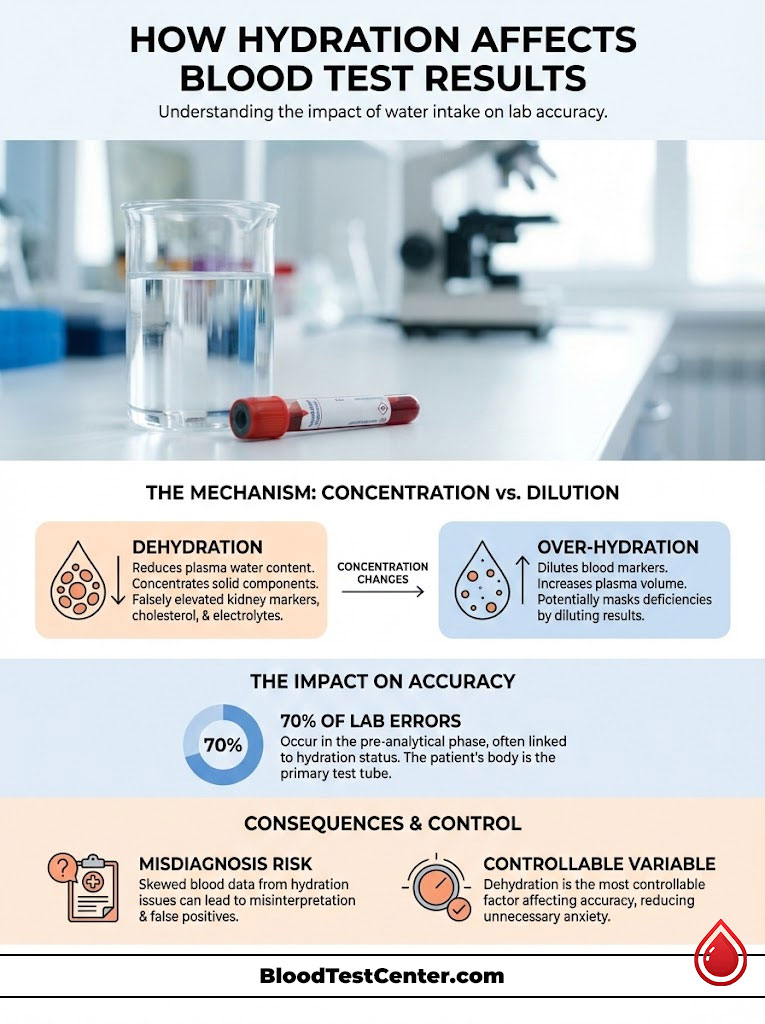

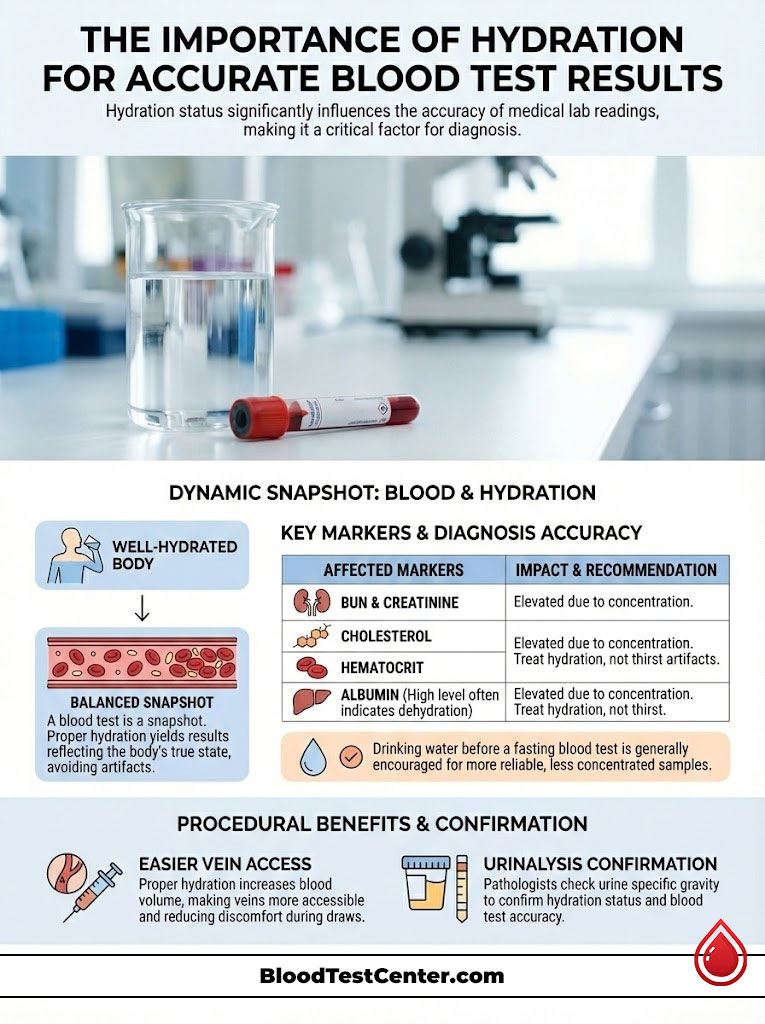

The answer to how do dehydration or hydration status affect blood test results is significant. Dehydration reduces the water content in your plasma. This artificially concentrates solid components like red blood cells and proteins. It leads to false spikes in kidney markers, cholesterol, and electrolytes. Conversely, drinking too much water can dilute these markers and hide deficiencies.

Table of Contents

The American Association for Clinical Chemistry (AACC) reports a startling statistic. Up to 70% of laboratory errors occur in the “pre-analytical” phase. This means the mistake happens before the sample ever reaches our microscopes or analyzers.

In my fifteen years as a clinical pathologist, I have seen countless patients referred to specialists. They are sent for kidney failure or blood disorders they did not actually have. The culprit is rarely a broken machine.

It is almost always the patient’s hydration status. We must understand that the validity of your blood test results relies entirely on the ratio of fluid to solid matter in your veins. When a patient arrives for a draw, their body acts as the primary test tube.

If that test tube is missing its solvent—water—the data we extract becomes skewed. Dehydration is the single most controllable variable for patients. Yet it is the most frequently overlooked.

A lack of fluid does not necessarily change the absolute amount of disease markers in your body. It changes their concentration. This leads to false positives, misdiagnoses, and unnecessary anxiety.

Key Statistics & Data

- 70% of lab errors occur in the pre-analytical phase (patient prep and collection).

- 20:1 is the BUN/Creatinine ratio threshold that typically signals dehydration.

- 5% to 10% variance in Cholesterol levels can occur due to posture and hydration changes.

- 2% loss of body water is sufficient to significantly alter cognitive and physical performance.

- 60 Minutes is the ideal window for drinking water before a blood draw to ensure vein turgor.

- 15% increase in Hematocrit can be observed in severe dehydration cases.

The Physiology of the Blood Draw: Hemoconcentration vs. Hemodilution

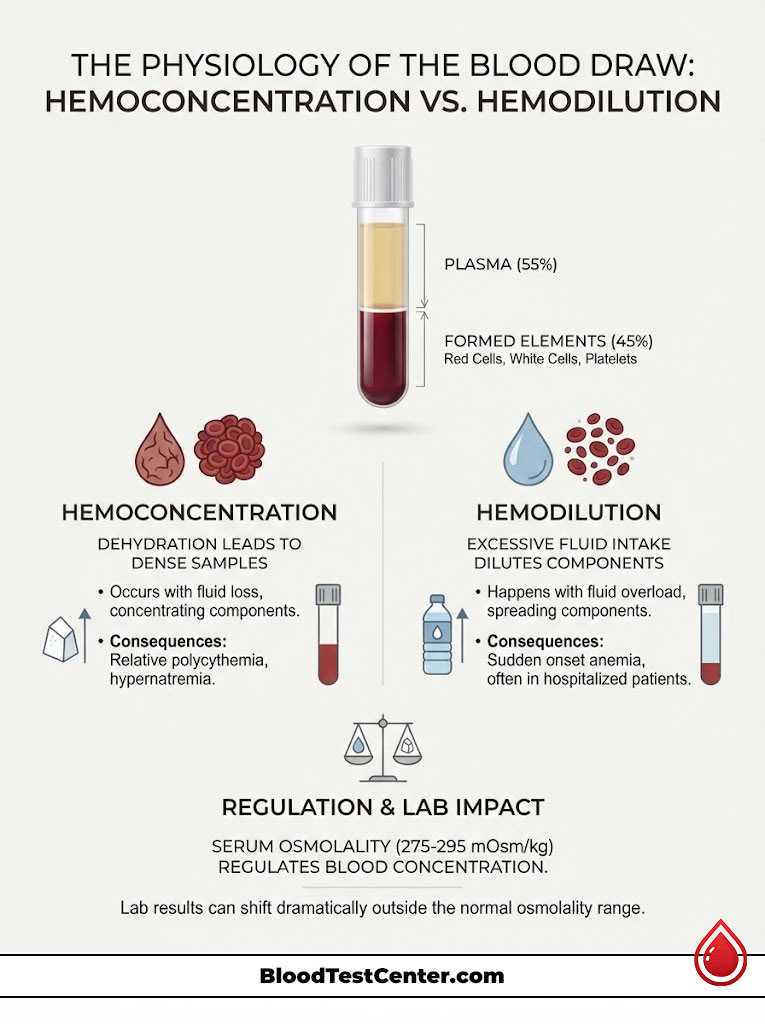

To understand why your lab report might look alarming, we have to look at what blood actually is. It is not a uniform red liquid. It is a suspension.

Blood is roughly composed of 55% plasma (water, proteins, electrolytes) and 45% formed elements. These elements include red cells, white cells, and platelets. Think of your blood like a pot of soup.

If you leave the soup on the stove and half the broth boils away, the remaining soup tastes incredibly salty. Did you add more salt? No. The amount of salt remained constant.

The volume of water decreased. In pathology, we call this hemoconcentration. This is the core mechanism behind many false lab results.

The Mechanism of Hemoconcentration

When you are dehydrated, your blood volume drops. This is technically called hypovolemia. The plasma water exits the vascular space to hydrate your cells.

This leaves the “solids” behind in the veins. When we draw blood in this state, we are pulling a sample that is densely packed with analytes. This pre-analytical variable causes artificial spikes.

We see increases in:

- Red blood cells

- Proteins (Albumin)

- Electrolytes

- Waste products (Urea)

This is technically known as relative polycythemia or relative hypernatremia. The “relative” part is key. It is relative to the water volume, not an absolute increase in production by the body.

The Flip Side: Hemodilution

The opposite error occurs with overhydration. If a patient consumes excessive water or receives IV fluids right before a draw, the plasma volume expands. This dilutes the cellular components.

We often see hospitalized patients with “sudden onset anemia.” This is actually just hemodilution. Their red blood cell count looks low because their veins are flooded with saline.

The body attempts to regulate this through Serum Osmolality. This is a measure of the concentration of chemicals in the blood. A healthy body fights to keep this between 275 and 295 mOsm/kg.

When you fall outside this range due to fluid intake, the lab results shift dramatically. It is a delicate balance. Your lab results hang in this balance.

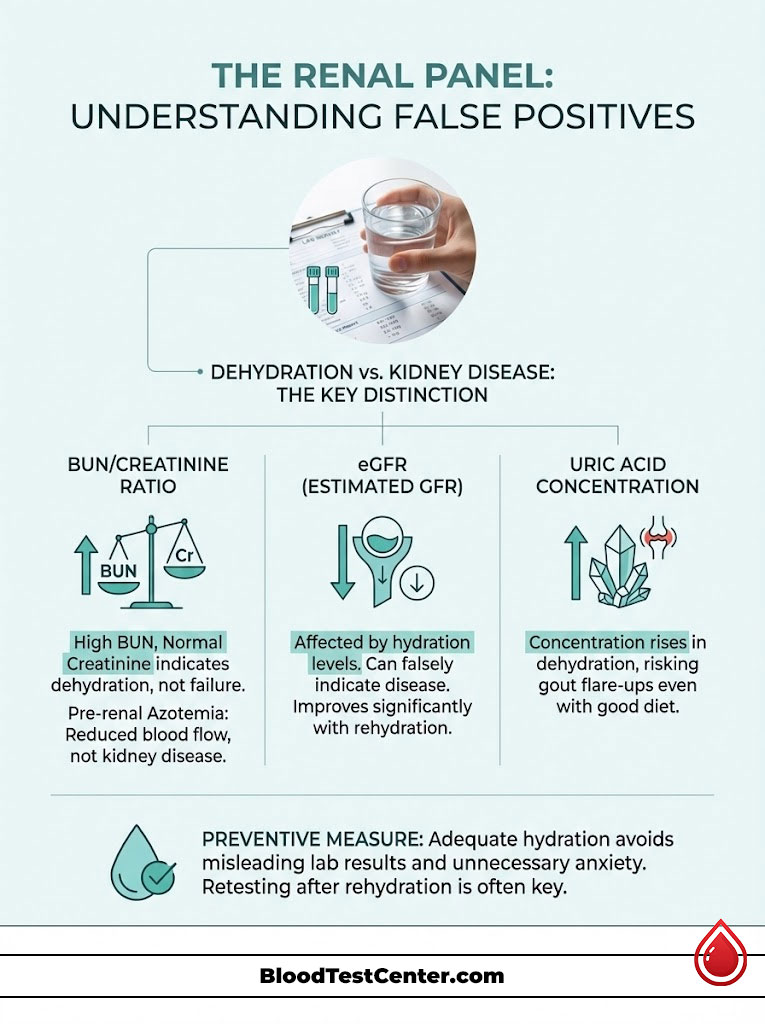

The Renal Panel: The Most Common False Positives

The area where I see the most confusion involves the kidneys. The Basic Metabolic Panel (BMP) or Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP) contains markers. These markers are exquisitely sensitive to flow rate and hydration.

The BUN/Creatinine Ratio

This is the first thing I look at when a clinician asks about kidney failure. Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) is a waste product filtered by the kidneys. However, urea is unique.

The kidneys can reabsorb it back into the blood if fluid flow is slow. When you are dehydrated, your body tries to hold onto water. In doing so, it pulls urea back into the system.

This causes the BUN to skyrocket. Creatinine, on the other hand, is a waste product from muscle breakdown. It is generally filtered out at a steady rate.

It is less affected by water reabsorption. Here is the diagnostic clue. If your BUN is high but your Creatinine is normal, we calculate the ratio.

A BUN/Creatinine ratio greater than 20:1 strongly suggests “Pre-renal Azotemia.” In plain English? You aren’t in kidney failure.

You are just thirsty. The “Pre-renal” term means the problem is before the kidney. It indicates low blood flow due to dehydration, not disease inside the kidney.

eGFR (Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate)

This number estimates how well your kidneys are filtering waste. It is calculated using your Creatinine level, age, and gender. Because dehydration can cause a slight rise in Creatinine, the math changes.

This calculation often results in a lower eGFR. I have seen patients terrified because their eGFR dropped to 55. This places them technically in Stage 3 Kidney Disease.

After rehydrating and retesting a week later, their eGFR returned to >90. This false positive lab result causes unnecessary referrals to nephrologists. It wastes time and money.

Pathologist’s Insight: Uric Acid is another marker that concentrates in dehydrated blood. If you are prone to gout, a simple day of poor fluid intake can concentrate uric acid enough to trigger a crystallization event. This can cause a gout flare even if your diet has been perfect.

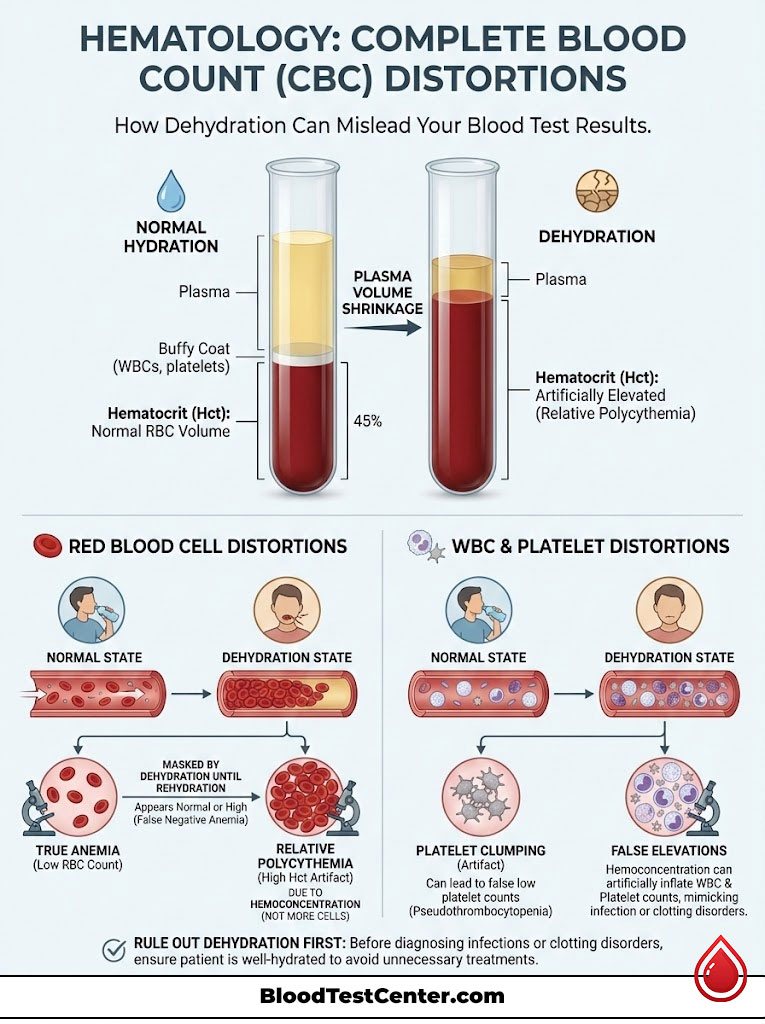

Hematology: Complete Blood Count (CBC) Distortions

The Complete Blood Count (CBC) is the most common blood test ordered in the USA. It counts your red cells, white cells, and platelets. Hydration status acts as a magnifying glass here.

Red Blood Cell Indices

Hematocrit (Hct) measures the volume percentage of red blood cells in the blood. If you are a male, a normal Hct is roughly 40-54%. If you come in severely dehydrated, your plasma volume shrinks.

Your Hematocrit might read 58%. This looks like Polycythemia. Polycythemia is a bone marrow disorder where the body produces too many red cells.

We call this “Relative Polycythemia.” It is an artifact. Conversely, if you are anemic but dehydrated, your Hematocrit might look “normal.”

The fluid loss masks the lack of red cells. We only discover the true anemia once you are rehydrated. This can delay necessary treatment for anemia.

White Blood Cells and Platelets

While less volatile than red cells, white blood cells (WBC) and platelets can also appear elevated. This is due to hemoconcentration. A marginally high WBC count is often interpreted as a sign of infection.

Clinicians might look for a low-grade infection or inflammation. However, in many cases, it is simply a density issue. Before prescribing antibiotics or searching for hidden infections, we must rule out dehydration.

Platelets are also prone to “clumping” in dehydrated samples. This can cause the machine to miscount them. It might trigger a false alarm for a clotting disorder.

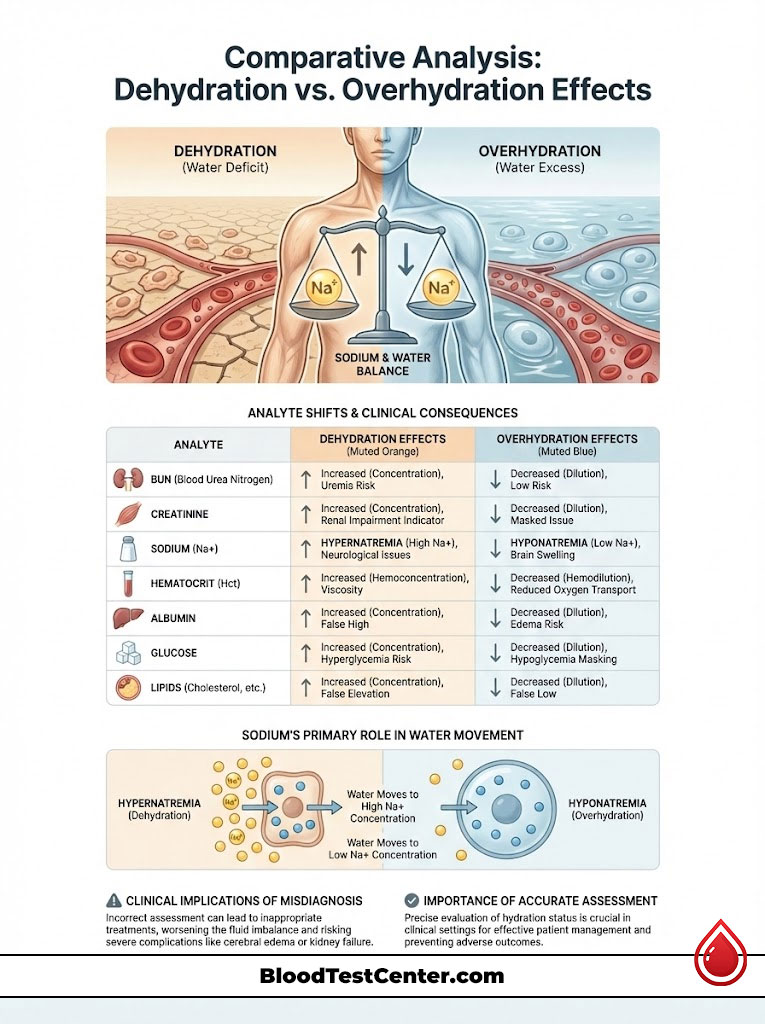

Comparative Analysis: Dehydration vs. Overhydration Effects

To visualize how these shifts occur, I have compiled a comparison. This table highlights how fluid extremes affect specific analytes. It shows the directional shift and the potential clinical error.

| Analyte (Marker) | Effect of Dehydration (Hemoconcentration) | Effect of Overhydration (Hemodilution) | Clinical Consequence of Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUN (Blood Urea Nitrogen) | ↑ Significant Increase | ↓ Decrease | False diagnosis of kidney failure or heart failure. |

| Creatinine | ↑ Slight Increase | ↔ Stable / Slight Decrease | Miscalculation of eGFR; potential medication dosing errors. |

| Sodium (Na+) | ↑ Increase (Hypernatremia) | ↓ Decrease (Hyponatremia) | Confusion regarding electrolyte balance; seizure risk assessment. |

| Hematocrit (Hct) | ↑ Increase | ↓ Decrease | Masking of anemia (if dehydrated) or false anemia diagnosis (if overhydrated). |

| Albumin | ↑ Increase | ↓ Decrease | False liver health assessment; albumin is a key hydration proxy. |

| Glucose | ↑ Slight Increase | ↔ Minimal Change | Potential misinterpretation of pre-diabetes status. |

| Lipids (Cholesterol) | ↑ Increase (5-10%) | ↓ Decrease | Unnecessary initiation of statin therapy. |

Analysis of Sodium: Sodium is the primary electrolyte that dictates water movement. “Hypernatremia” (high sodium) is almost synonymous with dehydration in an outpatient setting.

If your sodium is 148 mEq/L (normal is 135-145), and your glucose is normal, you are likely water-depleted. We rarely see true salt overload. We see water deficiency.

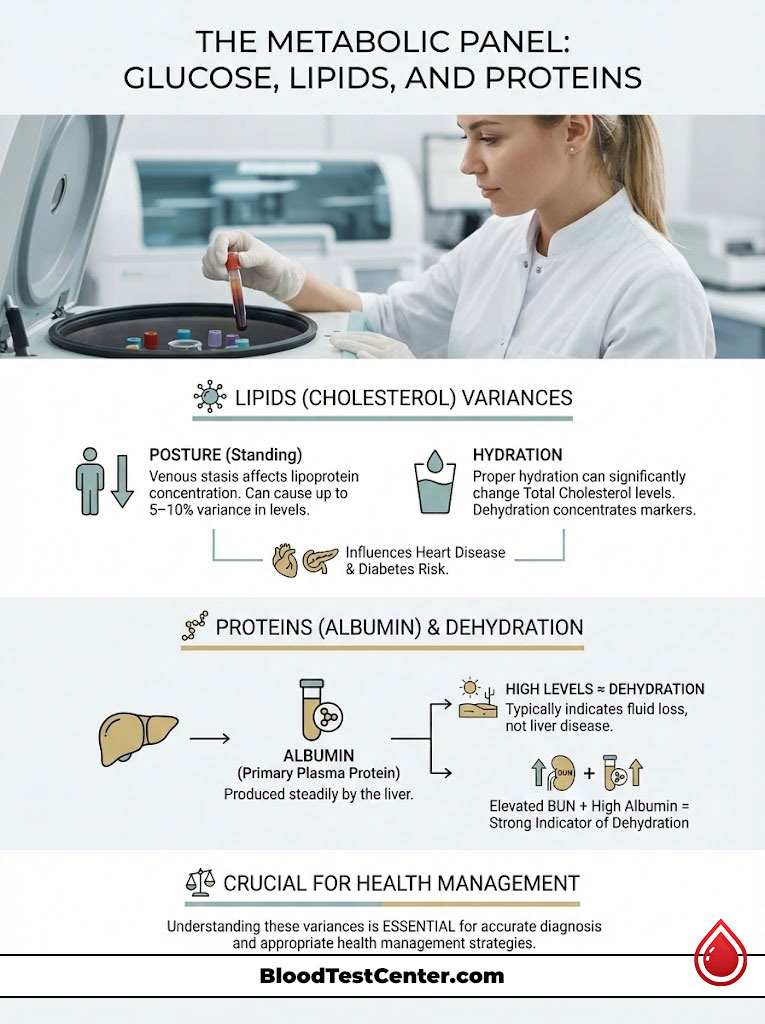

The Metabolic Panel: Glucose, Lipids, and Proteins

Moving beyond the kidneys and blood cells, we see significant variances in metabolic markers. These markers determine your risk for heart disease and diabetes.

The Lipid Profile Variance

Many patients do not realize that cholesterol is affected by posture and fluid. Studies have demonstrated a variance of 5% to 10% in Total Cholesterol. This also applies to Triglycerides.

This variance depends on hydration status and how long a patient has been standing. Standing causes venous stasis. If you are dehydrated, the lipoproteins become more concentrated.

A Total Cholesterol of 210 mg/dL could easily be 195 mg/dL with proper hydration. For a patient on the borderline of needing statin therapy, this is a critical distinction. It is the difference between lifestyle changes and a lifetime prescription.

Albumin: The Gold Standard Proxy

Albumin is the most abundant protein in your plasma. It is produced by the liver. The liver is a steady organ.

It does not suddenly decide to overproduce albumin for no reason. Therefore, “Hyperalbuminemia” (high albumin) is almost exclusively caused by dehydration. In pathology, when I see high albumin, I immediately look at the BUN.

If both are high, the diagnosis is dehydration. It is not liver disease. It is not kidney failure.

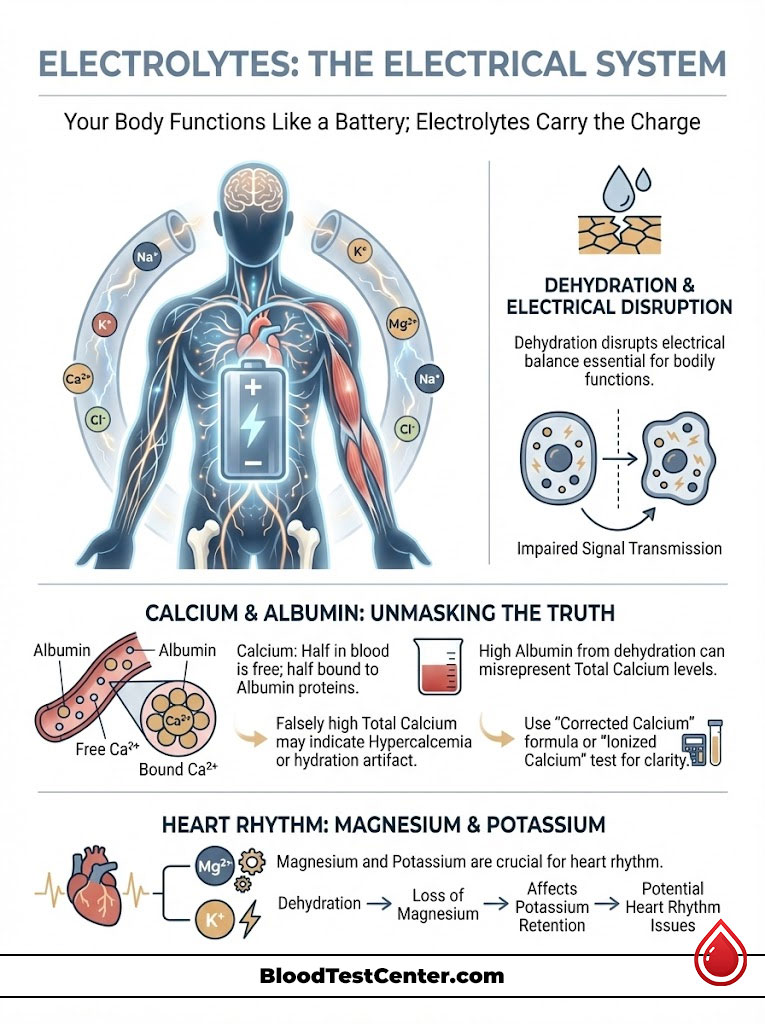

Electrolytes: The Electrical System

Your body functions like a battery. Electrolytes are the ions that carry the charge. Dehydration disrupts this delicate electrical balance.

Calcium and the Albumin Connection

Calcium levels are tricky. About half of the calcium in your blood floats freely. The other half rides piggyback on Albumin proteins.

If your Albumin is falsely high due to dehydration, your Total Calcium will also read high. This can look like Hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia can be a sign of parathyroid tumors.

However, it is often just a hydration artifact. To fix this, doctors use a “Corrected Calcium” formula. Or, we order an “Ionized Calcium” test, which ignores the protein binding.

Magnesium and Potassium

These intracellular electrolytes are vital for heart rhythm. Dehydration can cause shifts in these levels. Often, dehydration leads to a loss of Magnesium through urine.

Low Magnesium makes it hard for the body to hold onto Potassium. This double deficiency can cause heart palpitations. Patients often come to the ER fearing a heart attack, when they simply need fluids and electrolytes.

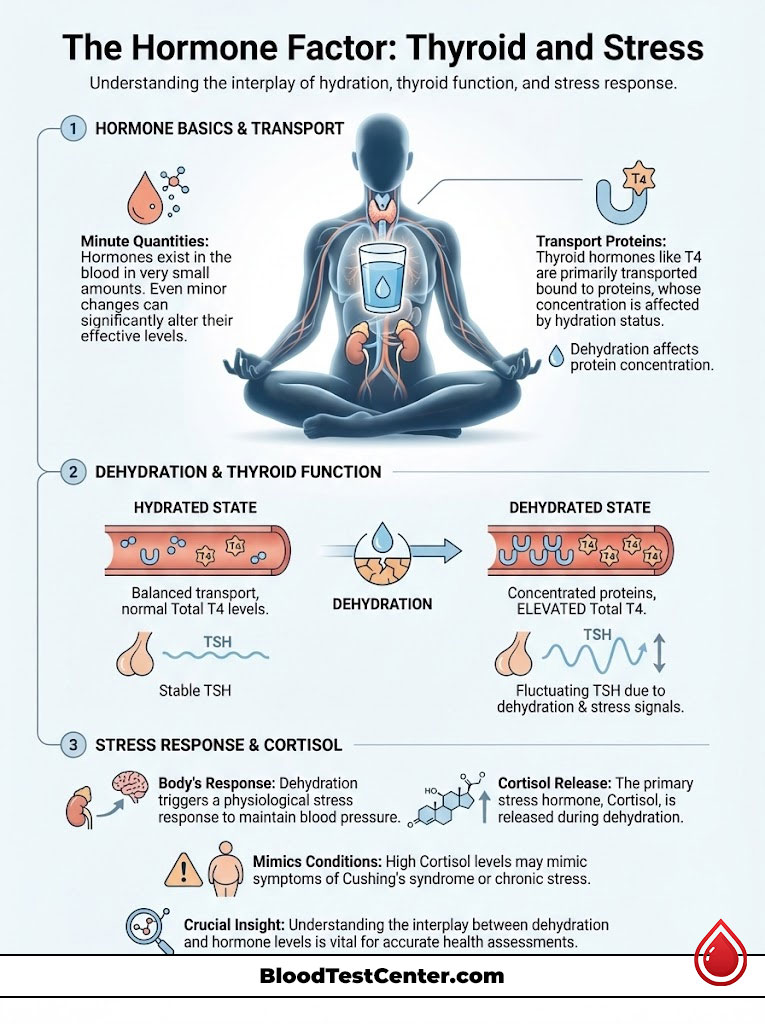

The Hormone Factor: Thyroid and Stress

Hormones circulate in the blood in minute quantities. Even small changes in blood volume can alter their measured levels. This is true for thyroid and stress hormones.

Thyroid Function Tests (TSH, T4)

Thyroid hormones like T4 are transported by proteins. As we discussed with Albumin, dehydration concentrates proteins. This can lead to a slight elevation in Total T4 levels.

Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH) is less affected but can still fluctuate. If you are dehydrated, the stress on the body can also suppress TSH slightly. This creates a confusing picture for the endocrinologist.

Cortisol and Adrenal Stress

Dehydration is a physical stressor. It triggers the release of Cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone. A high Cortisol level on a blood test might look like Cushing’s syndrome or chronic stress.

In reality, it might just be the body’s reaction to being thirsty. The body is fighting to maintain blood pressure without enough fluid. This fight releases stress hormones.

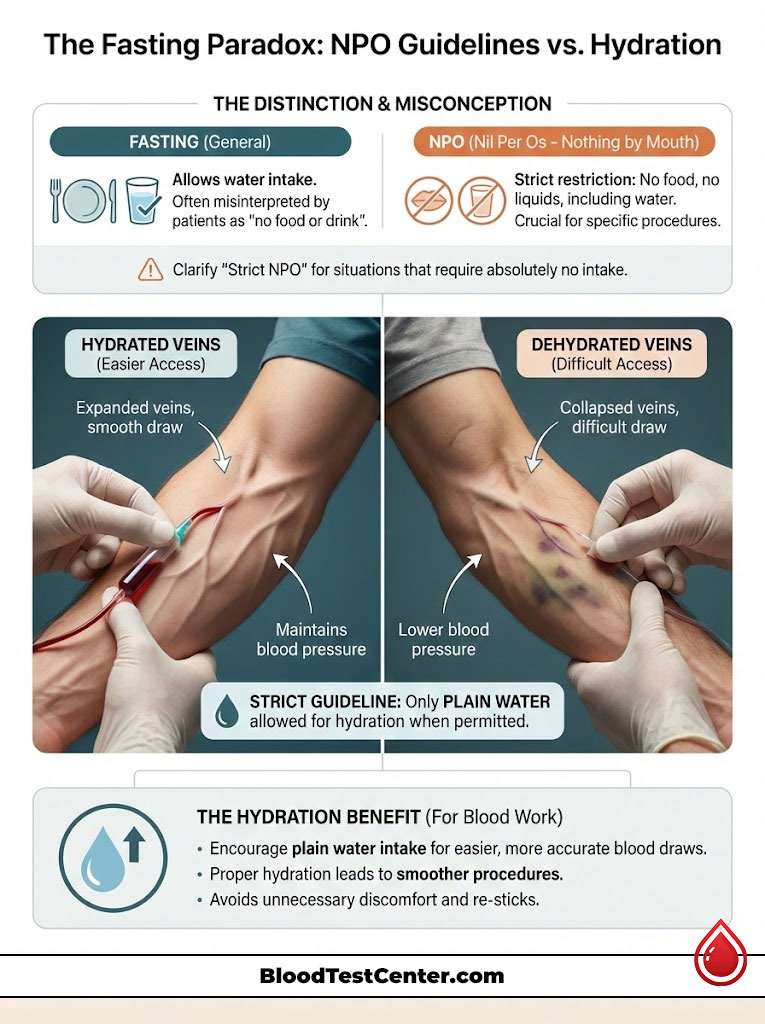

The “Fasting” Paradox: NPO Guidelines vs. Hydration

There is a massive misunderstanding regarding fasting blood work. Patients often confuse “Fasting” with “NPO.” NPO stands for “Nil Per Os,” or Nothing by Mouth.

Unless your physician or the lab specifically instructs “Strict NPO,” you can drink water. Strict NPO is usually reserved for surgical procedures or specific gastric tests. Fasting for blood work almost always allows for water consumption.

In fact, we encourage it. It makes the entire process smoother and more accurate.

Why Water is Essential for the Draw

Water maintains blood pressure. It expands the veins. A hydrated vein is bouncy and turgid.

This makes it easy for the phlebotomist to locate and access. A dehydrated vein is flat. It feels cord-like and is prone to rolling away from the needle.

However, we must be strict about what counts as hydration.

- Black Coffee? No. Caffeine is a mild diuretic, which can counteract hydration.

- Tea? No. Even herbal teas can have compounds that interfere.

- Lemon Water? No. Even the trace carbohydrates in lemon juice can disturb a fasting glucose or insulin test.

The guideline is simple: Plain water only.

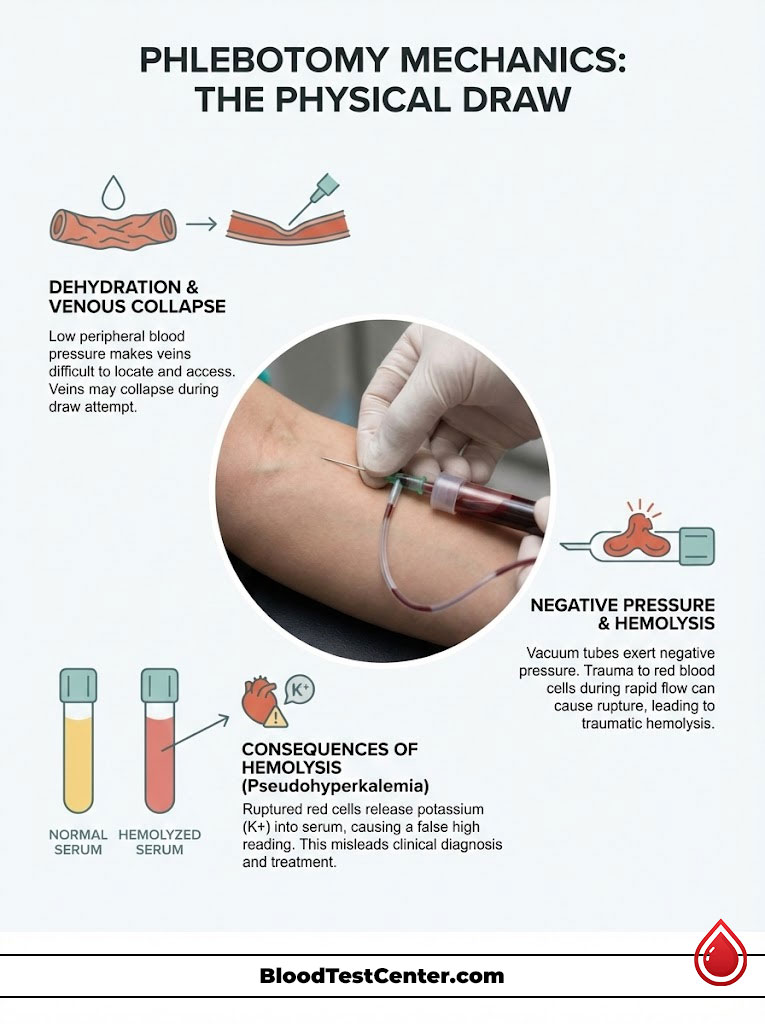

Phlebotomy Mechanics: The Physical Draw

Dehydration does not just change the chemistry. It changes the physics of the blood draw. This leads to mechanical errors that ruin the sample quality.

Venous Collapse and Traumatic Hemolysis

When a patient is dehydrated, their peripheral blood pressure is lower. The veins are not fully inflated. When the phlebotomist applies the vacuum tube to the needle, suction is created.

This negative pressure can cause the vein walls to collapse inward. This blocks the flow of blood. This forces the phlebotomist to adjust the needle or pull harder.

This physical trauma shears the red blood cells as they are sucked into the tube. This rupturing of cells is called hemolysis. It turns the serum pink instead of yellow.

The Potassium Spike (Pseudohyperkalemia)

Red blood cells are bags full of Potassium. When they rupture due to a difficult draw, that Potassium spills out. It mixes with the serum, which is the liquid part we test.

The analyzer detects this high Potassium and flags it. I cannot tell you how many patients are sent to the Emergency Room for “Critical High Potassium.” High Potassium can stop the heart.

However, upon retesting, their potassium is normal. The high reading was an artifact caused by traumatic hemolysis from a dehydrated vein. This is the definition of a pre-analytical variable causing real-world harm.

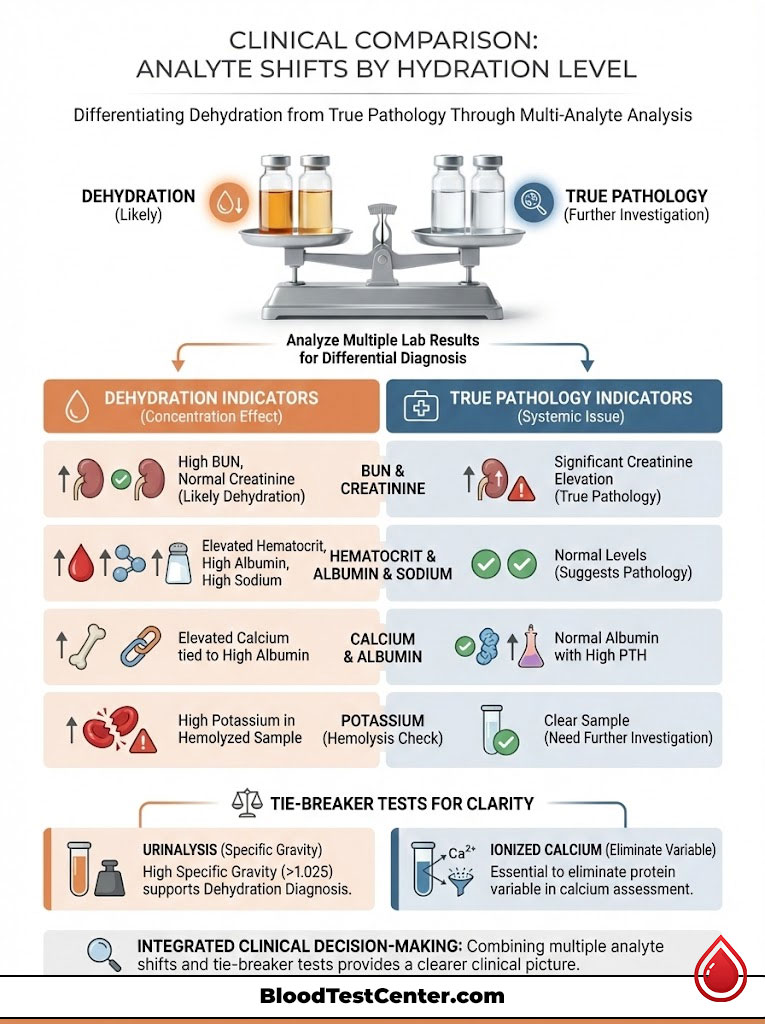

Clinical Comparison: Analyte Shifts by Hydration Level

How does a clinician tell the difference between a dehydrated patient and a sick patient? We look for patterns. A single abnormal number is rarely a diagnosis.

It is the constellation of numbers that tells the story. We look at how different markers move together.

| Observation in Lab Results | Likely Dehydration (Artifact) | Likely True Pathology (Disease) | The Tie-Breaker Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| High BUN | Creatinine is normal or slightly elevated; Ratio > 20:1. | Creatinine is also significantly high; Ratio < 15:1. | Urinalysis: High Specific Gravity (>1.025) indicates dehydration. |

| High Hematocrit | Albumin and Sodium are also elevated. | Albumin and Sodium are normal. | Erythropoietin (EPO) level check. |

| High Potassium | Sample is noted as “Hemolyzed” (pink serum). | Sample is clear (non-hemolyzed). | Re-draw sample with proper hydration. |

| High Calcium | Albumin is high (Calcium binds to Albumin). | Albumin is normal; PTH is high. | Ionized Calcium test (removes protein variable). |

Vulnerable Populations: Pediatric and Geriatric Considerations

The impact of hydration is not uniform across all ages. Certain demographics are at higher risk for blood test results skewed by fluid status. Their physiology reacts differently to fluid loss.

The Geriatric Thirst Deficit

As we age, our physiological thirst drive diminishes. A 75-year-old patient does not feel thirsty until they are already significantly dehydrated. Consequently, geriatric patients are chronically underhydrated.

When we interpret their kidney function tests, we must be very careful. We should not diagnose Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) based solely on a marginally high Creatinine. We must ensure they are hydrated first.

Furthermore, older veins are more fragile. Dehydration makes them even more brittle. This increases the risk of the “blown vein” and subsequent hemolysis we discussed earlier.

Pediatric Phlebotomy

Children have smaller veins and less blood volume. Dehydration makes pediatric phlebotomy notoriously difficult. The struggle to find a vein often leads to prolonged tourniquet application.

Leaving a tourniquet on too long causes venous stasis. The blood pools and concentrates locally. This elevates protein and cell counts even if the child’s systemic hydration is okay.

Parents should ensure children drink plenty of water before a draw. It reduces the pain of the stick and improves result accuracy.

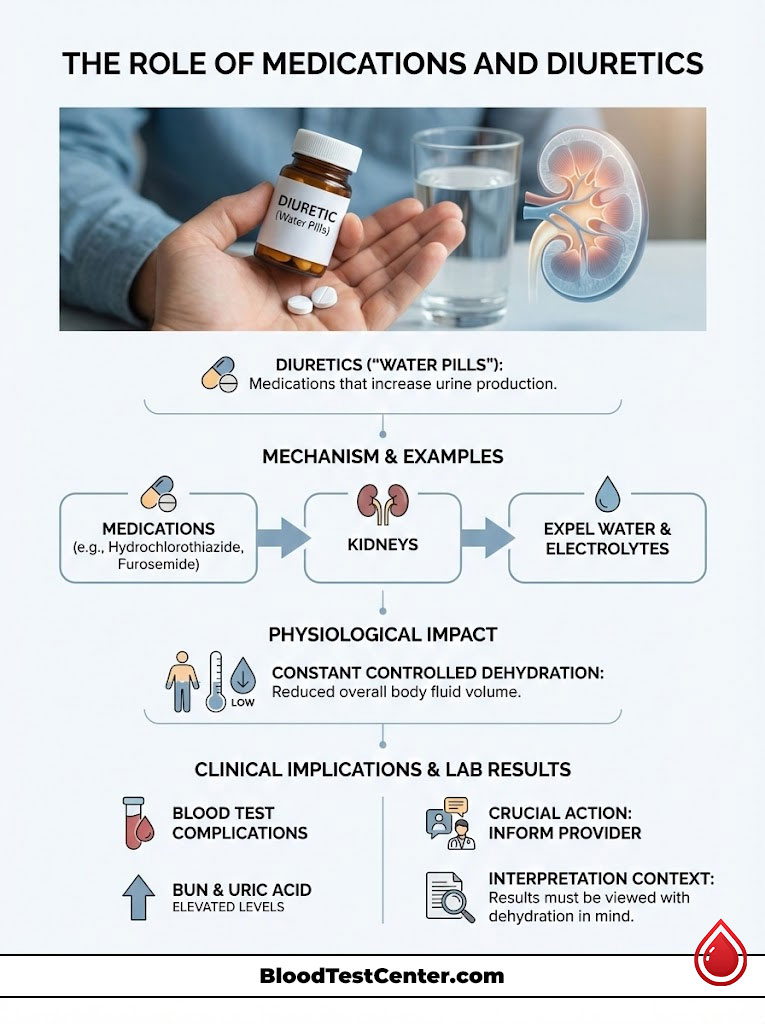

The Role of Medications and Diuretics

Many patients take medications that intentionally alter hydration status. Diuretics, or “water pills,” are common for blood pressure. Drugs like Hydrochlorothiazide or Furosemide force the kidneys to expel water.

If you take these medications, you are in a constant state of controlled dehydration. This is their mechanism of action. However, it complicates blood tests.

Patients on diuretics often show chronically elevated BUN and Uric Acid. It is vital to tell your phlebotomist and doctor about these meds. They need to interpret your results with that “controlled dehydration” in mind.

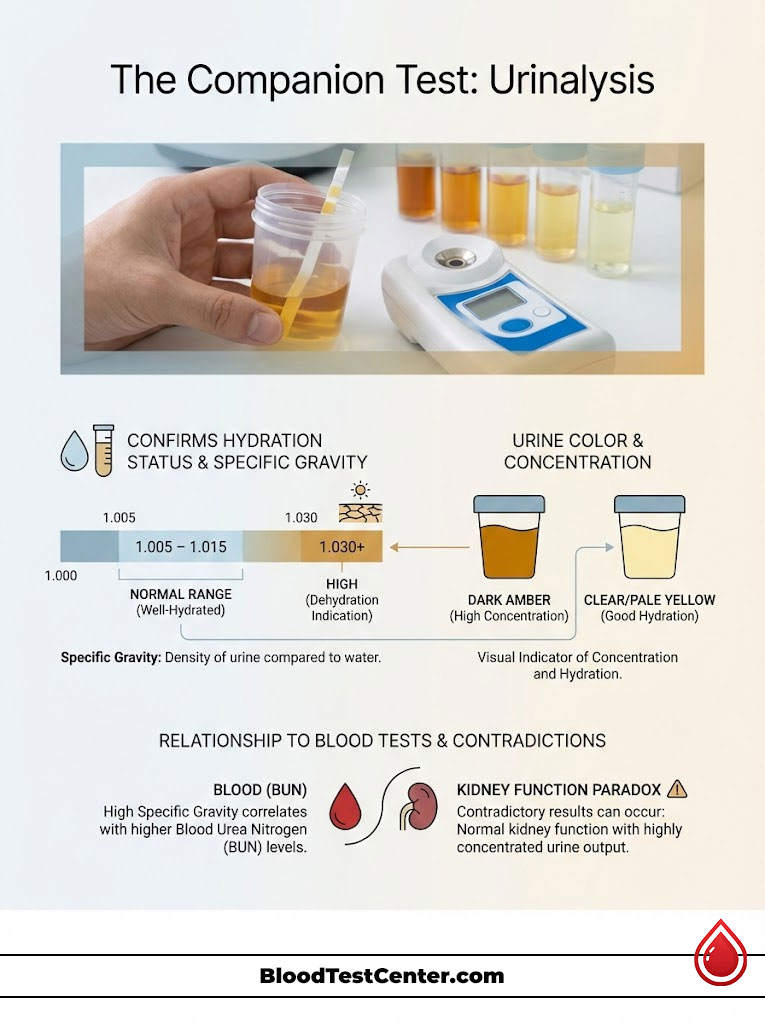

The Companion Test: Urinalysis

Blood tests do not exist in a vacuum. The best way to confirm if a blood test is skewed by dehydration is to look at the urine. The Urinalysis provides the “ground truth” of hydration.

Specific Gravity

This measures the density of urine compared to pure water. Water has a specific gravity of 1.000. Well-hydrated urine should be between 1.005 and 1.015.

If your urine Specific Gravity is 1.030, your kidneys are screaming for water. They are concentrating the urine to the maximum to save fluid. If we see this alongside high BUN in the blood, we know the blood results are an artifact.

Urine Color and Clarity

While less scientific, visual inspection matters. Dark amber urine correlates with high concentration. Clear, pale yellow urine indicates good hydration.

If a patient has “Kidney Failure” numbers in their blood but is producing copious amounts of clear urine, the diagnosis is contradictory. We must investigate further.

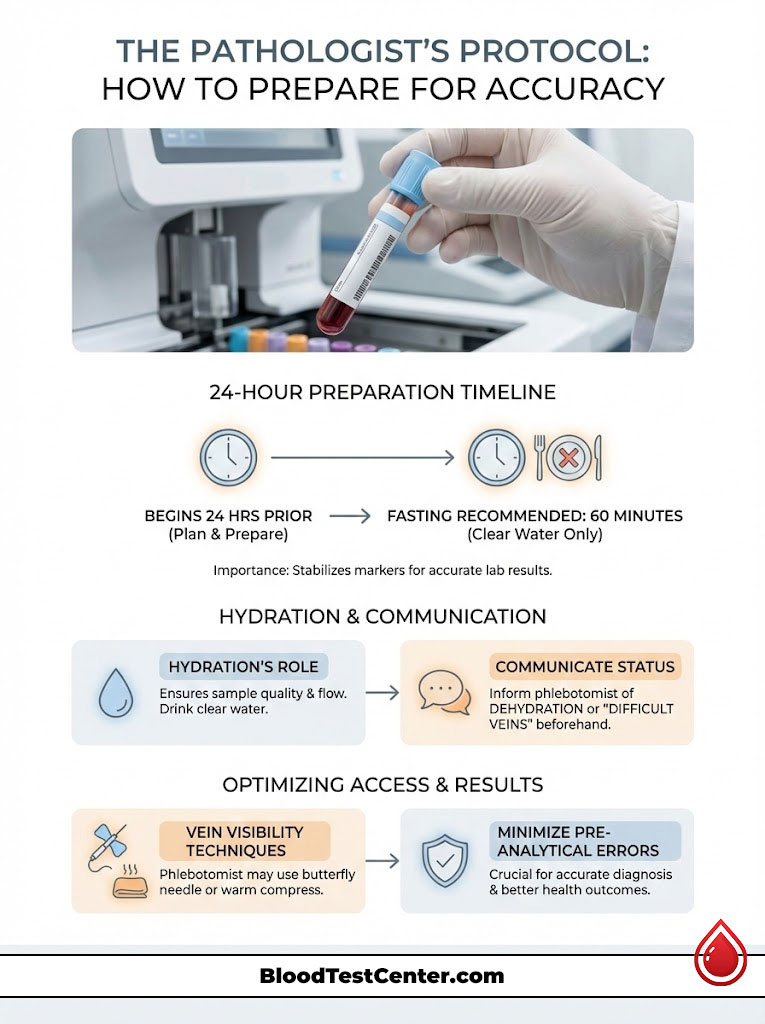

The Pathologist’s Protocol: How to Prepare for Accuracy

To ensure your lab results reflect your health and not your water intake, I recommend a specific protocol. This is what I tell my own family members. It minimizes pre-analytical error.

The 24-Hour Timeline

- The Day Before: Avoid alcohol. Alcohol is a diuretic and suppresses antidiuretic hormone. This causes you to lose fluid faster than you take it in. Eat water-rich foods like fruits and vegetables.

- The Night Before: Drink a standard 8oz glass of water before bed. This combats the fluid loss that naturally occurs during sleep through breathing and sweating.

- The Morning Of (The Pre-Draw Bolus): This is the most critical step. Unless you are on strict fluid restrictions for heart failure or dialysis, drink 16oz (two cups) of plain water 60 minutes before your appointment.

Why 60 minutes? This gives the fluid time to absorb from the stomach into the vascular system. It plumps up the veins and normalizes plasma volume.

Communication is Key: If you know you are dehydrated, tell the phlebotomist immediately. If you have “difficult veins,” let them know. They can use a smaller butterfly needle or apply a warm compress to dilate the veins.

Summary & Key Takeaways

The human body is dynamic. A blood test is a snapshot of a moving target. Hydration status is the lens through which we view that snapshot.

If the lens is distorted by dehydration, the picture will be wrong. We must account for this variable to ensure accurate medical care.

- Hemoconcentration is the biological mechanism where fluid loss concentrates blood components. This leads to false highs in lab results.

- Red Flags: A combination of High BUN, High Albumin, and High Hematocrit usually points to dehydration. It rarely indicates simultaneous organ failure.

- Preparation: Drinking water before a “fasting” blood draw is generally permitted. It is highly recommended to prevent false positive lab results.

- Vein Health: Hydration makes veins easier to access. This prevents traumatic draws that can rupture cells and ruin the sample.

An accurate diagnosis begins with a hydrated patient. By controlling this variable, you ensure that your medical team is treating you. They should not be treating an artifact of your thirst.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can dehydration cause false positive lab results?

Yes, dehydration triggers a process called hemoconcentration, where the lack of plasma water artificially inflates the concentration of blood solids. This frequently leads to false spikes in markers like BUN, albumin, and hematocrit, which can mimic serious conditions like kidney failure or blood disorders when no disease is actually present.

Can I drink water before a fasting blood test?

In almost all cases, drinking plain water is highly encouraged before a fasting blood draw to prevent skewed results. Unless your physician has specifically ordered you to be “Strict NPO” for a surgical procedure, water will not interfere with your fasting glucose or lipid levels and will actually improve the accuracy of the test.

How does hydration affect my BUN and creatinine levels?

Dehydration causes the body to reabsorb urea back into the bloodstream to conserve water, causing Blood Urea Nitrogen (BUN) to skyrocket while creatinine remains relatively stable. This creates a BUN/Creatinine ratio greater than 20:1, a classic diagnostic sign of “pre-renal azotemia,” which indicates low blood flow due to thirst rather than intrinsic kidney damage.

Can being dehydrated lower my eGFR score?

Because the Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) is calculated using your creatinine levels, any dehydration-induced rise in creatinine will mathematically result in a lower eGFR. I have seen many patients mistakenly diagnosed with Stage 3 Kidney Disease whose eGFR scores returned to the normal range of >90 after simply rehydrating and retesting.

Does dehydration affect my cholesterol or lipid panel results?

Dehydration can cause a 5% to 10% variance in total cholesterol and triglycerides due to the concentration of lipoproteins in a lower volume of plasma. For patients on the borderline of needing statin therapy, this pre-analytical variable can be the difference between a clean bill of health and an unnecessary lifetime prescription.

Why is my hematocrit high when I am dehydrated?

Hematocrit measures the volume percentage of red blood cells in your blood; when you lose plasma water, those cells become more densely packed. This results in “relative polycythemia,” an artifact that makes it appear as though you have an overproduction of red cells when, in reality, you are simply fluid-depleted.

Can dehydration cause a false high potassium reading?

Dehydration often leads to “traumatic hemolysis” during the draw because flat, dehydrated veins are more likely to collapse or require needle adjustment. This physical trauma ruptures red blood cells, spilling their internal potassium into the sample and creating a “pseudohyperkalemia” reading that can trigger unnecessary emergency room visits.

What does a high albumin level mean in a blood test?

In clinical pathology, hyperalbuminemia (high albumin) is considered a gold-standard proxy for dehydration. Since the liver produces albumin at a very steady rate, a high concentration is almost exclusively caused by a decrease in the water volume of the blood rather than a liver pathology.

How does hydration status affect the ease of a blood draw?

Proper hydration ensures your veins are turgid and “bouncy,” making them easy for the phlebotomist to access. Dehydrated veins are often flat and cord-like, which increases the likelihood of the vein “rolling” or collapsing under the vacuum pressure of the collection tube, leading to bruising and sample degradation.

What is the difference between hemoconcentration and hemodilution?

Hemoconcentration is the crowding of blood components due to fluid loss (dehydration), leading to false highs. Hemodilution is the thinning of blood components due to fluid excess (overhydration or IV fluids), which can cause “false anemia” by making red blood cell counts appear lower than they truly are.

How do pathologists use urinalysis to confirm blood test accuracy?

We look specifically at the Urine Specific Gravity; a reading above 1.025 indicates that the kidneys are aggressively concentrating urine to save water. If we see this high specific gravity alongside elevated blood markers like BUN, we can confirm that the patient is dehydrated and that the blood results are likely artifacts.

What is the best way to hydrate before a blood draw?

The ideal protocol is to drink 16 ounces (two cups) of plain water roughly 60 minutes before your appointment. This allows enough time for the water to be absorbed into your vascular system to expand your plasma volume and stabilize your analytes without causing excessive dilution.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. The insights provided by the clinical pathologist are intended to educate patients on laboratory variables. Always consult with your primary care physician or a qualified healthcare professional regarding your specific lab results and before making any changes to your medication or hydration routines.

References

- Association for Diagnostics & Laboratory Medicine (formerly AACC) – https://www.myadlm.org – Source for statistics regarding pre-analytical laboratory errors and testing standards.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH) – https://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus – Clinical data regarding BUN/Creatinine ratios and kidney function markers.

- Journal of Clinical Pathology – BMJ Journals – Research regarding the effects of posture and hydration on lipid and protein concentration.

- Mayo Clinic Laboratories – https://www.mayocliniclabs.com – Reference values for Hematocrit, Albumin, and the physiological effects of hemoconcentration.

- American Journal of Kidney Diseases – National Kidney Foundation – Studies on eGFR variance and pre-renal azotemia caused by fluid volume depletion.

- World Health Organization (WHO) – Laboratory guidelines for phlebotomy and specimen collection quality control.