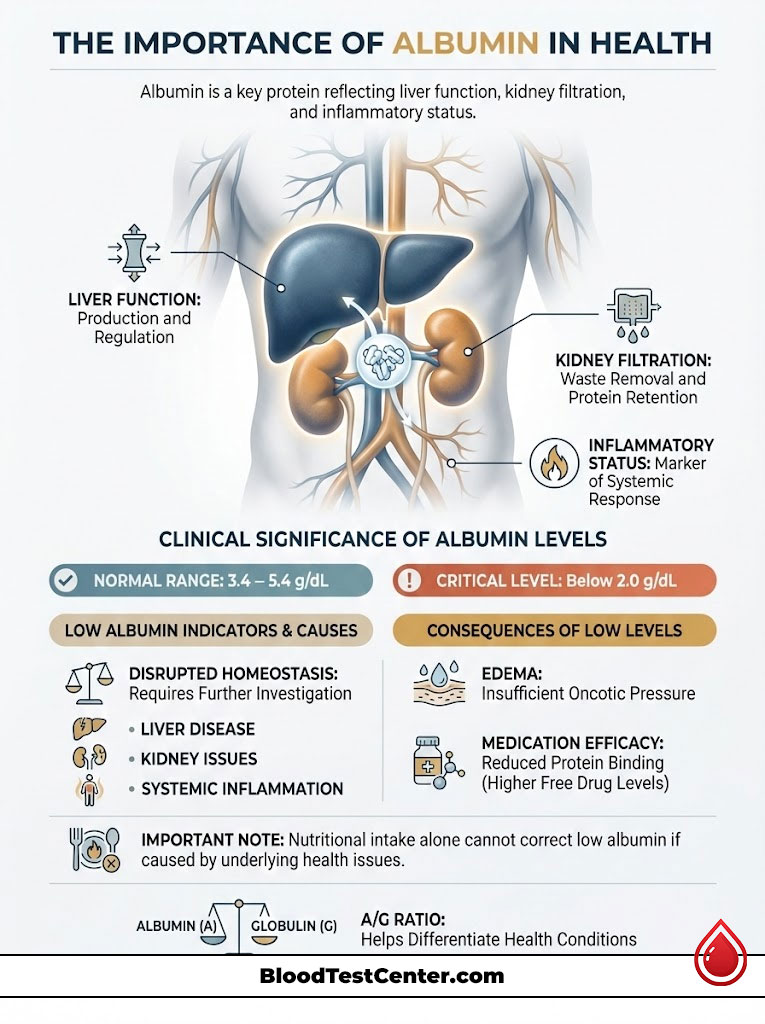

Low albumin, medically termed hypoalbuminemia, is rarely a disease itself. It’s a loud signal of an underlying physiological problem. It typically points to one of three specific mechanisms: your liver isn’t manufacturing enough protein (due to cirrhosis or genetic issues), your kidneys or gut are leaking protein (nephrotic syndrome or malabsorption), or your body is battling significant inflammation (infection, trauma, or chronic disease). An isolated low result mandates a full evaluation of liver enzymes, kidney filtration rates, and inflammatory markers to identify the root cause.

Table of Contents

When I review a patient’s Comprehensive Metabolic Panel (CMP), my eyes often scan past the glucose and electrolytes to land on a specific number: albumin. To the untrained eye, it’s just another protein on a long list of medical jargon. To a clinical pathologist or an attending physician, it’s the body’s silent messenger.

It tells us about the integrity of your blood vessels. It reveals the functional capacity of your liver. It even hints at the current state of your immune system.

You’re likely reading this because you saw a number on a lab report that fell below the standard reference range. Naturally, the first instinct is to panic about liver failure. While the liver is the factory that produces this protein, the answer to what does low albumin in a blood test really mean is far more nuanced.

It involves a complex interplay between the kidneys, the gastrointestinal tract, and the body’s inflammatory response. We need to look at the whole picture.

Albumin is the most abundant protein in your blood plasma. Its primary job is maintaining colloid oncotic pressure. This is essentially the force that keeps fluids inside your blood vessels rather than leaking into your tissues. When these levels drop, the consequences are systemic.

We see fluid retention. We see altered drug efficacy. We see compromised transport of vital hormones.

In this comprehensive analysis, we’ll walk through the physiology of this vital protein. We’ll dissect the three primary mechanisms of its decline. Finally, we’ll explain the diagnostic algorithm we use to differentiate between a kidney issue, a liver issue, or a simple inflammatory response.

Key Statistics & Data Points

- Standard Range: 3.4 to 5.4 g/dL (34 to 54 g/L).

- Critical Level: Levels below 2.0 g/dL are associated with a significant increase in mortality rates for hospitalized patients.

- Synthesis Rate: A healthy liver produces approximately 10 to 15 grams of albumin daily.

- Circulating Pool: Albumin constitutes about 50% to 60% of total plasma protein.

- Half-Life: The protein remains in circulation for roughly 18 to 21 days.

- Calcium Binding: About 40% of serum calcium is bound to albumin, affecting lab interpretation.

The Physiology of Albumin Production and Function

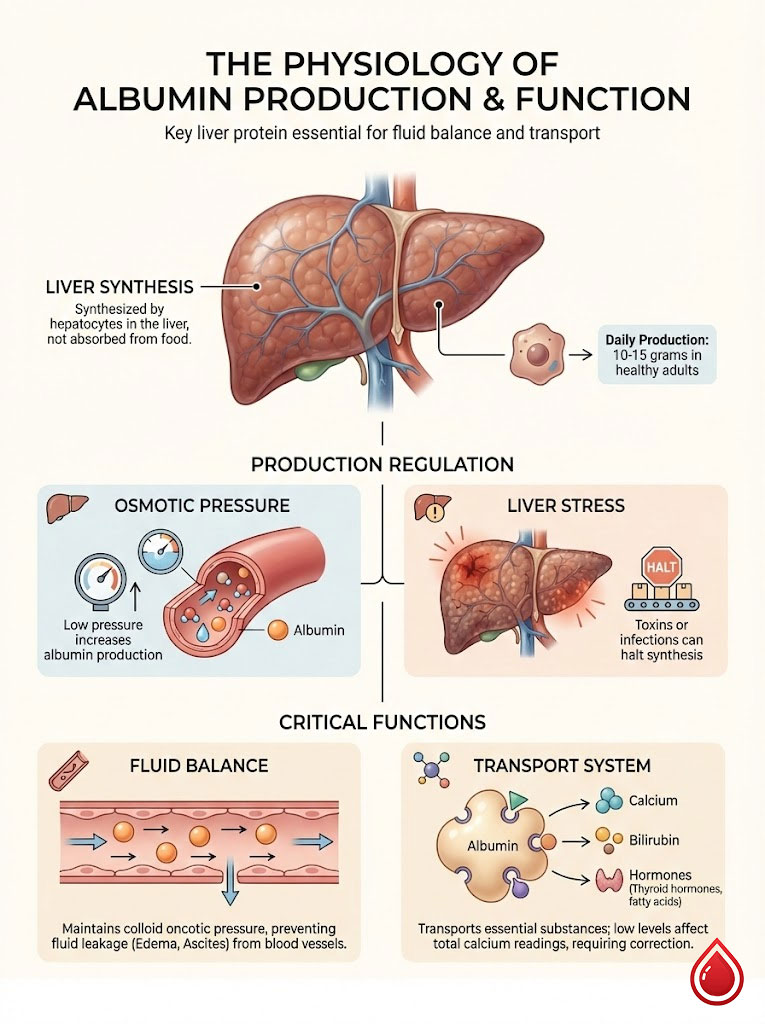

To understand pathology, we must first master physiology. Albumin isn’t absorbed directly from the steak or eggs you eat. It’s synthesized endogenously. This means your body builds it from scratch using amino acids.

The Hepatocyte Assembly Line

The exclusive manufacturing plant for albumin is the liver. Specifically, cells called hepatocytes are responsible for this production. In a healthy adult, these cells work tirelessly. They churn out between 10 to 15 grams of albumin every single day.

This production isn’t static. It’s highly regulated. The body senses changes in osmotic pressure (the concentration of particles in the blood). If pressure drops, healthy hepatocytes ramp up production to compensate.

However, this factory has limits. The body prioritizes immediate survival over long-term maintenance. Any significant stress on the liver can halt the assembly line. This stress could come from toxins, alcohol, or viral infections. When we see hypoalbuminemia, we immediately ask a crucial question.

Is the factory broken? Or is it just on strike?

Understanding Colloid Oncotic Pressure

Think of your blood vessels as a garden hose with tiny, microscopic holes. Water naturally wants to leak out of these holes into the surrounding soil (your body tissues). Albumin acts like a sponge inside the hose.

Because it’s a large molecule that can’t easily pass through the holes, it stays in the bloodstream. It holds onto the water. This force is called colloid oncotic pressure.

When albumin levels drop, you lose that “sponge” effect. The water is no longer held inside the vessels. It begins to seep into the interstitial spaces. This is the physiological mechanism behind edema (swelling) and ascites (fluid in the abdomen). The blood volume effectively decreases, even though the body is retaining water.

The Great Transporter: Ligand Binding

Beyond maintaining pressure, albumin is the blood’s primary taxi service. It possesses a unique structure that allows it to bind with substances that are otherwise insoluble in water. It transports calcium, bilirubin, free fatty acids, and essential hormones like thyroxine.

This transport function is critical for medication management. Many drugs rely on albumin to travel through the bloodstream. We’ll discuss the dangers of this later in the treatment section.

Expert Insight: The Calcium Connection

Approximately 40% of the calcium in your blood travels attached to albumin. If your albumin is low, your total calcium lab result will also appear low. This happens even if your biologically active (ionized) calcium is normal. Before starting calcium supplements, we always use a corrected calcium calculator. This helps us see if the deficiency is real or just an artifact of low albumin.

Interpreting the Numbers: Reference Ranges and Severity

Lab reports can be confusing. “Normal” is a statistical range, not a strict biological switch. However, specific thresholds guide our clinical decision-making.

Standard vs. Optimal Ranges

The generally accepted normal albumin range is 3.4 to 5.4 g/dL (34 to 54 g/L). Values can fluctuate slightly based on hydration status and the specific laboratory’s calibration.

We break down the severity as follows:

- Mild Depletion (3.0 to 3.4 g/dL): Often seen in elderly patients or mild chronic inflammation. This usually doesn’t cause visible symptoms.

- Moderate Depletion (2.5 to 3.0 g/dL): Common in chronic diseases or acute infection. Edema (swelling) may start to appear in the ankles.

- Severe Depletion (Below 2.5 g/dL): This is a critical value. At this level, the loss of oncotic pressure is significant. This leads to severe edema and potential complications with drug metabolism.

The Albumin to Globulin (A/G) Ratio

On your metabolic panel, you’ll often see a calculated value called the A/G ratio. Total protein is composed primarily of albumin and globulin. While albumin keeps fluid in vessels, globulins are immune proteins (antibodies) produced by the immune system.

A low A/G ratio gives us a clue. If the ratio is low because albumin is low but globulin is normal, we suspect production failure or loss. However, consider the alternative.

If the ratio is low because globulin is high, we suspect chronic inflammation. This could point to autoimmune disease or conditions like Multiple Myeloma where the body overproduces immune proteins.

Acute vs. Chronic Declines

The speed of the drop matters immensely. Because albumin has a half-life of roughly 20 days, a sudden drop within 24 to 48 hours is rarely due to nutritional deficiency. It’s also rarely due to liver failure alone.

A rapid drop is almost always due to hemodilution (receiving too many IV fluids). Or it could be an acute inflammatory event (sepsis or trauma). In these cases, blood vessels become “leaky” (capillary permeability). This allows albumin to escape into tissues rapidly.

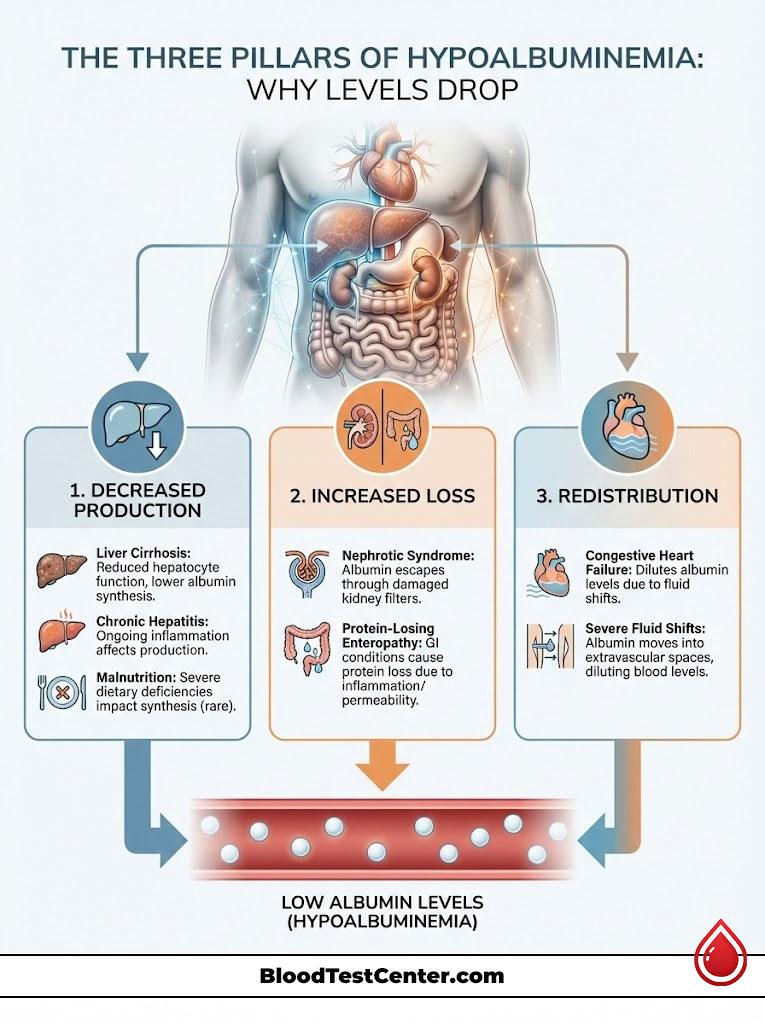

The Three Pillars of Hypoalbuminemia: Why Levels Drop

When investigating what does low albumin in a blood test really mean, we categorize the causes into three distinct buckets. These are decreased production, increased loss, and redistribution.

Mechanism 1: Decreased Production (The Liver)

This is the mechanism most patients fear. Since hepatocytes synthesize the protein, extensive liver damage inevitably leads to hypoalbuminemia.

Liver Cirrhosis and Fibrosis

In end-stage liver disease, healthy tissue is replaced by scar tissue (fibrosis). The number of functioning hepatocytes dwindles. The remaining cells simply can’t keep up with demand.

According to the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), albumin levels are a key prognostic factor. They are used in scoring the severity of cirrhosis (Child-Pugh score). As the liver hardens, albumin drops.

Chronic Hepatitis

Long-term inflammation from Hepatitis B or C can suppress synthesis before cirrhosis even fully develops. The virus creates a constant state of inflammation. This distracts the liver from its protein-building duties.

Malnutrition and Absorption Issues

While rare in the US, a severe lack of dietary protein provides the liver with insufficient amino acids. It lacks the building blocks to build albumin. However, the body is remarkably resilient.

You practically have to be starving for albumin to drop solely due to diet. We see this more often in elderly patients with “tea and toast” diets. We also see it in severe eating disorders.

Mechanism 2: Increased Loss (The Kidneys and Gut)

Sometimes the factory is working perfectly. The problem is that the product is being thrown out the back door.

Renal Loss (Nephrotic Syndrome)

The kidneys act as a filter. The glomerulus (the kidney’s filtering unit) is designed to keep large proteins like albumin in the blood. It lets waste pass into urine. In kidney disease, specifically Nephrotic Syndrome, this filter becomes damaged.

It develops holes large enough for albumin to pass through. This condition is characterized by heavy proteinuria (protein in urine). You will see low blood albumin and significant edema.

Why does this happen? Diabetes is a leading cause. High blood sugar slowly damages the filtration barrier over years. Other causes include autoimmune conditions like Lupus.

Gastrointestinal Loss

The gut can also be a source of loss. In conditions like Protein-Losing Enteropathy (PLE), Crohn’s disease, or Celiac disease, the lining of the gut becomes inflamed. It becomes porous.

Protein leaks from the blood capillaries into the intestinal lumen. It is then lost in the stool. This is often accompanied by diarrhea and weight loss.

Mechanism 3: Hemodilution and Redistribution

This is a “relative” decrease. The total amount of albumin in the body might be normal. But it’s diluted or hiding.

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF)

In CHF, the body retains massive amounts of fluid. This increases blood volume. It dilutes the concentration of albumin.

Third Spacing

In severe burns or pancreatitis, fluid moves from the blood vessels into body cavities (third spaces). It takes albumin with it. The albumin blood test reads low because the protein is hiding in the tissues. It’s not circulating in the veins where we draw the blood.

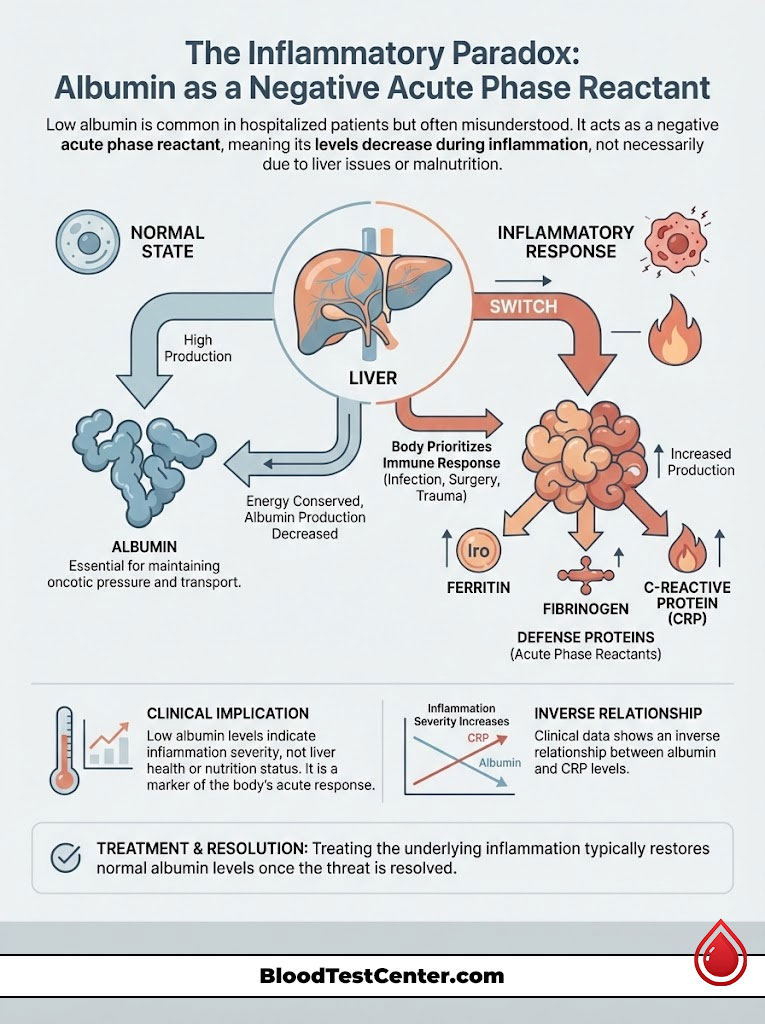

The Inflammatory Paradox: Albumin as a Negative Acute Phase Reactant

The Most Misunderstood Cause

This is the most common reason for low albumin in hospitalized patients. Yet, it is frequently misunderstood by patients and families. Albumin is a negative acute phase reactant.

What does this mean? When the body detects a threat, it shifts into “war mode.” This threat could be a bacterial infection, major surgery, or significant trauma.

The liver receives signals (cytokines like IL-6) to stop making “housekeeping” proteins like albumin. It switches to making “defense” proteins. These include Ferritin, Fibrinogen, and C-Reactive Protein (CRP).

The body intentionally downregulates albumin production. It does this to save energy for the immune response. Therefore, a low albumin level in a sick patient often indicates the severity of the inflammation. It doesn’t necessarily reflect the health of the liver or nutritional status.

The Inverse Relationship with CRP

We observe a distinct seesaw effect in clinical data. As C-Reactive Protein levels spike, albumin levels drop. If I see a patient with an albumin of 2.8 g/dL and a highly elevated CRP, I am less worried about liver failure.

I am more focused on finding the source of the infection or inflammation. Treating the inflammation usually corrects the albumin level automatically. Once the “war” is over, the liver goes back to its normal housekeeping duties.

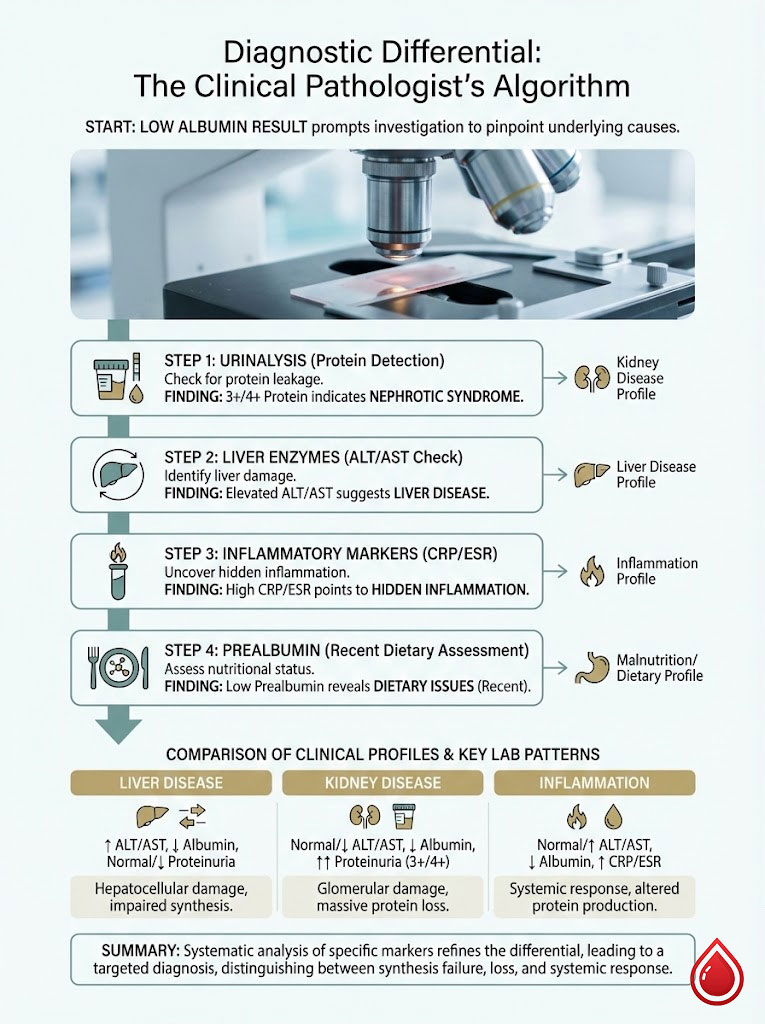

Diagnostic Differential: The Clinical Detective Work

The Clinical Pathologist’s Algorithm

Finding an isolated low albumin result is a call for investigation. We don’t guess. We follow a logical path to pinpoint the source.

Step 1: Check the Urinalysis

We look for protein. If the urine dipstick shows 3+ or 4+ protein, the diagnosis is likely renal (Nephrotic Syndrome). We then order a quantitative test called a Urine Protein to Creatinine Ratio.

Step 2: Check Liver Enzymes (ALT/AST)

If the urine is clean, we look at the liver. If ALT and AST are elevated, or if bilirubin is high, we suspect hepatocellular damage. This points toward Liver Disease. We may order an ultrasound or specific viral hepatitis panels.

Step 3: Check Inflammatory Markers (CRP/ESR)

If both the liver and kidneys look fine, we check for hidden inflammation. If CRP and ESR are high, the low albumin is likely secondary to inflammation. We then hunt for the infection or autoimmune flare.

Step 4: Check Prealbumin

If we suspect recent dietary issues, we check prealbumin. This gives us a better real-time snapshot of nutritional intake.

Comparison of Clinical Profiles

Distinguishing between the causes requires looking at the whole picture. Here is how we differentiate the three major culprits based on lab patterns:

| Clinical Feature | Liver Disease (Cirrhosis) | Kidney Disease (Nephrotic Syndrome) | Acute Inflammation/Sepsis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin Level | Low (Chronic decline) | Low (Often severe) | Low (Rapid drop) |

| Urine Protein | Negative or Trace | 4+ Positive (Heavy) | Negative |

| Liver Enzymes | Elevated (ALT/AST) | Normal | Variable |

| Edema | Ascites (Abdomen) | Generalized (Face/Legs) | Generalized |

| CRP Level | Variable | Normal | Markedly Elevated |

| Primary Mechanism | Synthesis Failure | Filtration Loss | Downregulation/Leakage |

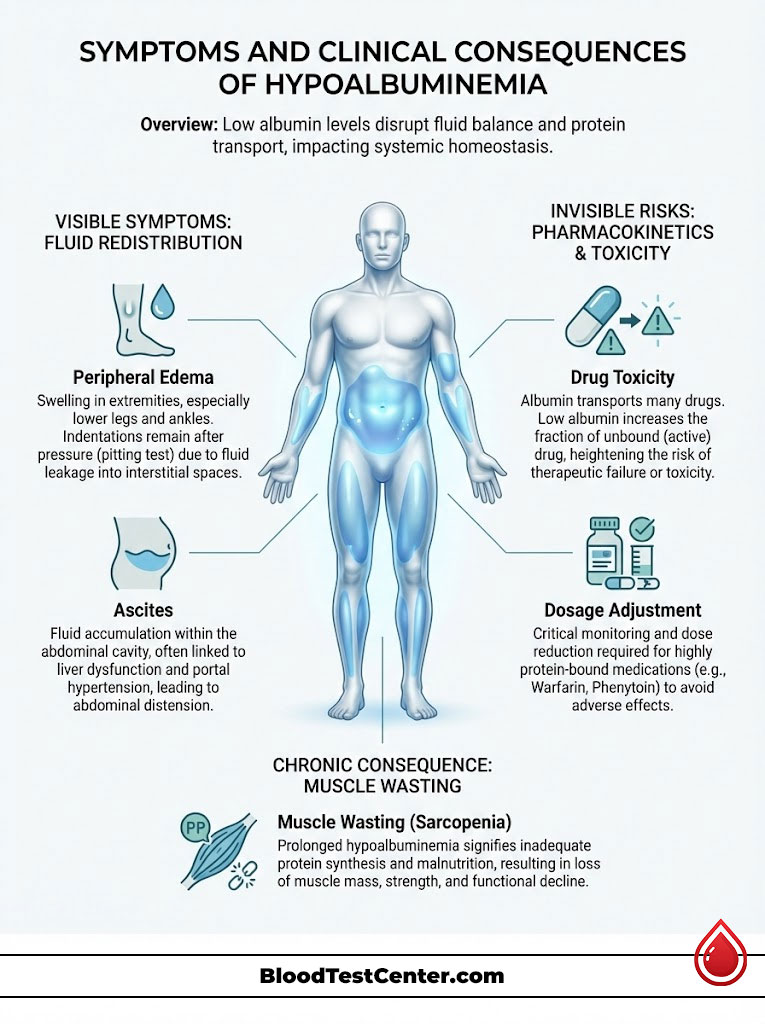

Symptoms and Clinical Consequences

When albumin drops, the body struggles to maintain homeostasis. The symptoms can be subtle at first. Eventually, they become impossible to ignore.

Visible Symptoms: The Fluid Problem

The most obvious physical manifestation of hypoalbuminemia is fluid redistribution. It’s simply physics in action.

Peripheral Edema is the most common sign. This usually appears as pitting edema in the lower extremities. If you press your thumb into the skin of the ankle and the indentation remains for a few seconds, that is pitting edema. It happens because gravity pulls the water down. There isn’t enough albumin to hold it in the veins against that gravitational pull.

Ascites is another major symptom, specifically in liver disease. Fluid accumulates in the peritoneal cavity (the abdomen). This causes significant distension. This is driven by a combination of low albumin and high pressure in the portal vein (portal hypertension).

Muscle Wasting is also prevalent. Chronic low albumin often correlates with a catabolic state. The body breaks down muscle for energy. This leads to weakness and fatigue.

Invisible Risks: Pharmacokinetics and Drug Toxicity

Here is a detail that pharmacy experts stress but general articles often miss. Many drugs are “protein-bound.” They travel through the blood attached to albumin. Only the “free” portion of the drug is active.

Think of albumin as a bus and the drug molecules as passengers. If there are plenty of buses (albumin), most passengers are seated and safe. If there are fewer buses, more passengers are left wandering the streets (free drug).

If you take a drug like Warfarin (a blood thinner) or Phenytoin (seizure medication), the dosage is calculated based on normal albumin levels. If your albumin drops, there are fewer binding sites. The result? More “free” drug circulates in the system.

This can lead to drug toxicity even if you are taking the standard dose. For patients on blood thinners, hypoalbuminemia increases the risk of bleeding events significantly. This necessitates closer monitoring. It may potentially require lower drug dosages.

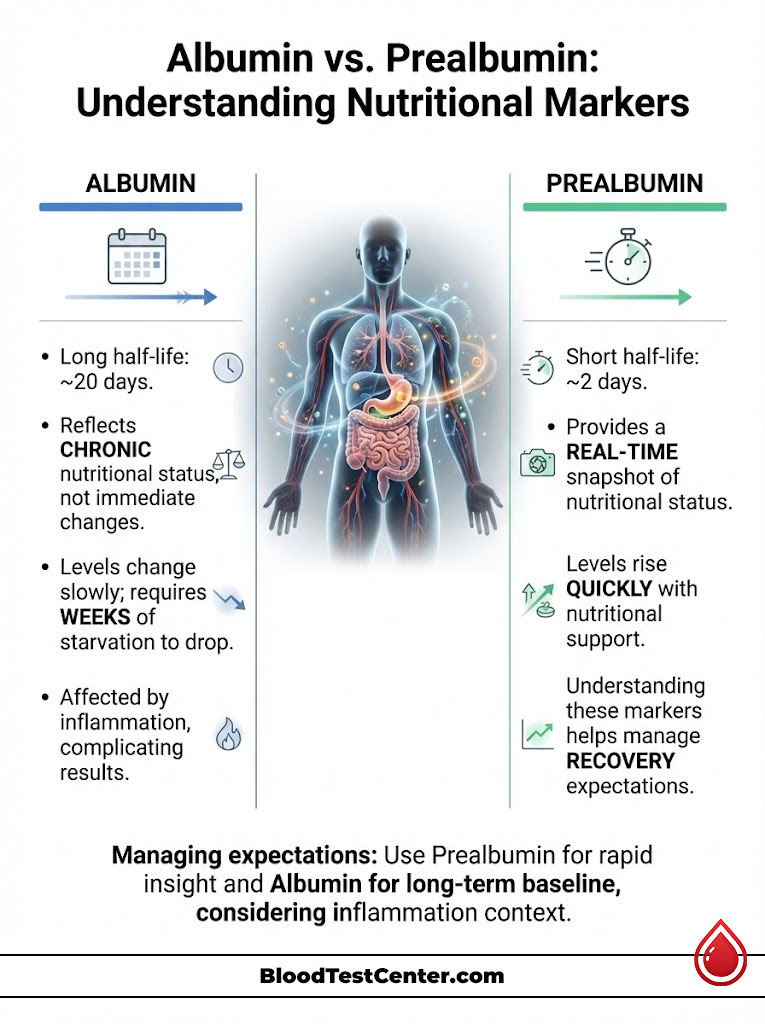

Albumin vs. Prealbumin: Understanding Nutritional Markers

Why Prealbumin Might Be Better for Nutrition

For years, doctors used albumin as a marker for malnutrition. We now know this is flawed. Because albumin has a half-life of 20 days and a massive body pool, it takes weeks of starvation for levels to drop.

Conversely, it takes weeks of good nutrition to bring them back up. It’s like trying to steer a cruise ship. It turns slowly.

For a real-time snapshot of nutritional status, we prefer Prealbumin (Transthyretin). It has a half-life of only 2 days. If we start a patient on nutritional support, prealbumin will rise within days. This tells us if our intervention is working long before albumin budges.

Comparison of Biomarkers

Understanding the difference between these two tests helps manage expectations regarding recovery time.

| Feature | Serum Albumin | Prealbumin (Transthyretin) |

|---|---|---|

| Half-Life | ~20 Days (Long-term view) | ~2 Days (Snapshot view) |

| Primary Use | Chronic illness, Liver/Kidney health | Acute nutritional assessment |

| Pool Size | Large body pool | Small body pool |

| Sensitivity to Diet | Slow to change | Changes rapidly with feeding |

| Affected by Inflammation? | Yes (Negative Acute Phase) | Yes (Negative Acute Phase) |

Practical Strategies and Management

When is Dietary Intervention Sufficient?

If the cause of low albumin is purely nutritional, increasing dietary protein is the solution. This is rare outside of severe eating disorders or neglect. However, it is common in the elderly.

We focus on high biological value proteins. These are proteins that contain all essential amino acids and are easily absorbed. Egg whites, whey protein, and lean meats are the gold standard.

However, there is a catch. If the gut is inflamed (malabsorption), simply eating more protein won’t help. The gut must be healed first. In cases like Crohn’s disease, we may need to treat the inflammation with steroids before the diet can work.

Medical Management: Treating the Disease, Not the Number

Treating the number is rarely the goal. We must treat the disease process causing the number to drop.

Diuretics for Symptom Control

To manage the symptoms of low albumin like edema, doctors often prescribe diuretics (water pills). Furosemide (Lasix) is a common choice. This helps the kidneys remove excess fluid that has leaked into tissues.

The Controversy of IV Albumin Infusions

You might wonder, “Why not just inject albumin?” It seems like a logical fix. We do use it, but only in specific scenarios.

IV albumin is expensive. More importantly, the effect is transient. Because the underlying issue (like a leaky kidney) persists, the infused albumin often leaks out or is metabolized within 24 hours.

It is reserved for specific conditions. We use it for hepatorenal syndrome. We use it after large-volume paracentesis (draining fluid from the abdomen) to prevent circulatory collapse. We rarely use it just to “fix” a low lab value.

Root Cause Resolution

If the cause is Nephrotic Syndrome, steroids or immunosuppressants are needed. These drugs stop the immune system from attacking the kidney filter. If it is inflammation from an infection, antibiotics are the priority. Once the infection clears, the albumin corrects itself.

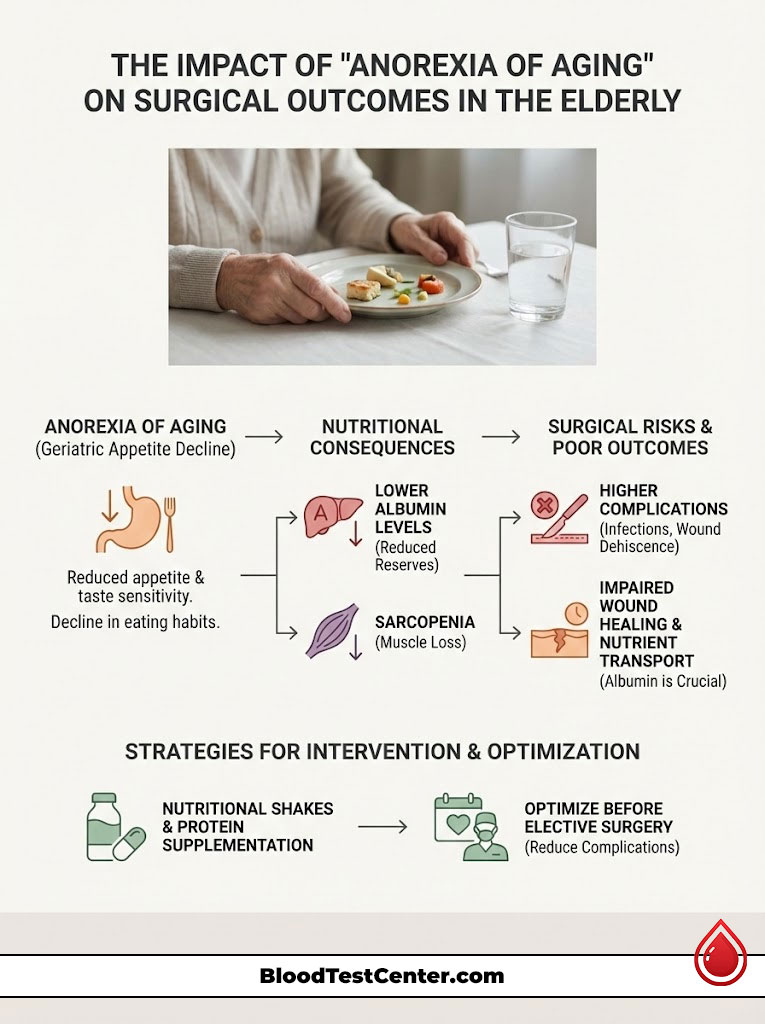

Special Populations: The Elderly and Surgical Patients

The “Anorexia of Aging”

In geriatric medicine, we see a slow, creeping decline in albumin. This is often due to a condition called “anorexia of aging.” Older adults often lose their taste sensitivity.

They eat less meat because of chewing difficulties. They rely on carbohydrates. This leads to sarcopenia (muscle loss) and lower albumin reserves. For these patients, nutritional shakes and protein supplementation can make a massive difference in quality of life.

Surgical Outcomes

Surgeons obsess over albumin levels. Why? Because albumin is essential for wound healing. It transports the necessary nutrients to the surgical site.

Data shows that patients with low preoperative albumin have higher rates of complications. They have more surgical site infections. They have higher rates of wound dehiscence (the wound popping open).

If a surgery is elective, we often delay it. We spend weeks optimizing the patient’s nutrition to get their albumin up. This significantly lowers the risk of complications.

Summary & Key Takeaways

Albumin is far more than a simple nutritional marker. It is a complex protein that reflects the balance between synthesis in the liver, filtration in the kidneys, and the body’s inflammatory state.

So, what does low albumin in a blood test really mean? It means the body’s homeostasis is disrupted.

An isolated low albumin result is a call for investigation. It requires a look at the liver, the kidneys, and the body’s inflammatory state to uncover the true clinical picture. It is a symptom, not a diagnosis.

Whether it stems from the reduced production of cirrhosis, the filtration loss of nephrotic syndrome, or the suppression of an acute infection, understanding the “why” is the only way to effectively manage the “what.”

If your levels are low, talk to your doctor about the three pillars: Production, Loss, and Inflammation. Ask for the follow-up tests mentioned here. By pinpointing the mechanism, you can target the treatment and restore balance to your body.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary function of albumin in the human body?

Albumin is the most abundant plasma protein and is essential for maintaining colloid oncotic pressure, which keeps fluid inside blood vessels. It also functions as a vital transport molecule, carrying hormones, fatty acids, and various medications through the bloodstream to their target tissues.

What is the standard reference range for serum albumin, and when is it considered critical?

A normal albumin level typically ranges from 3.4 to 5.4 g/dL. Clinical concern increases when levels drop below 3.0 g/dL, and levels below 2.0 g/dL are considered critical as they are statistically associated with significantly higher mortality rates in hospitalized patients.

How does liver disease specifically cause low albumin levels?

The liver’s hepatocytes are the body’s exclusive manufacturing plant for albumin, synthesizing 10 to 15 grams daily. In conditions like cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis, healthy liver tissue is replaced by fibrosis, which impairs the organ’s functional capacity to produce this vital protein.

What is the relationship between kidney disease and hypoalbuminemia?

In kidney disorders such as Nephrotic Syndrome, the filtration barrier in the glomerulus becomes damaged and porous. This allows large albumin molecules to leak into the urine (proteinuria), depleting the body’s circulating supply even if the liver is producing the protein at a normal rate.

Why does low albumin cause swelling or edema in the legs and abdomen?

Without sufficient albumin to provide “oncotic pressure,” the blood loses its “sponge-like” ability to hold water within the vascular system. This fluid then leaks into the interstitial spaces, resulting in peripheral pitting edema in the limbs or ascites in the abdominal cavity.

Why do albumin levels often drop during an acute infection or after surgery?

Albumin is a “negative acute phase reactant,” meaning the liver downregulates its production during systemic inflammation. This shift allows the body to prioritize the synthesis of defense proteins, such as C-Reactive Protein (CRP), to manage the immediate threat of infection or trauma.

Can you fix low albumin simply by eating more protein?

Increasing protein intake only corrects hypoalbuminemia if the root cause is pure nutritional deficiency or “anorexia of aging.” If the low level is caused by kidney loss, liver failure, or chronic inflammation, the underlying medical condition must be treated before albumin levels will normalize.

What is the difference between an albumin test and a prealbumin test for monitoring nutrition?

Albumin has a long half-life of about 20 days, making it a better indicator of long-term health trends rather than immediate nutritional changes. Prealbumin has a half-life of only 2 days, providing clinicians with a “real-time” snapshot of whether a patient’s current nutritional support is effective.

How does low albumin affect the way medications work in the body?

Many drugs are “protein-bound,” meaning they travel through the blood attached to albumin. When albumin is low, there are fewer binding sites, leading to higher concentrations of “free” active drug in the system, which can cause drug toxicity even at standard dosages.

Why does low albumin lead to a false low calcium reading on a blood test?

Since approximately 40% of serum calcium is bound to albumin, a drop in protein levels will cause the “total calcium” measurement on a lab report to appear low. Clinicians must use a corrected calcium formula to determine if the biologically active, ionized calcium is actually at a safe level.

What does a low Albumin to Globulin (A/G) ratio indicate on a lab report?

A low A/G ratio suggests either a decrease in albumin (due to liver or kidney issues) or an overproduction of globulins (due to autoimmune disease or multiple myeloma). This ratio serves as a diagnostic clue to help differentiate between production failure and an overactive immune response.

Can IV albumin infusions be used to permanently correct low serum levels?

IV albumin is typically reserved for acute clinical scenarios, such as large-volume paracentesis, because its effects are very transient. Unless the underlying disease causing the loss or production failure is resolved, the infused albumin will be metabolized or leak out of the vessels within 24 hours.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Hypoalbuminemia is a complex clinical finding that requires professional evaluation. Always consult with a qualified healthcare provider to interpret your laboratory results and develop a personalized treatment plan based on your specific medical history.

References

- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) – aasld.org – Guidelines on the management of cirrhosis and the prognostic significance of serum albumin levels.

- National Kidney Foundation – kidney.org – Clinical resources on Nephrotic Syndrome, proteinuria, and the impact of kidney disease on serum protein levels.

- Journal of Clinical Pathology – jcp.bmj.com – Research papers regarding albumin as a negative acute phase reactant during systemic inflammation.

- Merck Manual Professional Version – merckmanuals.com – Detailed clinical breakdown of the pathophysiology of hypoalbuminemia and colloid oncotic pressure.

- Mayo Clinic Laboratories – mayocliniclabs.com – Reference ranges and clinical interpretation for Serum Albumin and the Albumin/Globulin (A/G) ratio.

- American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (ASPEN) – nutritioncare.org – Position papers on the use of prealbumin vs. albumin as markers for nutritional status.

- PubMed / National Library of Medicine – nlm.nih.gov – Studies on the pharmacokinetics of protein-bound drugs and the risk of toxicity in hypoalbuminemic patients.