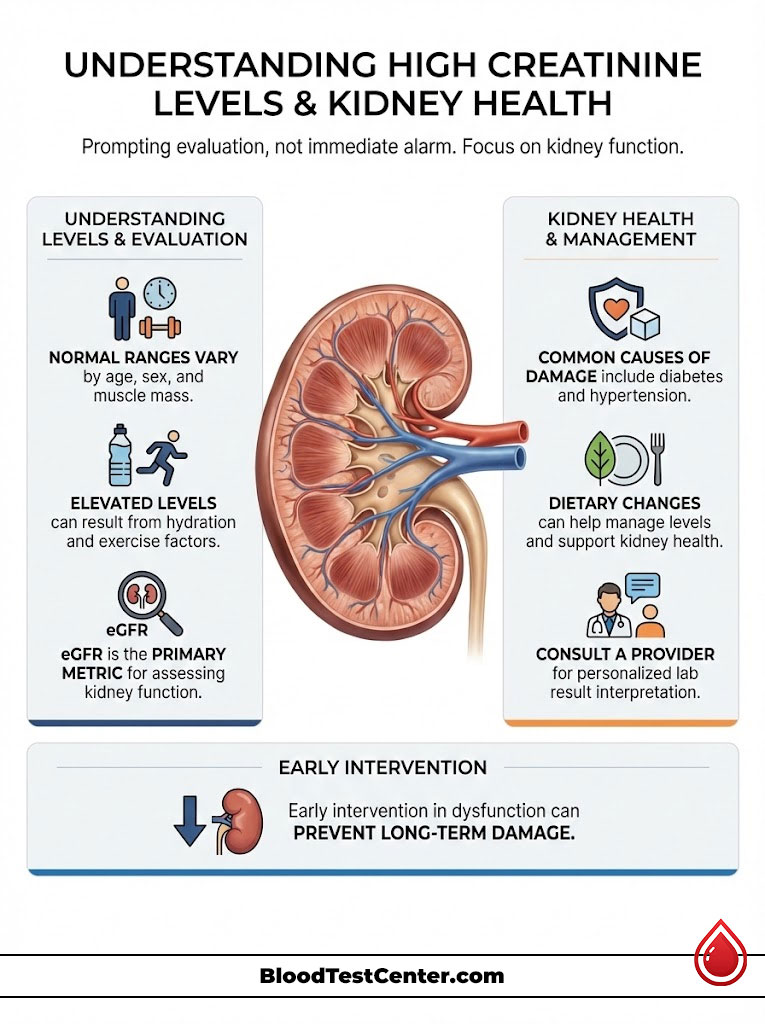

Normal creatinine levels typically range from 0.7 to 1.3 mg/dL for adult males and 0.6 to 1.1 mg/dL for adult females. However, these numbers are relative. A “normal” result for a bodybuilder might be a sign of kidney failure in an elderly patient. Doctors prioritize the Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) over creatinine alone to accurately assess renal health.

Table of Contents

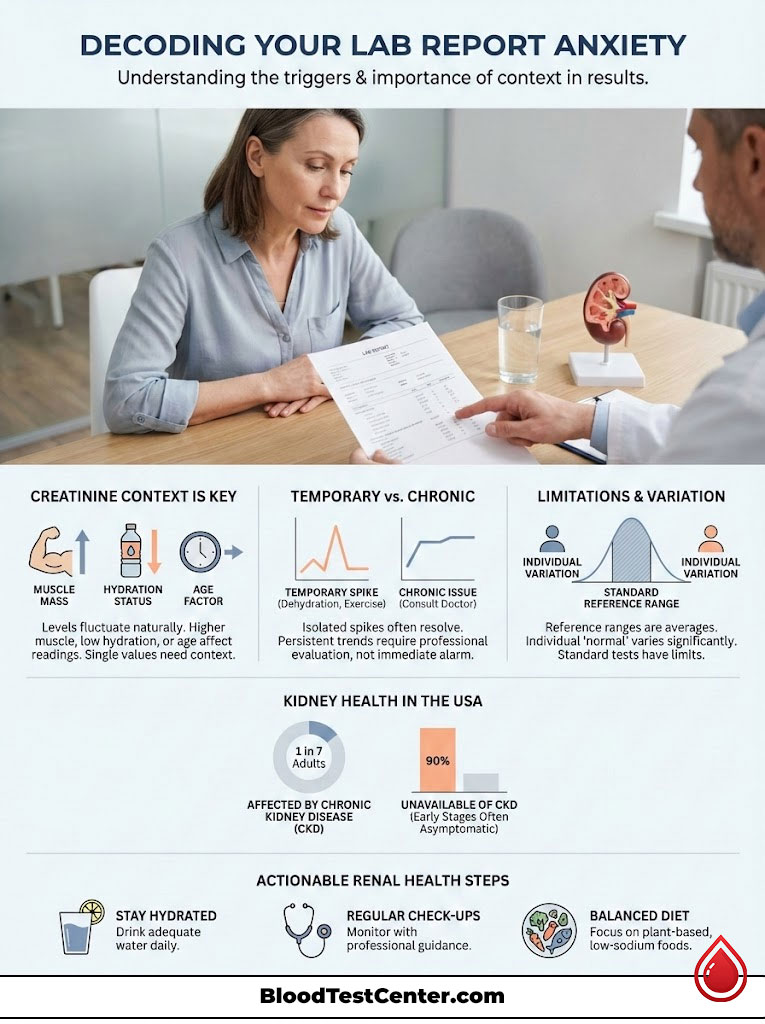

Decoding Your Lab Report Anxiety

Few things trigger immediate medical anxiety like logging into a patient portal. You see a red flag next to a metabolic panel result. You read “Creatinine: High” and your mind races.

You might immediately think of dialysis or transplants. As a nephrologist, I spend a significant portion of my clinical time talking patients off this ledge. While an elevated number demands attention, it is rarely a standalone sentence of doom.

It is simply one data point in a complex physiological story. Normal creatinine levels are not a rigid line in the sand. They fluctuate based on your muscle mass, hydration status, and age.

Even what you ate for dinner last night plays a role. When I review a chart, I do not just look at the creatinine. I look at the patient.

A muscular firefighter and a frail octogenarian should not be held to the same numerical standard. Yet automated lab reports often flag them based on the same generic reference range. This causes unnecessary panic for millions of patients every year.

This article serves as a comprehensive guide to understanding your kidney function. We will move beyond the basic numbers to understand the “why” behind them. We will examine the difference between a temporary spike and chronic disease.

We will also discuss the limitations of standard testing. Finally, we will cover actionable steps you can take to preserve your renal health for decades to come.

Key Statistics: Kidney Health in the USA

- 37 Million: The number of American adults estimated to have Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD); that is more than 1 in 7 people.

- 90%: The percentage of people with early-stage kidney disease who do not know they have it.

- Top 2 Causes: Diabetes and High Blood Pressure are responsible for 75% of all kidney failure cases.

- 1.2 mg/dL: A level that can be normal for a young man but may indicate Stage 3 CKD in an elderly woman.

- 50%: The amount of kidney function you can lose before you feel any physical symptoms.

The Physiology of Creatinine Production

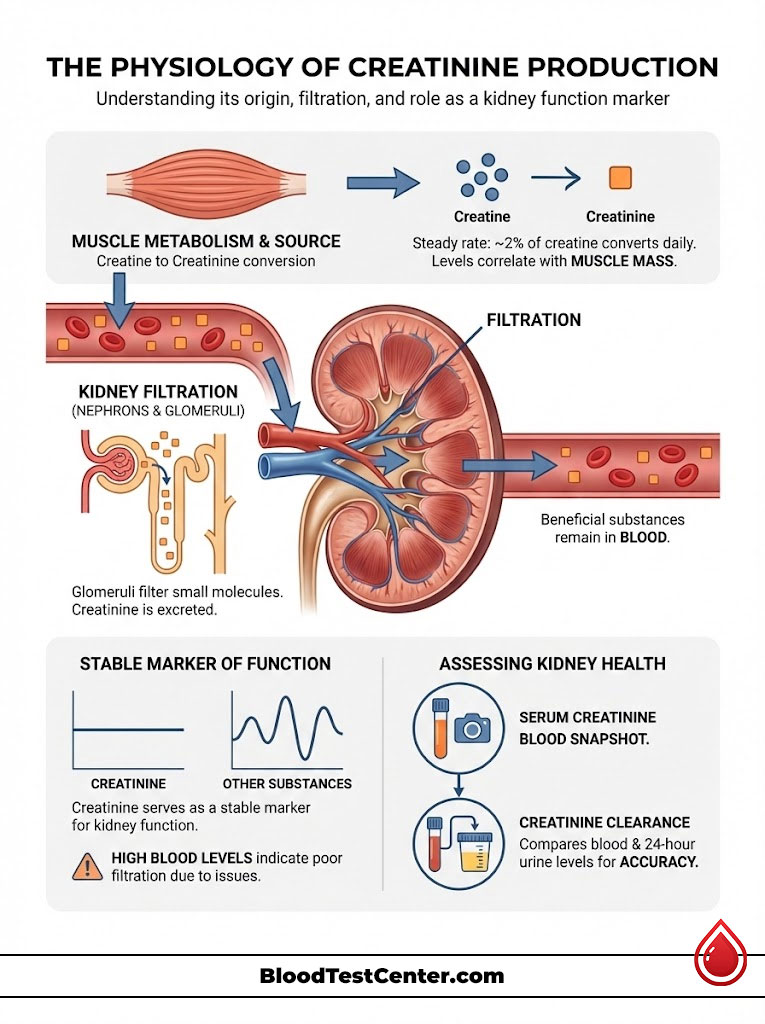

To understand your lab results, you must first understand the source of the chemical being measured. Creatinine is a chemical waste molecule generated from muscle metabolism. It is a byproduct of normal daily activity.

It is produced from creatine, a molecule of major importance for energy production in muscles. Approximately 2% of the body’s creatine is converted to creatinine every day. This production happens at a surprisingly steady rate.

Because it comes from muscle, the amount you have in your blood is directly tied to your physique. A person with 200 pounds of lean muscle produces far more creatinine than a person with 100 pounds of lean muscle. This is the first variable in the equation.

The Kidney’s Filtration System

Your kidneys are sophisticated filtration units containing over a million microscopic filters called nephrons. Within each nephron is a glomerulus. This is a tiny cluster of blood vessels that acts like a sieve.

Because creatinine is a fairly small molecule, it passes freely through the glomerulus. It is not reabsorbed by the kidney tubules to any significant degree. This means that whatever amount your body produces is dumped into the urine.

Think of the kidney as a bouncer at a club. It lets the good stuff (protein, red blood cells) stay in the blood. It kicks the bad stuff (creatinine, urea) out into the urine.

Why We Use It as a Marker

This is why doctors use creatinine as a marker. Unlike other substances that fluctuate wildly based on hormones or circadian rhythms, creatinine production is relatively constant. It acts as a speedometer for your kidneys.

If the kidneys are filtering blood efficiently, creatinine exits the body. Consequently, blood levels remain low. If the filters are clogged or damaged, creatinine builds up in the blood.

When the filters fail, the levels rise. It is an inverse relationship. High blood creatinine equals low kidney function.

Serum Creatinine vs. Creatinine Clearance

There is a distinction between Serum Creatinine and Creatinine Clearance. Serum creatinine is the amount found in the blood sample you gave at the lab. It is a snapshot in time.

Creatinine clearance is a more complex measure. It compares the creatinine level in your blood to the amount in a 24-hour urine collection. This requires you to carry a jug around for a day.

While serum creatinine is the standard screening tool, clearance tests provide a more precise look. We use clearance when the blood test is ambiguous. It tells us exactly how much blood your kidneys clean per minute.

Normal Creatinine Levels: Detailed Reference Ranges

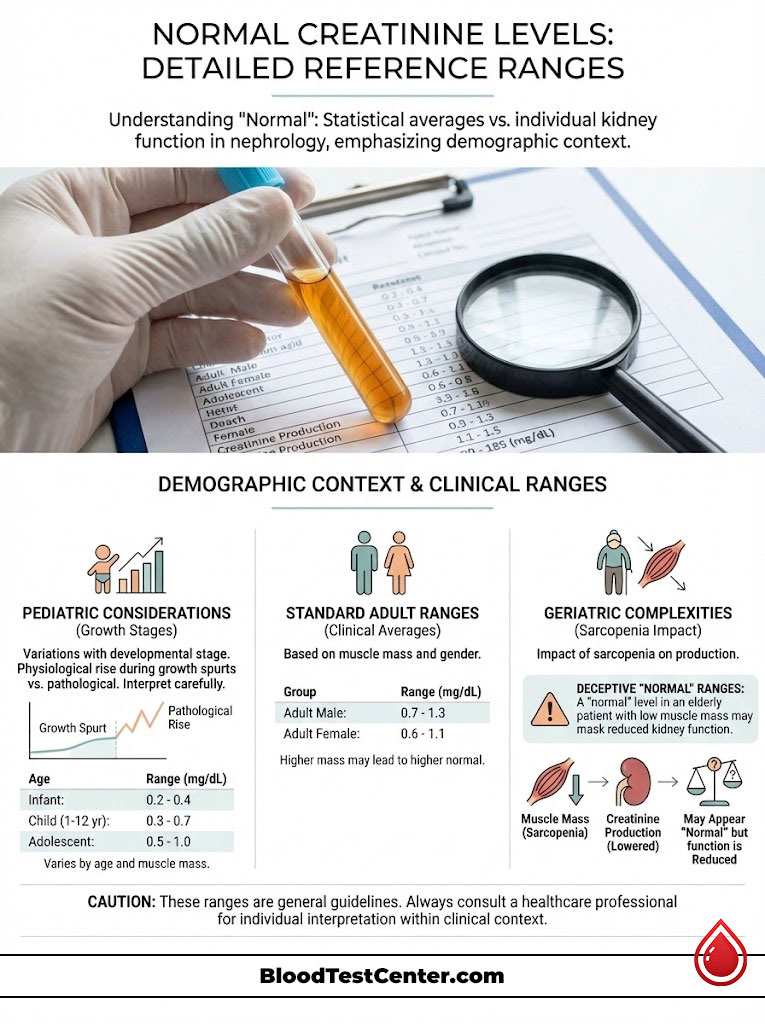

The term “normal” is dangerous in nephrology because it implies a universal standard that does not exist. However, laboratories must use statistical averages to create reference ranges. These ranges generally encompass 95% of the healthy population.

It is vital to look at where you fit within these demographics. Being at the top of the range is fine for some. It is dangerous for others.

Standard Clinical Ranges for Adults

- Adult Males: 0.7 to 1.3 mg/dL. Men typically have higher normal creatinine levels because they generally possess more skeletal muscle mass than women. Testosterone drives muscle growth, which drives creatinine production.

- Adult Females: 0.6 to 1.1 mg/dL. Women usually have lower muscle mass and thus a lower baseline production rate. Hormonal differences also play a role in renal blood flow.

- Pregnancy: Levels actually drop during pregnancy. The kidneys hyper-filter to clean the baby’s blood too. A level of 0.8 mg/dL might be flagged as high for a pregnant woman.

Pediatric and Geriatric Considerations

Children: 0.2 to 1.0 mg/dL. This varies heavily by developmental stage. An infant will have much lower levels than a teenager.

Pediatric nephrologists use height-based formulas to determine safety. A teenager going through a growth spurt may see a rapid rise in creatinine. This is usually physiological, not pathological.

The Elderly: This is the most complex category. Seniors often lose muscle mass, a condition known as sarcopenia. Therefore, they produce less creatinine.

A “normal” looking result of 1.0 mg/dL in an 85-year-old woman might actually mask significant kidney dysfunction. Her production is so low that even a failing kidney can clear it. We call this the “blind spot” of creatinine testing.

Comparison Table: Creatinine Reference Ranges by Demographic

| Demographic Group | Normal Range (mg/dL) | Clinical Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Adult Men (18-60) | 0.7 – 1.3 | Higher upper limit due to testosterone-driven muscle mass. Bodybuilders may naturally test above 1.3 without renal injury. |

| Adult Women (18-60) | 0.6 – 1.1 | Lower baseline. Pregnancy can temporarily lower these numbers further due to hyperfiltration. |

| Children (3-18) | 0.5 – 1.0 | Highly dependent on growth spurts. Pediatric nephrologists use height-based formulas for accuracy. |

| Infants (< 3 years) | 0.2 – 0.5 | Very low muscle mass results in very low baseline creatinine. |

| Elderly (60+) | 0.6 – 1.2 | WARNING: “Normal” ranges are deceptive here. Sarcopenia (muscle loss) lowers production, masking reduced kidney function. |

The Critical Context: eGFR and Muscle Mass

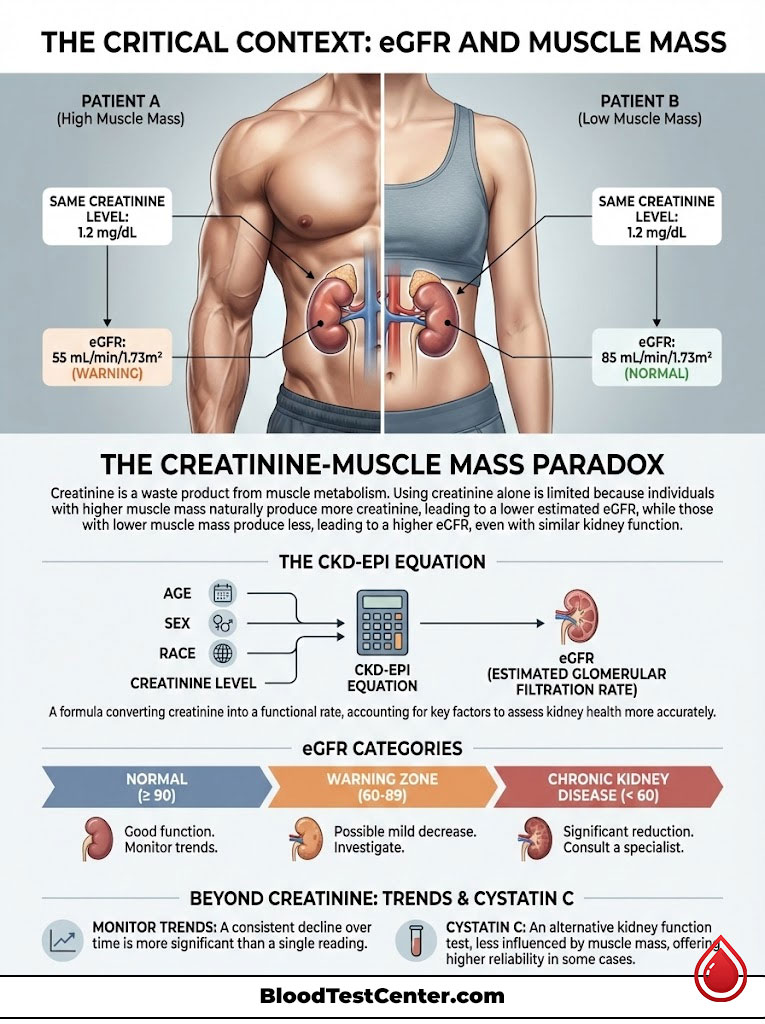

Relying solely on creatinine is a flaw in general practice medicine. We must convert that raw number into a functional rate. This is where the Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) comes into play.

The eGFR is the gold standard for staging kidney disease. It translates the abstract creatinine number into a percentage of function. It answers the question: “How well are my kidneys working?”

The Flaw of Creatinine Alone

Imagine two patients sitting in a waiting room. Patient A is a 25-year-old NFL linebacker. Patient B is a 75-year-old grandmother.

Both have a creatinine level of 1.3 mg/dL. For the linebacker, this is perfect health. His high muscle mass churns out creatinine, and his kidneys are clearing it efficiently.

For the grandmother, 1.3 mg/dL likely represents Stage 3 Chronic Kidney Disease. Her low muscle mass should produce a level of 0.6 mg/dL. The fact that it is 1.3 means her kidneys are struggling to clear even that small amount.

The Math Behind the Medicine: CKD-EPI

To solve this, we use the CKD-EPI Equation. This formula takes the serum creatinine and adjusts it for age, gender, and race. It calculates the estimated filtration percentage.

An eGFR above 90 is considered normal. An eGFR between 60 and 89 is a warning zone. An eGFR below 60 for three months indicates Chronic Kidney Disease.

We look for trends rather than single numbers. A drop from 90 to 85 is usually noise. A drop from 60 to 45 is a clinical event.

Expert Insight: The Cystatin C Tie-Breaker

If your doctor is unsure if your creatinine is high due to muscle or kidney failure, ask for a Cystatin C test. Cystatin C is a protein produced by all cells in the body, not just muscle. It is not influenced by how much you bench press or how much muscle you have lost. If your creatinine is high but your Cystatin C is normal, your kidneys are likely fine. This test is the ultimate truth-teller in nephrology.

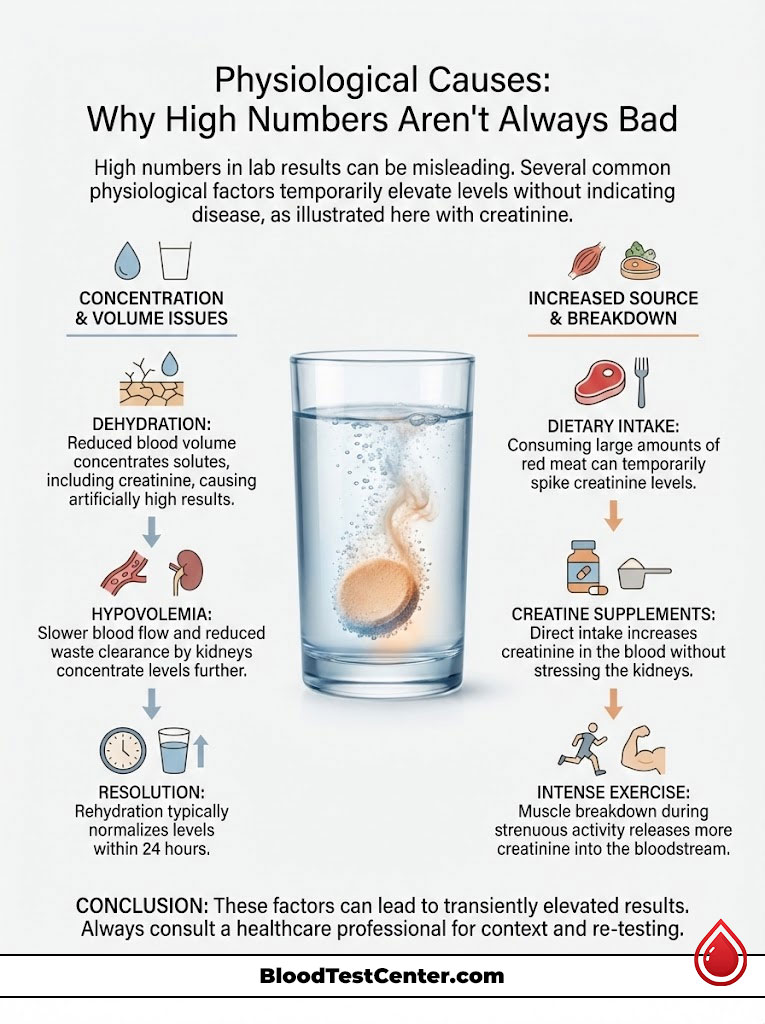

Physiological Causes: Why High Numbers Aren’t Always Bad

Not every high number equals a diseased organ. Several non-medical factors can temporarily spike your levels. We call these “physiological” causes.

In these cases, the kidney machinery is working fine. The input data is just skewed. It is vital to rule these out before assuming disease.

Dehydration and Hypovolemia

What causes high creatinine in blood most frequently? Often, it is simple dehydration. When you are dehydrated, your blood volume drops.

This state is called hypovolemia. It concentrates the blood, making all solute levels appear higher. The kidneys also aggressively hold onto water and sodium to maintain blood pressure.

This survival mechanism inadvertently slows down the clearance of waste products. Rehydrating often returns these levels to baseline within 24 hours. This is the most common reason for a “false alarm.”

Dietary Intake: The “Cooked Meat” Effect

Creatinine is formed from creatine. Creatine is found in high concentrations in red meat. If you consume a large steak or a burger within 12 to 24 hours of your blood draw, your blood absorbs it.

Your gut absorbs the creatinine from the cooked meat directly into your bloodstream. This can artificially raise your level by 0.1 to 0.2 mg/dL. This small bump can push you out of the “normal” range.

We often advise patients with borderline results to avoid red meat the night before a re-test. Stick to plant-based meals or fish before your annual physical.

Supplements and Exercise

The use of Creatine Monohydrate is rampant in the fitness community. It is a safe and effective supplement for muscle growth. However, when you take creatine supplements, you are loading your body with the precursor to creatinine.

Naturally, your blood levels will rise. This is a “false positive” for kidney stress. The kidneys are filtering normally; there is simply more waste to filter.

Similarly, intense exercise breaks down muscle tissue. This releases creatinine into the bloodstream. A blood test taken after a marathon or heavy leg day will almost always show elevated numbers.

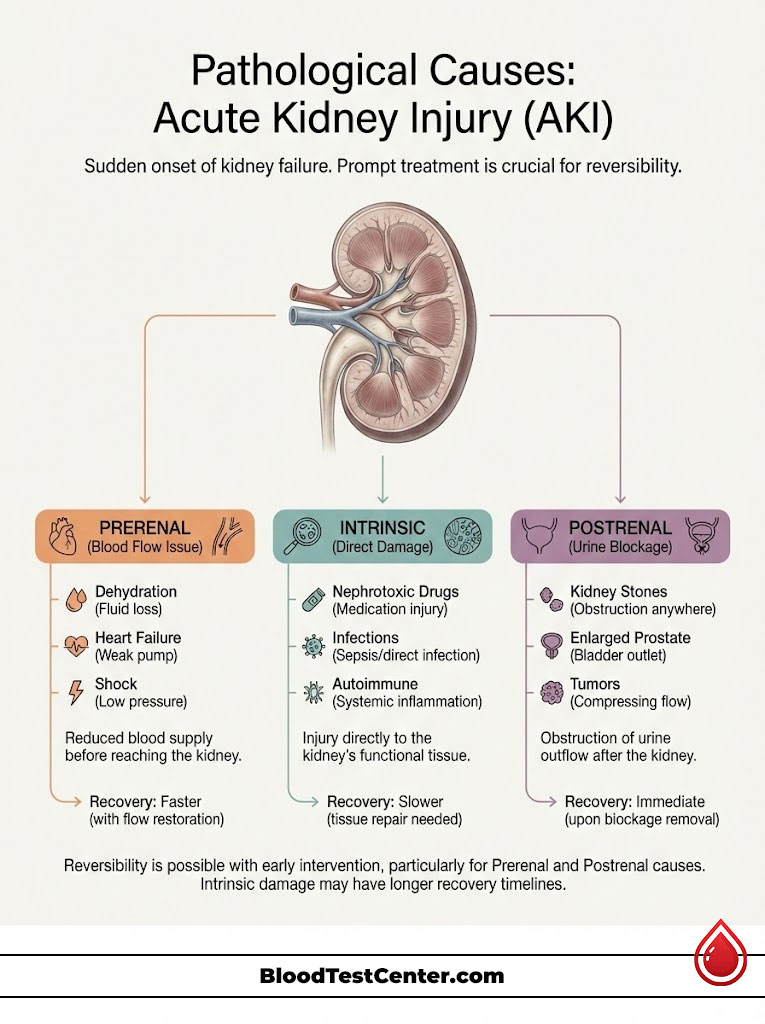

Pathological Causes: Acute Kidney Injury (AKI)

When physiological causes are ruled out, we must investigate pathological triggers. We categorize kidney issues into two main buckets: Acute and Chronic. Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) is a sudden attack.

AKI happens within a few hours or a few days. It is often reversible if treated quickly. We classify AKI based on where the problem originates.

Prerenal AKI: The Plumbing Issue

This is the most common form of AKI. “Prerenal” means “before the kidney.” There is nothing wrong with the kidney itself.

The problem is a lack of blood flow. If the kidney doesn’t get blood, it can’t filter. This happens during severe dehydration, heart failure, or shock.

It also happens with blood loss from trauma. Once blood flow is restored, the creatinine usually drops back to normal. It is a supply chain issue.

Intrinsic AKI: The Damage Within

This type involves direct damage to the kidney tissue. The filters or the tubes are injured. Common culprits include nephrotoxic drugs.

Certain antibiotics (like Vancomycin) and NSAIDs (like Ibuprofen) can be toxic. Contrast dye from CT scans can also cause this in vulnerable patients. Infections like sepsis can attack the kidney cells directly.

Autoimmune diseases like Lupus can also cause intrinsic damage. Recovery from this type of injury is slower and sometimes incomplete.

Postrenal AKI: The Blockage

“Postrenal” means “after the kidney.” This is a plumbing blockage downstream. The kidneys are filtering fine, but the urine has nowhere to go.

This back-pressure damages the kidneys. Common causes include kidney stones lodged in the ureter. In men, an enlarged prostate is a frequent cause.

Tumors in the bladder or cervix can also cause obstructions. Removing the blockage usually resolves the creatinine spike immediately.

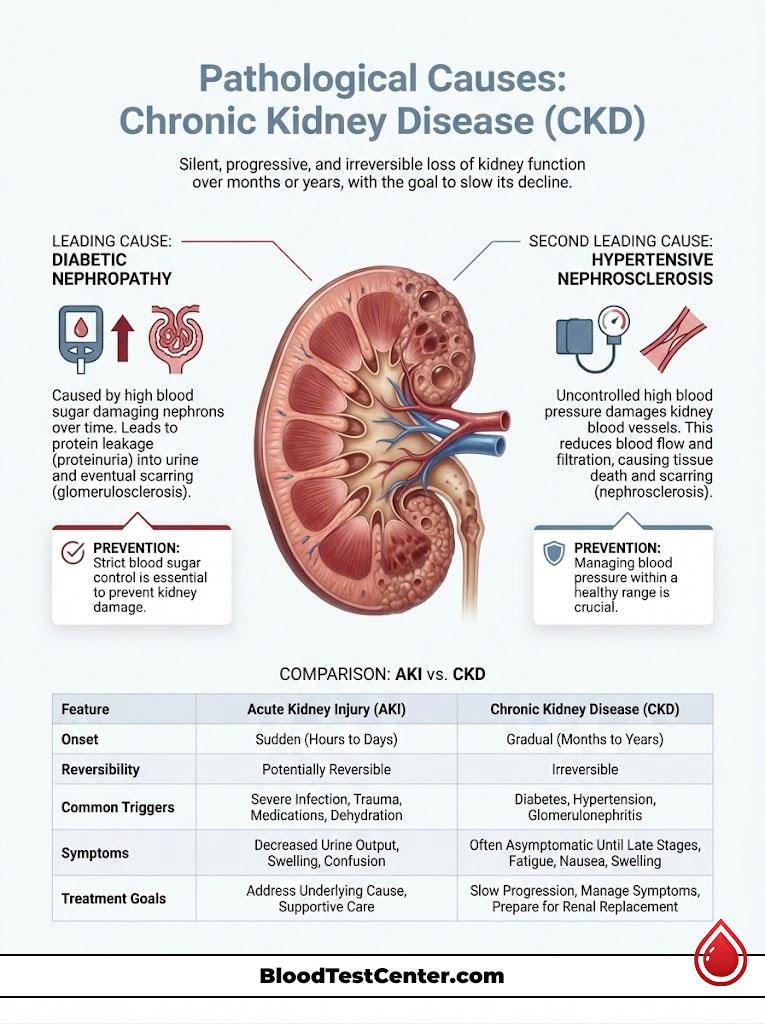

Pathological Causes: Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

Unlike AKI, Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is silent and progressive. It is the gradual loss of kidney function over time. Normal creatinine levels slowly creep up over years.

The damage is usually irreversible. The goal of treatment is to slow the decline. The two primary drivers of CKD in the United States are responsible for the vast majority of cases.

Diabetic Nephropathy

Diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure. High blood sugar acts like a slow poison to the nephrons. It damages the tiny blood vessels inside the filters.

Over time, the filters become leaky. They start spilling protein into the urine. Eventually, they scar over and stop working entirely.

Strict blood sugar control is the only way to prevent this. Once the scarring happens, it cannot be undone.

Hypertensive Nephrosclerosis

High blood pressure is the second leading cause. The kidneys are vascular organs; they are full of blood vessels. Uncontrolled pressure hammers these delicate vessels.

Imagine a fire hose connected to a garden sprinkler. The high pressure destroys the sprinkler heads. The kidney vessels thicken and narrow to protect themselves.

This reduces blood flow and filtration. It becomes a vicious cycle: damaged kidneys raise blood pressure further, which causes more damage.

Comparison Table: Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) vs. Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)

| Feature | Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) | Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) |

|---|---|---|

| Onset Time | Sudden (Hours to Days) | Gradual (Months to Years) |

| Reversibility | Often Reversible with prompt treatment | Irreversible (Progressive) |

| Common Triggers | Dehydration, Nephrotoxic drugs, Obstruction | Diabetes, Hypertension, Glomerulonephritis |

| Symptoms | Sudden drop in urine output, confusion, chest pain | Often asymptomatic until advanced stages |

| Treatment Goal | Restore function to baseline | Slow progression and preserve remaining function |

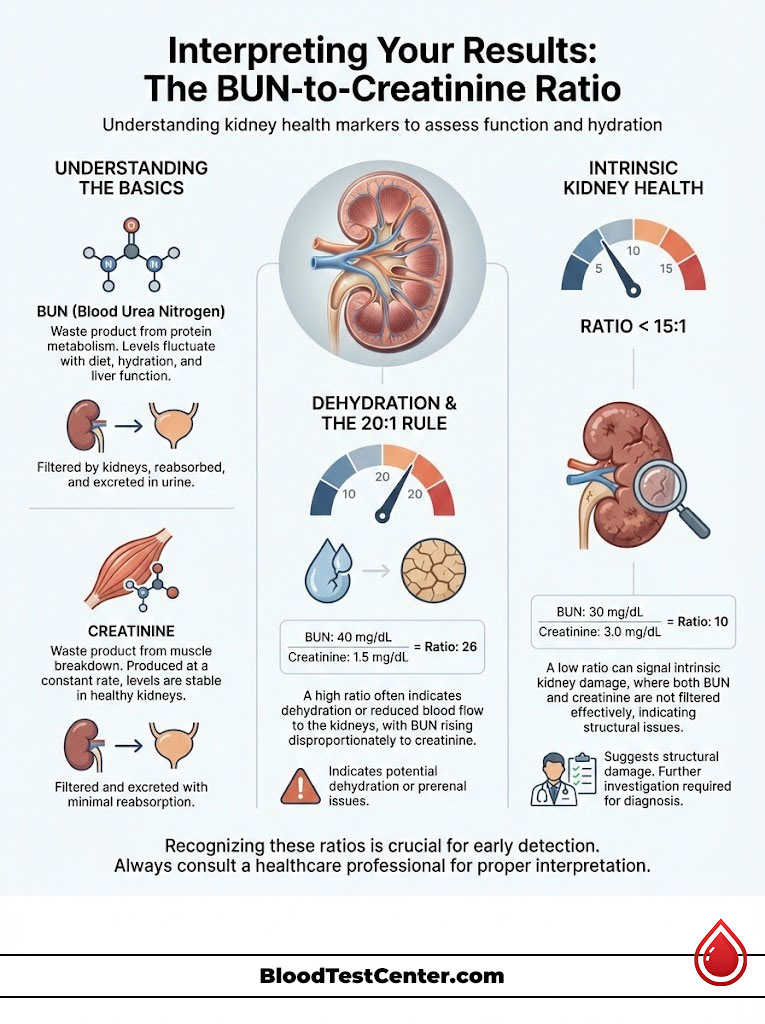

Interpreting Your Results: The BUN-to-Creatinine Ratio

Doctors look for clues to distinguish between dehydration and actual kidney damage. One of the best clues is the BUN to creatinine ratio. BUN stands for Blood Urea Nitrogen.

Like creatinine, BUN is a waste product. However, the kidney handles it differently. The kidney can reabsorb BUN back into the blood, but it cannot reabsorb creatinine.

The 20:1 Rule (Prerenal)

When you are dehydrated, your kidneys try to save water. In doing so, they also pull BUN back into the blood. Creatinine, however, still gets filtered out.

This causes the BUN to rise much faster than the creatinine. If your ratio is greater than 20:1, the cause is likely dehydration. For example, a BUN of 40 and a Creatinine of 1.5 gives a ratio of 26.

This suggests the kidney structure is intact. It is just thirsty. This is a “Prerenal” pattern.

The < 15:1 Rule (Intrinsic)

If the kidney is damaged, it cannot reabsorb BUN effectively. Both BUN and Creatinine rise together in a locked step. The ratio stays closer to 10:1 or 15:1.

If your BUN is 30 and your Creatinine is 3.0, the ratio is 10. This suggests “intrinsic” kidney damage. The kidney itself is injured.

This pattern prompts us to look for diseases like glomerulonephritis or toxin exposure. It is a red flag for structural damage.

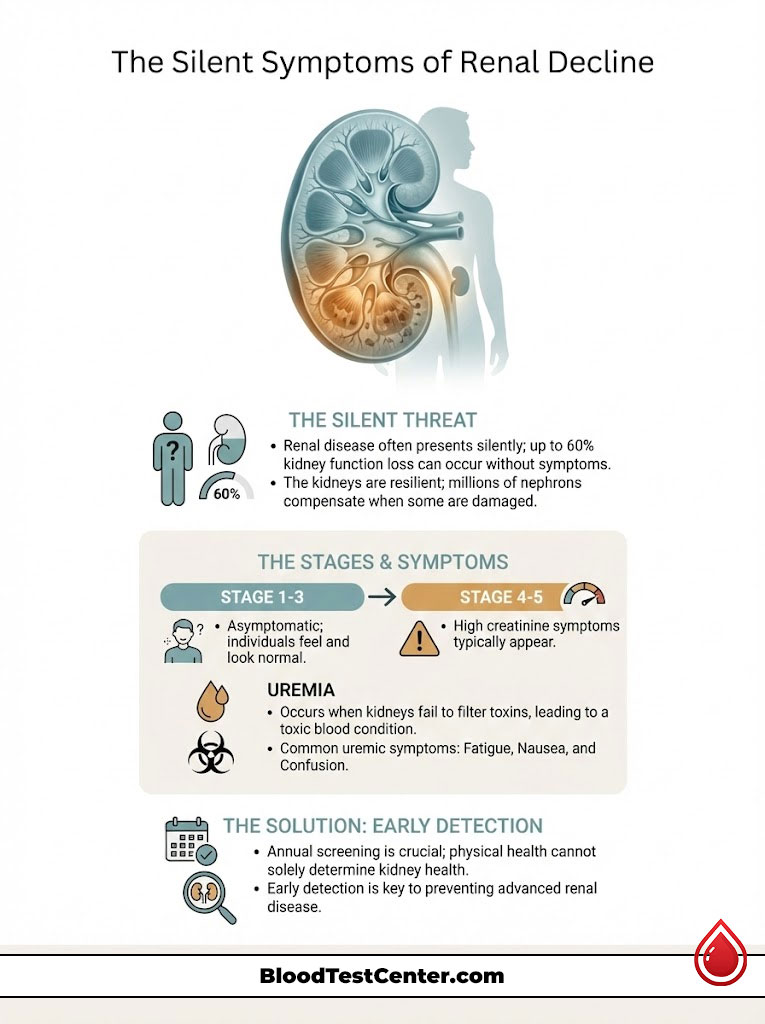

The Silent Symptoms of Renal Decline

One of the most dangerous aspects of renal disease is its silence. You can lose up to 60% of your kidney function before you feel anything different. The kidneys are incredibly redundant organs.

You have millions of nephrons. When some die, the others work harder to pick up the slack. High creatinine symptoms usually only manifest when the condition has advanced to Stage 4 or 5.

Early Stages: The Asymptomatic Phase

In Stages 1 through 3, there are typically no physical symptoms. You feel normal. You look normal. The urine looks normal.

The only warning sign is the number on the lab report. This is why annual screening is vital. We cannot rely on how you feel to diagnose kidney disease.

Advanced Stages: Uremic Symptoms

When the kidneys fail to filter toxins, a condition called uremia sets in. The blood becomes toxic. Symptoms include:

- Edema: Swelling in the legs, ankles, or around the eyes. This is due to fluid retention and sodium handling issues.

- Changes in Urination: Foamy urine indicates protein leakage. Bloody urine indicates structural damage. A significant decrease in urine volume is a late sign.

- Constitutional Symptoms: Severe fatigue is common due to anemia. Nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite occur as toxins build up in the gut.

- Metallic Taste: Many patients report a distinct “metallic” or ammonia taste in the mouth. This is literally the taste of urea in the saliva.

- Pruritus: This is intense itching caused by high phosphorus levels. The phosphorus deposits in the skin, causing an itch that cannot be scratched away.

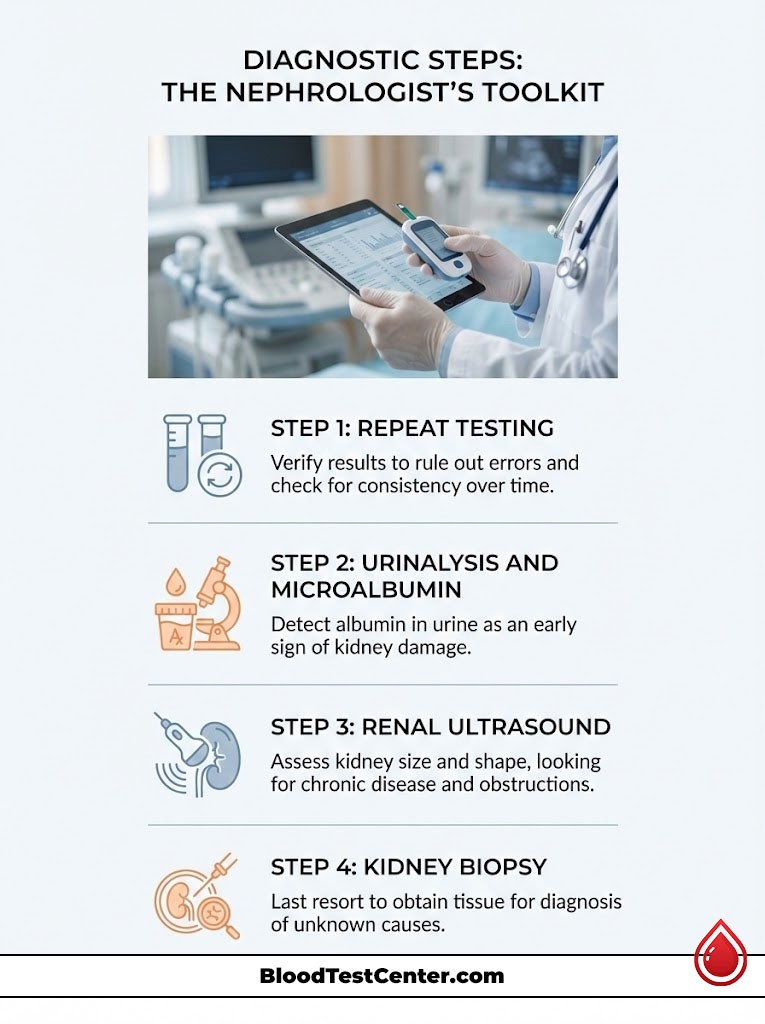

Diagnostic Steps: The Nephrologist’s Toolkit

If your kidney function test comes back abnormal, do not panic. The clinical workflow usually follows a specific path to verify the data. We do not diagnose based on one number.

Step 1: Repeat Testing

We almost always repeat the labs. We need to ensure the first result wasn’t a lab error. We also need to rule out a dehydrated afternoon.

We look for consistency. Is the number persistently high? Or was it a one-time fluke?

Step 2: Urinalysis and Microalbumin

We check the urine for albumin. Albumin is a protein. It is large and should stay in the blood.

If it is in the urine, the filter is damaged. The presence of protein is often the first sign of diabetic kidney disease. It appears long before the creatinine rises.

Step 3: Renal Ultrasound

This imaging test looks at the size and shape of the kidneys. It is non-invasive. We look for two things: size and obstruction.

Small, shrunken kidneys suggest chronic disease and scarring. Normal-sized kidneys might suggest an acute issue. We also look for hydronephrosis, which is swelling caused by a blockage.

Step 4: Kidney Biopsy

This is the final resort. In rare cases where the cause is unknown, we need tissue. A nephrologist uses a needle to take a tiny sample of the kidney.

We examine the tissue under a microscope. This tells us exactly what is attacking the kidney. It guides our treatment plan for autoimmune diseases.

How to Lower Creatinine Levels: Medical Strategy

Patients frequently ask how to lower creatinine levels naturally. The honest medical answer is that you do not treat the number. You treat the underlying cause.

Lowering the number artificially without fixing the kidney does not help. It is like putting tape over the check engine light. However, specific strategies can preserve function.

Hydration Protocols

If the cause is dehydration, drinking water will lower the levels. It restores volume and flow. However, balance is key.

In advanced kidney failure, the kidneys cannot excrete water efficiently. Drinking gallons of water in an attempt to “flush” the kidneys can be fatal. It can lead to fluid overload and heart failure.

Always follow your doctor’s fluid restriction guidelines if you have advanced CKD. More is not always better.

Medication Management

We use specific drugs to protect the kidneys. These are known as renoprotective agents. ACE inhibitors (like Lisinopril) and ARBs (like Losartan) are the first line of defense.

They lower the pressure inside the tiny filters of the kidney. While they might cause a tiny, temporary bump in creatinine initially, they preserve function over the long term. They are kidney bodyguards.

A new class of drugs called SGLT2 inhibitors is revolutionizing care. Originally for diabetes, they have shown incredible ability to stop kidney disease progression in non-diabetics too.

Avoiding Nephrotoxins

You must play defense. Avoid substances that hurt the kidneys. NSAIDs like Ibuprofen, Naproxen, and high-dose Aspirin are notorious.

They constrict blood flow to the kidneys. Taken chronically, they cause significant damage. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is generally a safer alternative for pain in kidney patients.

Also, be wary of herbal supplements. Many are unregulated and contain heavy metals or aristolochic acid, which is toxic to kidneys.

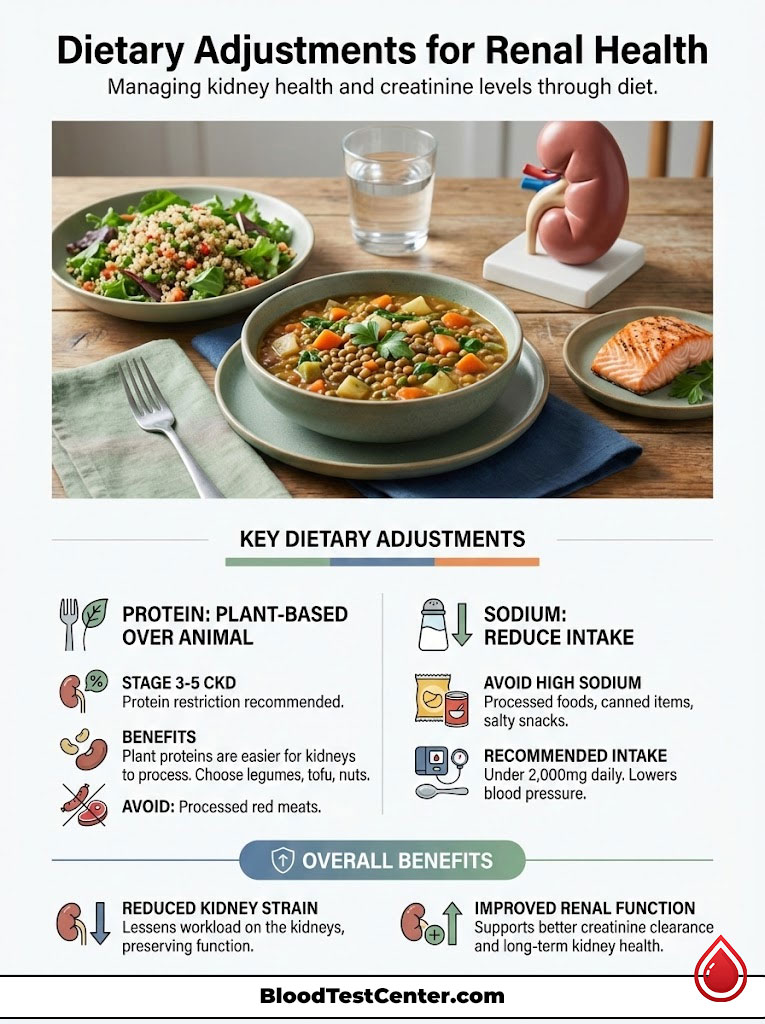

Dietary Adjustments for Renal Health

Diet is a powerful tool in managing creatinine and kidney health. However, the “Renal Diet” is complex. It changes depending on your stage of disease.

Protein Restriction

The breakdown of protein creates nitrogenous waste. This includes urea and creatinine. For patients with Stage 3-5 CKD, we often recommend limiting protein intake.

This reduces the workload on the kidneys. It is like taking a heavy backpack off the kidney’s shoulders. However, you must avoid malnutrition.

The source of protein matters. Emerging research suggests that plant-based proteins put less stress on the kidneys than animal proteins. They produce fewer acidic waste products.

The Plant-Based Advantage

Foods to avoid with high creatinine often include processed red meats. These are high in sodium, phosphate, and protein. Plant-based diets are becoming the standard of care.

Fruits, vegetables, and grains are easier for the kidneys to process. They also help combat metabolic acidosis, a condition common in kidney disease.

Sodium and Pressure

Reducing sodium is non-negotiable. High salt intake raises blood pressure. As we discussed, high blood pressure destroys kidney tissue.

The average American eats over 3,400mg of sodium a day. A kidney patient should aim for under 2,000mg. This single change can significantly lower blood pressure and protect renal function.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Receiving a lab report with “High Creatinine” is a call to action. It is not necessarily a diagnosis of doom. Remember that normal creatinine levels are highly individual.

A number that is normal for a young athlete may be abnormal for an older adult. The context of muscle mass, hydration, and age is paramount. You must look at the whole picture.

The most accurate way to assess your kidney health is through the Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR). When in doubt, ask for Cystatin C testing. This eliminates the muscle mass variable.

If your levels are truly elevated due to kidney dysfunction, early intervention is key. Blood pressure control, diabetes management, and dietary changes can preserve your kidney function for decades.

The kidneys are resilient organs. They are designed to last a lifetime. With the right care and early detection, they can serve you well into old age.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the normal creatinine levels for adult men and women?

Standard reference ranges for serum creatinine are typically 0.7 to 1.3 mg/dL for men and 0.6 to 1.1 mg/dL for women. These values differ because creatinine is a byproduct of muscle metabolism, and men generally possess higher skeletal muscle mass driven by testosterone. However, these numbers must always be interpreted in the context of your specific age and physical build.

Why is my eGFR more important than my serum creatinine number?

The estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate (eGFR) is the gold standard for assessing renal health because it translates your creatinine level into a functional percentage. While creatinine is just a raw waste marker influenced by muscle mass, eGFR adjusts for age, gender, and race to tell us exactly how well your nephrons are filtering blood. A “normal” creatinine can mask significant disease in a small, elderly patient, which the eGFR calculation will accurately reveal.

Can intense exercise or a high-protein diet cause a temporary spike in creatinine?

Yes, both can cause physiological spikes that do not indicate kidney disease. Intense resistance training breaks down muscle tissue, releasing extra creatinine into the blood, while consuming cooked red meat or creatine supplements provides a direct exogenous source of the molecule. We often advise patients to avoid heavy exercise and red meat for 24 hours before a metabolic panel to ensure the most accurate baseline.

What are the early warning signs and symptoms of high creatinine?

In the early stages (Stages 1-3), kidney disease is typically “silent” and asymptomatic. Physical symptoms like edema (swelling), foamy urine (proteinuria), and fatigue usually only appear once function has dropped significantly. By the time you experience a metallic taste or pruritus (itching), the kidneys are often struggling to clear uremic toxins from the bloodstream.

How does dehydration affect my kidney function test results?

Dehydration causes hypovolemia, which reduces blood flow to the kidneys and concentrates waste products in the blood. This can lead to a “prerenal” elevation in creatinine, where the kidney structure is healthy but lacks the fluid volume to filter efficiently. Once the patient is properly rehydrated, these levels typically return to their normal baseline within a day or two.

What is the difference between Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) and Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD)?

AKI is a sudden, rapid decline in function occurring over hours or days, often due to dehydration, infection, or medication toxicity; it is frequently reversible if the underlying cause is treated. CKD is a gradual, progressive loss of function over months or years, usually driven by diabetes or hypertension. Unlike AKI, the damage in CKD is generally irreversible, and the clinical goal is to preserve the remaining nephron function.

Why might a “normal” creatinine level be misleading for elderly patients?

Seniors often experience sarcopenia, or age-related muscle loss, which results in very low natural creatinine production. Because they produce so little waste, a “normal” lab result of 1.0 mg/dL might actually indicate significant Stage 3 kidney disease. In geriatric nephrology, we rely much more heavily on eGFR and Cystatin C to avoid missing a diagnosis of renal decline.

What does a high BUN-to-creatinine ratio indicate about my health?

A BUN-to-creatinine ratio higher than 20:1 is a classic clinical indicator of a “prerenal” issue, most commonly dehydration or heart failure. This happens because the kidneys reabsorb urea back into the blood when they are trying to conserve water, while creatinine continues to be excreted. A lower ratio (10:1) suggests “intrinsic” damage, meaning the problem lies within the kidney’s filtration units themselves.

When should I ask my doctor for a Cystatin C test?

You should request a Cystatin C test if your creatinine-based eGFR is borderline or if you have an unusual body composition, such as being a bodybuilder or extremely frail. Cystatin C is a protein produced by all nucleated cells at a constant rate and is not affected by muscle mass, diet, or exercise. It serves as a highly accurate “tie-breaker” to determine if an elevated creatinine is a false alarm or true kidney dysfunction.

Which common medications can cause nephrotoxicity and raise creatinine?

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like Ibuprofen (Advil/Motrin) and Naproxen (Aleve) are common culprits because they constrict the blood vessels entering the kidney. Other nephrotoxic risks include certain antibiotics like Vancomycin and IV contrast dyes used in medical imaging. If you have known kidney issues, Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is generally the safer choice for pain management.

How can I lower my creatinine levels naturally through dietary changes?

While you cannot “cure” damaged kidneys, you can lower creatinine levels by reducing the workload on the organ. This includes adopting a plant-dominant diet, which produces less nitrogenous waste than animal proteins, and strictly limiting sodium to under 2,000mg per day to manage blood pressure. Proper hydration is essential, but patients with advanced CKD must follow their nephrologist’s specific fluid volume guidelines.

What are the primary causes of long-term kidney damage in the United States?

Diabetes and high blood pressure (hypertension) are the “Big Two” causes, responsible for approximately 75% of all kidney failure cases. High blood sugar damages the delicate microvasculature of the nephrons, while high blood pressure causes physical scarring of the renal blood vessels. Managing these two conditions through medication and lifestyle is the most effective way to prevent the progression of Chronic Kidney Disease.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The interpretation of laboratory results is complex and must be performed by a qualified healthcare professional who can consider your full clinical history. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay seeking it because of something you have read in this article.

References

- National Kidney Foundation (NKF) – kidney.org – Comprehensive clinical guidelines on Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) and eGFR calculation.

- American Journal of Kidney Diseases – ajkd.org – Research study on the CKD-EPI equation and the accuracy of creatinine-based filtration estimates.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) – cdc.gov/kidneydisease – Official statistics on the prevalence of kidney disease in the United States.

- Mayo Clinic – mayoclinic.org – Clinical overview of creatinine tests, normal ranges, and causes of abnormal results.

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) – niddk.nih.gov – Educational resources on diabetic nephropathy and hypertensive kidney damage.