You receive an email notification that your lab results are ready. You log into the patient portal, scroll past the metabolic panel, and stop at the Complete Blood Count (CBC) section. There it is. A red flag, an exclamation point, or simply the word “Low” sitting next to Hemoglobin.

Table of Contents

Your heart skips a beat. The immediate assumption is often the worst-case scenario. However, a single number on a lab report rarely tells the whole story. To truly understand what is happening inside your body, you need to interpret that number within the context of the entire blood panel.

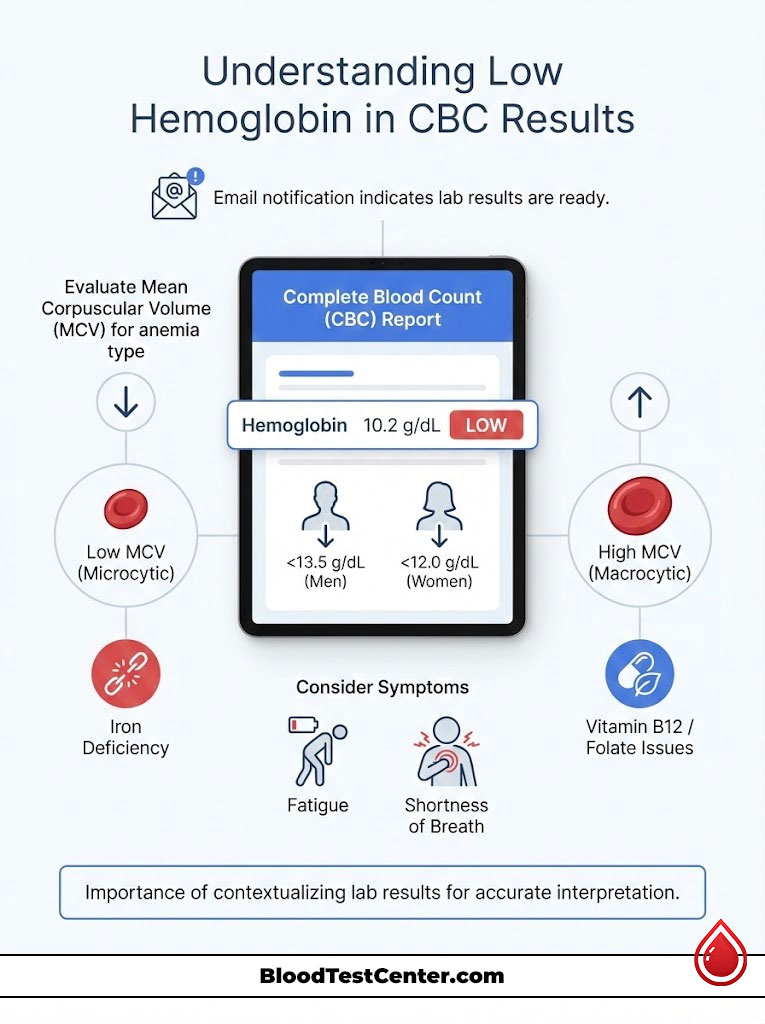

To interpret low hemoglobin in your CBC, compare your result against the standard reference range (typically <13.5 g/dL for men and <12.0 g/dL for women). Next, evaluate the Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV) to identify the type of anemia. Low MCV suggests iron deficiency, while high MCV often indicates Vitamin B12 or folate issues. Always review these indices alongside symptoms like fatigue or shortness of breath to determine clinical significance.

This guide serves as a comprehensive resource to help you decode your CBC test results. We will move beyond the basic definitions and explore the physiological mechanics of oxygen transport, the nuance of reference ranges, and the specific “red flags” that doctors look for when analyzing your blood work.

Understanding the Physiology of Hemoglobin and Oxygen Transport

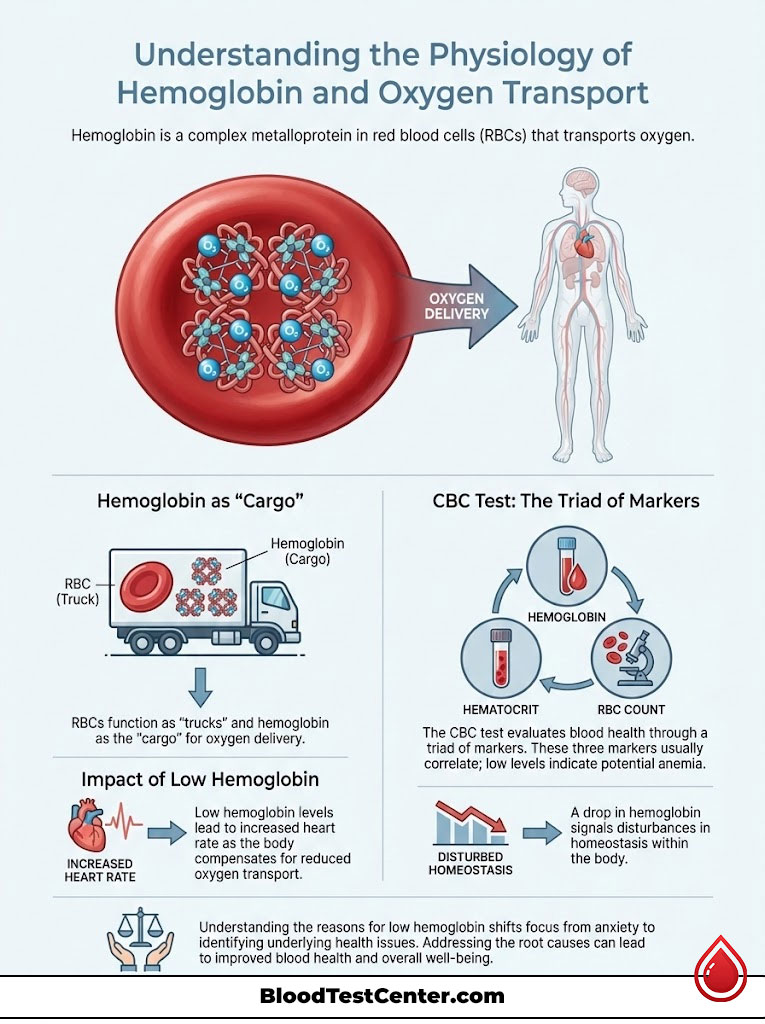

Hemoglobin is not just a metric on a spreadsheet. It is the engine of your respiratory system. It is a complex metalloprotein contained within your red blood cells (RBCs) that bonds with oxygen in the lungs and delivers it to tissues throughout your body.

Think of your bloodstream as a busy highway system. The red blood cells are the trucks, and hemoglobin is the cargo container on those trucks. If you have low hemoglobin, it means you have fewer containers available to transport oxygen. Consequently, your heart has to work harder to pump blood faster to ensure your brain and muscles get the oxygen they require. This compensatory mechanism is why a rapid heart rate is often one of the first physical signs of anemia.

The CBC Test Context: The Triad of Blood Health

When interpreting low hemoglobin, you cannot look at it in isolation. Hematologists and primary care providers analyze a “triad” of values found in your CBC test results. These three markers function as a checks-and-balances system for your blood health.

- RBC Count (Red Blood Cell Count): This measures the total number of red blood cells circulating in your body. A low count suggests the factory (bone marrow) is sluggish or the cells are being destroyed.

- Hemoglobin (Hgb): This measures the total amount of oxygen-carrying protein by weight. This is the most direct measure of your blood’s functional capacity.

- Hematocrit (Hct): This measures the percentage of your total blood volume that is made up of red blood cells. Think of this as the “thickness” or density of the red cells in your blood plasma.

These three numbers usually move in tandem. If your hemoglobin levels are low, your hematocrit is likely low as well. When all three are suppressed, the condition is clinically defined as anemia.

Why the Body Drops Production of Hemoglobin

The body is generally efficient at maintaining balance, or homeostasis. A drop in hemoglobin levels usually signals a disruption in one of three critical biological areas.

- Production Failure: The bone marrow is not making enough cells. This is often due to a lack of raw materials like iron, Vitamin B12, or folate. It can also be caused by a lack of the hormonal signal Erythropoietin (EPO), which is produced by the kidneys.

- Destruction (Hemolysis): The body is destroying cells faster than they can be replaced. This can happen in autoimmune conditions or genetic disorders like Sickle Cell Disease.

- Loss (Hemorrhage): You are losing blood somewhere. This can be visible, such as heavy menstruation, or hidden, such as a slow leak in the gastrointestinal tract.

Understanding this mechanism is the first step in moving from anxiety to action. It shifts the focus from “my number is low” to “why is my system struggling to keep up?”

Establishing the Baseline: Standard Hemoglobin Reference Ranges

Before you can accurately interpret low hemoglobin, you must define “normal.” It is important to note that reference ranges can vary slightly depending on the laboratory and the specific equipment used to analyze the blood sample. However, most US institutions, including the Mayo Clinic and the American Society of Hematology, follow similar baselines.

The Variability of Normal Hemoglobin Levels

Context matters significantly when reading a lab report. A level that is considered low hemoglobin for a man might be perfectly normal for a menstruating woman.

Similarly, geography plays a role. Someone living at a high altitude (like Denver, Colorado) will naturally have higher hemoglobin levels because the air is thinner. The body compensates for the lower oxygen availability in the atmosphere by producing more red blood cells to capture every available molecule of oxygen. Therefore, a “normal” reading for someone at sea level might actually indicate anemia for someone living in the mountains.

Standard Hemoglobin Levels by Demographic

The following data reflects general medical standards in the USA. If your numbers fall slightly outside these ranges, it does not always indicate a medical crisis. However, significant deviations require clinical investigation.

Table 1: Standard Hemoglobin Reference Ranges & Critical Limits

| Demographic Group | Normal Range (g/dL) | Mild Anemia Threshold | Critical / Transfusion Level |

| Adult Men | 13.5 – 17.5 | < 13.0 | < 7.0 |

| Adult Women | 12.0 – 15.5 | < 12.0 | < 7.0 |

| Pregnant Women | 11.0 – 13.0 | < 11.0 (Trimester dependent) | < 7.0 |

| Newborns | 14.0 – 24.0 | Varies by weeks | < 10.0 |

| Children (1-6 yrs) | 9.5 – 14.0 | < 9.5 | < 7.0 |

Defining Dangerously Low Hemoglobin Levels

Patients often ask, “At what point is this an emergency?”

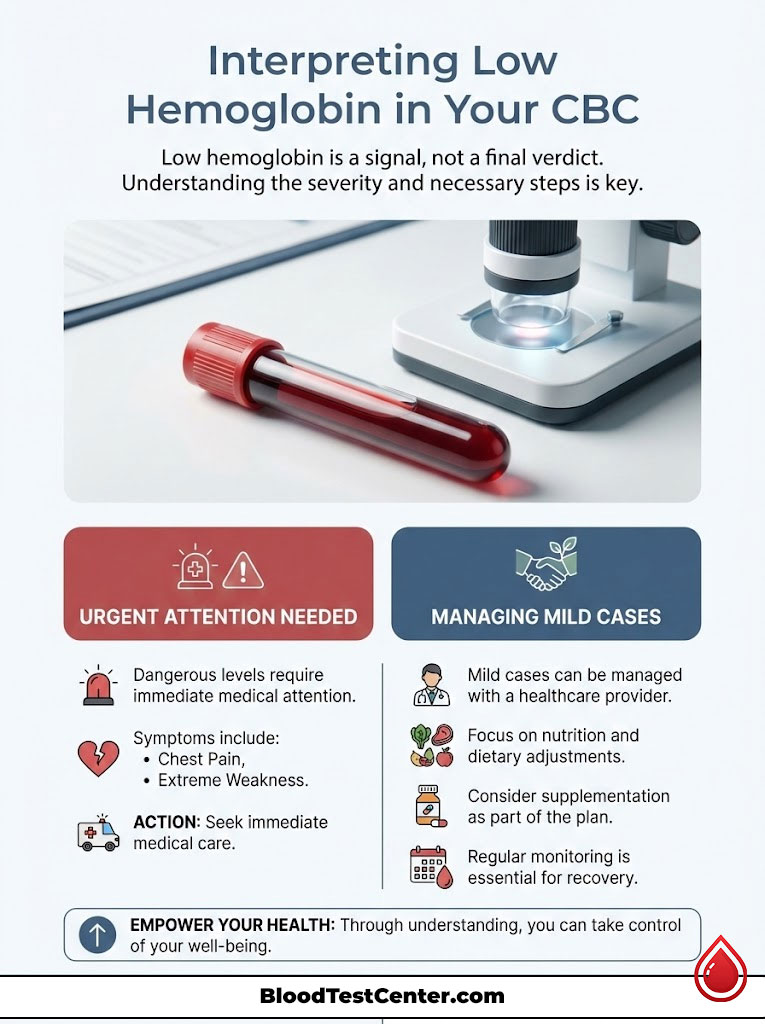

While symptoms can appear at varying levels depending on how quickly the drop occurred, levels below 7.0 g/dL are universally considered dangerously low hemoglobin.

At this level, the risk of heart failure increases dramatically because the heart cannot pump fast enough to oxygenate the vital organs. This is the standard threshold where hospitals will consider a blood transfusion to prevent tissue damage, especially if the patient is symptomatic or has a history of heart disease.

The Investigative Triad: Using CBC Indices to Interpret Anemia

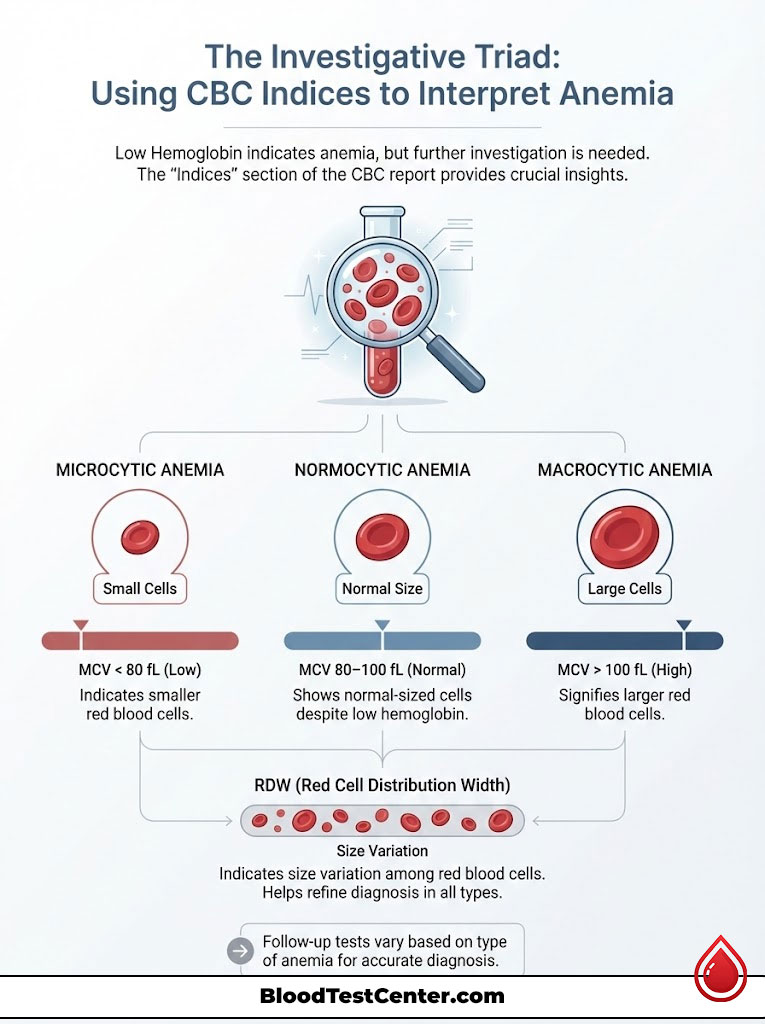

This is the most critical section for interpreting your CBC test results. A low hemoglobin number tells you that you have anemia, but it does not tell you what kind of anemia you have. To find the cause, you must look at the “Indices” section of your report.

These indices describe the physical characteristics of your red blood cells. The most valuable metric here is the MCV (Mean Corpuscular Volume). This number measures the average size of your red blood cells. The size of the cell gives the doctor a direct clue as to what nutrient is missing or what process is broken in the bone marrow.

Microcytic Anemia: Interpreting Low MCV (< 80 fL)

If your hemoglobin levels are low and your MCV is also low (usually below 80 fL), your red blood cells are smaller than normal. This is classified as Microcytic Anemia.

- Primary Cause: Iron deficiency anemia. This is the most common cause of anemia in the USA. Iron is the core building block of hemoglobin. When the body lacks iron, it cannot build full-sized hemoglobin proteins. Consequently, the bone marrow releases small, pale, and inefficient cells.

- Secondary Causes: Thalassemia (a genetic condition affecting hemoglobin structure) or lead poisoning.

- Key Insight: If you see “Low Hgb” and “Low MCV,” the first line of inquiry is almost always evaluating your iron stores through a ferritin test.

Normocytic Anemia: Interpreting Normal MCV (80–100 fL)

This can be confusing for patients. Your hemoglobin levels are low, but the cells look perfectly normal in size. This is classified as Normocytic Anemia.

- Interpretation: The manufacturing plant (bone marrow) is building quality cells, but it simply isn’t making enough of them, or they are being lost somewhere after leaving the factory.

- Primary Causes:

- Chronic Kidney Disease: The kidneys produce a hormone called Erythropoietin that signals the bone marrow to make blood. If kidney function declines, this signal is lost, and production slows down.

- Anemia of Chronic Disease: Conditions like Rheumatoid Arthritis, Lupus, or severe infections.

- Acute Blood Loss: A sudden injury or rapid gastrointestinal bleed where the body hasn’t had time to make smaller cells yet.

Macrocytic Anemia: Interpreting High MCV (> 100 fL)

If your hemoglobin levels are low but your MCV is high (above 100 fL), your red blood cells are abnormally large. This is classified as Macrocytic Anemia.

- Primary Cause: Deficiency in Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) or Folate (Vitamin B9). These vitamins are required for the DNA synthesis needed for the cell to divide. Without them, the cell grows large but never splits, resulting in fewer, giant cells that die early.

- Secondary Causes: Liver disease, high alcohol consumption, hypothyroidism, or certain medications (like chemotherapy drugs or hydroxyurea).

Table 2: Diagnostic Guide to Interpreting Low Hemoglobin via MCV Indices

| MCV Reading | Type of Anemia | Primary Suspects | Recommended Follow-Up Tests |

| Low (< 80 fL) | Microcytic | Iron Deficiency, Thalassemia, Lead Poisoning | Ferritin, Iron Saturation, Hemoglobin Electrophoresis |

| Normal (80–100 fL) | Normocytic | Chronic Kidney Disease, Acute Blood Loss, Bone Marrow Failure | Reticulocyte Count, BUN/Creatinine, CRP |

| High (> 100 fL) | Macrocytic | B12 Deficiency, Folate Deficiency, Hypothyroidism | Vitamin B12, Folate Levels, TSH |

The Role of RDW in Interpretation

Another helpful number on your CBC test results is the RDW (Red Cell Distribution Width). This measures the variation in size between your red blood cells.

- High RDW: This means you have a mix of small and large cells. This is very common in early iron deficiency or B12 deficiency, as the body struggles to maintain consistency.

- Normal RDW: If you have low hemoglobin and low MCV but a normal RDW, it points more strongly toward a genetic condition like Thalassemia trait, where the cells are uniformly small.

Deep Dive into the Causes of Low Hemoglobin

Understanding the “why” is vital for effective treatment. Low hemoglobin is rarely a disease in itself. It is almost always a symptom of an underlying issue. We can categorize these issues into three main buckets: Nutritional, Medical, and Mechanical.

Nutritional Deficiencies and Malabsorption Issues

In the United States, diet plays a role, but malabsorption is increasingly common. You might be eating the right foods, but your body isn’t keeping the nutrients.

- Iron Deficiency: This is the leading cause globally. However, it isn’t always about diet. If you have Celiac disease, Crohn’s disease, or have had gastric bypass surgery, your gut may not be absorbing the iron you consume.

- Vitamin B12 Deficiency: Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune condition where the stomach lacks “Intrinsic Factor,” a protein needed to absorb B12. This often leads to low hemoglobin coupled with neurological symptoms like tingling in the hands or balance issues.

Internal Medicine and Chronic Disease Mechanisms

Chronic inflammation confuses the body’s iron management system.

- Anemia of Inflammation: When you are sick (e.g., with cancer, HIV, or an autoimmune flare), your immune system releases inflammatory cytokines. These chemicals tell the liver to produce Hepcidin, a molecule that blocks iron absorption and locks existing iron away in storage cells. The result is low hemoglobin despite having plenty of iron in the body. It is the body’s way of starving bacteria of iron, but it hurts the host in the long run.

- Kidney Health: As mentioned, the kidneys are the thermostat for red blood cells. As kidney function declines (measured by GFR), hemoglobin levels almost always drop due to a lack of Erythropoietin.

Blood Loss: The Silent Culprit

If production is normal, the blood must be going somewhere.

- Visible Loss: Heavy menstrual cycles (Menorrhagia) are the leading cause of iron deficiency anemia in women under 50. Often, what a patient considers “normal” flow is actually excessive and depleting iron stores month after month.

- Occult (Hidden) Loss: In men and post-menopausal women, low hemoglobin is often the first sign of slow gastrointestinal bleeding. This could come from a peptic ulcer, gastritis, polyps, or colon cancer. This is why doctors take anemia in older adults very seriously and often prescribe a colonoscopy.

Recognizing the Symptoms of Low Hemoglobin

Sometimes the symptoms appear before the lab test confirms the diagnosis. The severity of your symptoms often depends on how quickly your hemoglobin levels dropped. A slow drop allows the body to adapt, meaning you might walk around with a level of 8.0 g/dL and only feel tired. A sudden drop to 8.0 g/dL from a trauma would likely cause you to faint.

General Physical Symptoms of Anemia

- Fatigue: A deep, systemic exhaustion that sleep does not fix. It feels like your batteries are constantly at 10%.

- Pallor: Pale skin is a classic sign. However, in people with darker skin tones, check the gums, nail beds, or the inner lining of the lower eyelid (conjunctiva) for paleness.

- Dyspnea: Shortness of breath, especially when walking up stairs or exerting yourself. This happens because your lungs are working fine, but the blood cannot carry the oxygen away fast enough.

- Brain Fog: Difficulty concentrating or finding words due to lower oxygen delivery to the brain tissues.

Specific “Red Flag” Instances and Cravings

Certain symptoms point to specific causes of low hemoglobin.

- Pica: This is a distinct and unusual craving for non-food items. If you find yourself chewing massive amounts of ice, or craving clay, dirt, or cornstarch, this is a classic neurological response to severe iron deficiency.

- Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS): An uncontrollable urge to move your legs, usually at night, is frequently linked to low ferritin and low hemoglobin. Correcting the iron levels often cures the RLS.

- Koilonychia: Spoon-shaped nails that dip inward are a physical sign of long-term iron deprivation.

- Glossitis: A swollen, smooth, or sore tongue can indicate B12 or iron deficiency.

Cardiac Warning Signs

Your heart must compensate for the thin blood by pumping faster.

- Tachycardia: A resting heart rate typically above 100 bpm.

- Palpitations: Feeling your heart skipping beats, fluttering, or pounding in your chest.

- Chest Pain: In severe cases, the heart muscle itself is starving for oxygen (angina). This requires immediate emergency attention.

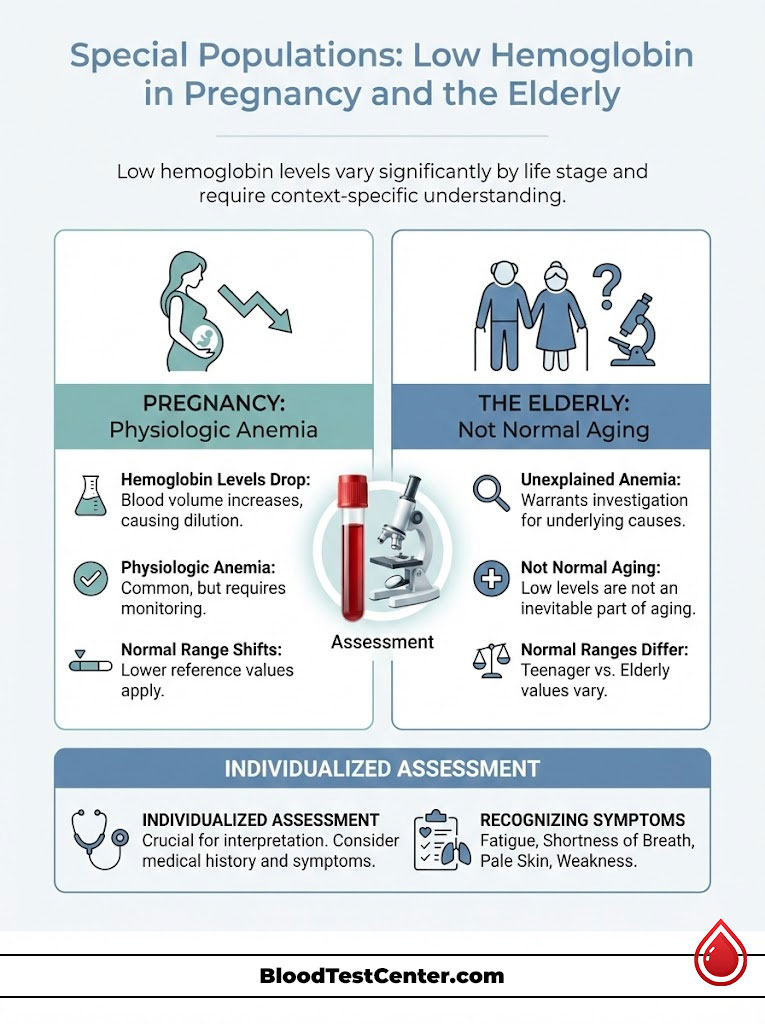

Special Populations: Low Hemoglobin in Pregnancy and the Elderly

Interpreting low hemoglobin requires adjusting for the patient’s life stage. What is normal for a teenager is not normal for a grandfather.

Interpreting Low Hemoglobin in Pregnancy

It is standard for hemoglobin levels to drop during pregnancy. This is known as “Physiologic Anemia of Pregnancy.”

- The Mechanism: A pregnant body increases its plasma volume (fluid) by about 50% to support the fetus. However, red blood cell mass only increases by about 25%. This dilutes the blood, lowering the concentration of hemoglobin.

- The Instance: A level of 11.0 g/dL is often considered acceptable in the first and third trimesters, while 10.5 g/dL may be accepted in the second trimester. However, falling below 10.0 g/dL increases the risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and postpartum hemorrhage. Strict monitoring and iron supplementation are usually required.

Unexplained Anemia in the Elderly

In patients over 65, low hemoglobin should never be dismissed as “just old age.”

- The Risk: According to geriatric studies, anemia in the elderly is associated with higher mortality, increased cognitive decline, and a greater risk of falls due to dizziness.

- The Investigation: In this demographic, low hemoglobin is a primary trigger to screen for colon cancer or Myelodysplastic Syndromes (MDS), a type of bone marrow failure. Doctors will often order a smear test to look at the cells under a microscope.

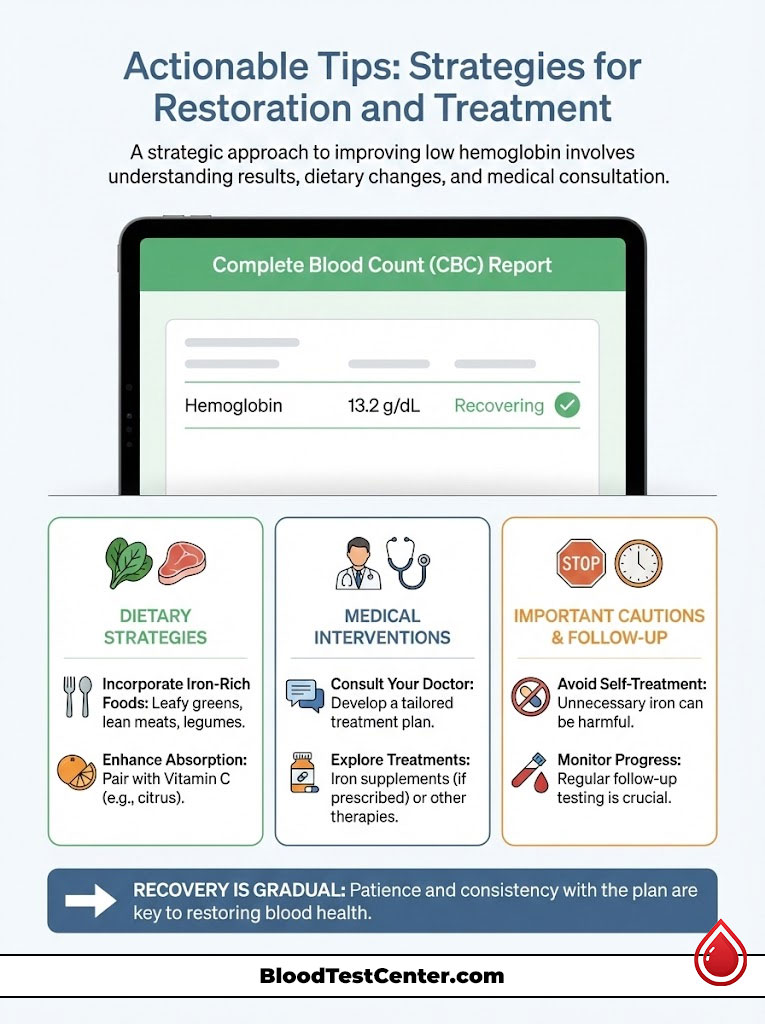

Actionable Tips: Strategies for Restoration and Treatment

Once you have interpreted your CBC test results and identified low hemoglobin, the next step is a strategic treatment plan developed with your doctor. Do not attempt to self-treat without a diagnosis, as taking iron when you don’t need it can be dangerous.

Dietary Strategies for Hemoglobin Restoration

If your indices point to nutritional deficiency, food is your first medicine.

- Heme Iron vs Non-Heme Iron: Heme iron is found in animal products like red meat, liver, and organ meats. It is absorbed 2-3 times better than non-heme iron, which is found in plant sources like spinach, lentils, and fortified cereals.

- The “Orange Juice Rule”: Vitamin C creates an acidic environment in the stomach that converts plant-based iron into a form that is easier to absorb. Drinking a glass of orange juice or taking a Vitamin C supplement with your iron-rich meal can significantly boost uptake.

- Avoid Inhibitors: Calcium and tannins block iron absorption. Do not take your iron supplement with milk, yogurt, coffee, or tea. Wait at least two hours before or after consuming these items.

Medical Interventions for Anemia

When diet is not enough, medical science steps in.

- Oral Supplements: Ferrous Sulfate or Ferrous Gluconate are standard prescriptions. However, they can cause constipation and stomach upset. Taking them every other day has been shown in recent studies to improve absorption and reduce side effects compared to daily dosing.

- Iron Infusions: For patients who cannot tolerate oral iron or have malabsorption issues (like Celiac disease or Gastric Bypass), intravenous (IV) iron delivers the mineral directly into the bloodstream, bypassing the gut entirely. This is often much faster and more effective for severe cases.

- ESAs (Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents): For patients with chronic kidney disease or those undergoing chemotherapy, these drugs mimic the hormone erythropoietin to stimulate the bone marrow to produce more red cells.

The Importance of Follow-Up Testing

Recovering from low hemoglobin is a marathon, not a sprint.

- Timeline: It typically takes 2 to 4 weeks to see an increase in hemoglobin levels after starting treatment.

- Full Recovery: It can take 3 to 6 months to fully replenish your iron stores (ferritin). Stopping treatment too early often leads to a relapse.

- Retesting: Your doctor will likely order a repeat CBC after 4-6 weeks to ensure the numbers are moving in the right direction.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Interpreting low hemoglobin in your CBC is a vital skill that empowers you to take control of your health. Remember that a low number is a signal, not a final verdict.

- Check the Indices: Always look at the MCV to distinguish between iron deficiency (Microcytic) and vitamin deficiency (Macrocytic).

- Context is Key: A level that is low for a man may be normal for a pregnant woman or a child.

- Symptoms Matter: Pica, restless legs, and shortness of breath are clinical clues that confirm the severity of the lab values.

- Investigate the Root: Whether it is a nutritional gap, a chronic disease, or hidden blood loss, finding the cause is as important as treating the number.

If you see dangerously low hemoglobin results or experience chest pain and extreme weakness, seek immediate medical care. For mild cases, work with your provider to build a plan that includes nutrition, supplementation, and regular monitoring to get your energy back.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What is the fastest way to fix low hemoglobin?

The speed of recovery depends entirely on the underlying cause. For severe iron deficiency anemia, an intravenous (IV) iron infusion is the fastest method to raise levels, often showing significant improvement within 2 weeks. For mild cases, taking oral iron supplements combined with Vitamin C and consuming iron-rich foods like red meat and liver will gradually raise hemoglobin levels over a period of 4 to 8 weeks.

Can low hemoglobin cause a heart attack?

Yes, in severe and untreated cases. When hemoglobin levels are critically low, the heart must pump significantly faster and harder to deliver oxygen to the body. This places immense mechanical strain on the heart muscle. If a person already has underlying heart disease or blocked arteries, this added stress can trigger angina (chest pain) or a heart attack (myocardial infarction) due to the supply-demand mismatch of oxygen.

Why is my hemoglobin low but my iron levels are normal?

This scenario often indicates “Anemia of Chronic Disease” or “Anemia of Inflammation.” Conditions like autoimmune diseases, chronic kidney disease, or chronic infections can prevent your body from utilizing the iron it has stored. It could also indicate a Vitamin B12 or Folate deficiency, or a genetic condition like Thalassemia, rather than iron deficiency anemia.

What level of hemoglobin requires a blood transfusion?

While protocols vary by hospital and patient condition, a hemoglobin level below 7.0 g/dL is the general threshold for transfusion in stable patients. However, doctors may transfuse at higher levels (e.g., 8.0 or 9.0 g/dL) if the patient is actively bleeding, has severe heart disease, or is experiencing severe symptoms like fainting or uncontrolled chest pain.

Does low hemoglobin mean I have cancer?

Not necessarily. While certain cancers (like colon cancer, leukemia, or lymphoma) can cause low hemoglobin, it is far more commonly caused by benign issues like iron deficiency, heavy menstrual periods, or poor diet. However, unexplained anemia, especially in older adults who do not menstruate, should always be investigated thoroughly to rule out gastrointestinal malignancy.

Can dehydration make my hemoglobin look normal when it is actually low?

Yes. Dehydration reduces the volume of plasma (fluid) in your blood, which concentrates the red blood cells. This can artificially elevate your hemoglobin and hematocrit readings, masking an underlying anemia. Once you are rehydrated with fluids, your true, lower levels will be revealed. This phenomenon is known clinically as “hemoconcentration.”

Is it safe to exercise with low hemoglobin?

Light exercise is generally safe, but you should listen to your body carefully. Because your oxygen-carrying capacity is reduced, you will reach exhaustion much faster than usual. High-intensity cardio or endurance training can be dangerous as it places excessive demand on a heart that is already struggling to oxygenate tissues. Always consult your doctor before resuming a training regimen.

How does low hemoglobin affect sleep quality?

Low hemoglobin and low iron stores are strongly linked to Restless Leg Syndrome (RLS) and Periodic Limb Movement Disorder (PLMD). These conditions cause uncomfortable sensations in the legs and involuntary twitching, which disrupt deep sleep cycles and contribute to chronic fatigue and insomnia.

What is the difference between Hemoglobin and Hematocrit?

Hemoglobin is the actual oxygen-carrying protein measured in grams per deciliter (g/dL). Hematocrit is the percentage of your total blood volume that is comprised of red blood cells. They usually rise and fall together. A quick rule of thumb used by doctors is that Hematocrit is typically three times the value of Hemoglobin (e.g., Hgb 10 x 3 = Hct 30%).

Can stress or anxiety cause my hemoglobin to drop?

Psychological stress itself does not directly lower hemoglobin levels. However, chronic stress can lead to physical issues like gastritis or ulcers (causing bleeding) or poor dietary habits, which can secondarily lead to anemia. Conversely, the physical symptoms of anemia (rapid heart rate, shortness of breath, brain fog) can mimic the sensations of an anxiety attack.

Why do doctors check B12 levels for low hemoglobin?

Doctors check Vitamin B12 because a deficiency causes “Macrocytic Anemia.” Without sufficient B12, red blood cells cannot divide properly and become too large and inefficient. This is a common cause of low hemoglobin in vegetarians, vegans, and the elderly who may have trouble absorbing vitamins from food due to gastric issues.

Are there any medications that cause low hemoglobin?

Yes. Certain medications can suppress bone marrow function or cause hemolysis. Common culprits include chemotherapy drugs, certain antibiotics (like cephalosporins), and antiretrovirals. Additionally, frequent use of NSAIDs (like aspirin, ibuprofen, or naproxen) can cause stomach irritation and microscopic bleeding, leading to low hemoglobin over time.

Disclaimer

The content provided in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or CBC test results. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website.

References

- World Health Organization (WHO): Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity.

- Mayo Clinic Laboratories: Hemoglobin, Blood Reference Values.

- American Society of Hematology: Iron-Deficiency Anemia and Anemia of Inflammation.

- National Institutes of Health (NIH): Vitamin B12 Fact Sheet for Health Professionals.