liver health, and vitamin levels to prevent future hematological decline.

How do pediatric MCV reference ranges differ from adult standards?

Pediatric MCV ranges are highly age-dependent and differ significantly from the adult 80-100 fL standard. Newborns naturally have very high MCV levels (often 105-120 fL) due to the presence of fetal hemoglobin, while older children typically have lower MCV values (70-80 fL) compared to adults. It is essential to use age-specific reference intervals to avoid misdiagnosing a healthy child with a blood disorder.

Why should I avoid taking folate supplements before testing my B12 levels?

Folate supplementation can “mask” a B12 deficiency by correcting the macrocytic anemia and normalizing the MCV, but it does not treat the underlying neurological damage. This can allow permanent nerve damage and subacute combined degeneration of the spinal cord to progress undetected. We always recommend testing both B12 and folate levels simultaneously before beginning any high-dose supplementation.

What role does the reticulocyte count play in interpreting MCV?

The reticulocyte count measures the production of new, “baby” red blood cells, which are naturally larger than mature cells. If you have a high MCV and a very high reticulocyte count, it may indicate that the marrow is working overtime to replace cells lost to bleeding or hemolysis. Conversely, a low reticulocyte count with an abnormal MCV suggests a production failure at the bone marrow level.

Can certain medications change my MCV levels?

Several common medications can induce macrocytosis by interfering with DNA synthesis or nutrient absorption. Hydroxyurea (used for Sickle Cell) and Methotrexate (used for autoimmune diseases) frequently cause an elevated MCV. Additionally, the diabetes medication Metformin can lead to B12 malabsorption, eventually resulting in a rise in cell volume over time.

What is the difference between megaloblastic and non-megaloblastic macrocytosis?

Megaloblastic macrocytosis is caused by impaired DNA synthesis, usually from B12 or folate deficiency, and is characterized by “megaloblasts” in the marrow and hypersegmented neutrophils. Non-megaloblastic macrocytosis involves a different mechanism, such as membrane changes in liver disease or hypothyroidism, where DNA synthesis remains intact. Distinguishing between these two is vital for determining whether a patient needs vitamins or systemic disease management.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The Significance of Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) and other lab indices should always be interpreted by a qualified healthcare professional in the context of your full clinical history. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

References

- American Society of Hematology (ASH) – hematology.org – Comprehensive guidelines on the classification and diagnosis of various types of anemia.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) – nhlbi.nih.gov – Authoritative data on iron deficiency anemia and global blood health statistics.

- Mayo Clinic Proceedings – mayoclinic.org – Clinical reviews on the interpretation of macrocytosis and its relationship to B12/Folate levels.

- The Lancet Haematology – thelancet.com – Research studies regarding the global burden of anemia and the diagnostic utility of red cell indices.

- Merck Manual Professional Version – merckmanuals.com – Detailed physiological breakdown of microcytic, macrocytic, and normocytic anemias.

- World Health Organization (WHO) – who.int – Global nutritional deficiency reports and the prevalence of hemoglobin disorders like Thalassemia.

- Journal of Clinical Pathology – jcp.bmj.com – Scientific validation of the Mentzer Index and RDW in differential diagnosis.